Andrew Gelman has turned his eagle-eyed research on the American voter into an excellent book, Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State. (The book’s website is here). If you ever doubted the value of empirical research, this book will change your mind. It’s full of novel, data-driven results.

The most notable: The income-party link is strongest in poor states, and almost disappears in the richest. Race does not fully account for this pattern:

Perhaps the high slope in Mississippi reflects poor black Democrats and rich white Republicans, with Connecticut’s flatter slope being the result of its more racially homogeneous population… When we did this, we got the same pattern as before, but a bit weaker. About half of the difference in the income-voting patter between Mississippi and Connecticut goes away when we consider only whites.

Originality aside, Gelman’s book is very well written, thoughtful, and statistically transparent – and the cover is so good that my five-year-olds wanted me to make it their bedtime story. He deserves to sell a lot of copies.

With a piece of scholarship this careful, the main sticking point is bound to be interpretation. While many of Gelman’s points hit home, my write-up of his results would have been fairly different.

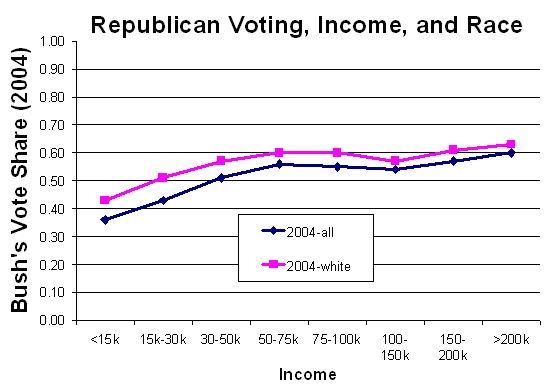

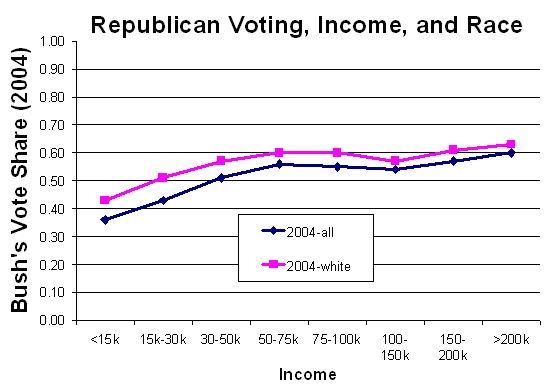

For starters: Gelman repeatedly emphasizes that, contrary to naive politicos, rich people (but not rich states!) are still a lot more Republican than poor people: “at the individual level, income continues to be an important predictor of Republican vote.” Elsewhere in the book, he’s careful to admit that income is partly a proxy for race. He was even nice enough to give me his data for all voters versus white voters. But frankly, when I look at a graph I constructed using his data, the income-vote connection doesn’t look “important” to me. Adjusting for race, the income-vote connection is barely worth mentioning:

Look at the 2004 white vote. If you ignore Americans earning less than $30k a year, Republican voting as a function of income looks virtually flat to me. Do my eyes deceive me? Among whites, $30-50k earners are no less likely to vote Republican than $100-150k earners; you can quintuple income without changing a thing! The appearance of a pattern largely depends on the 8% of respondents earning under $15k – and the 3% earning over $200k.

Now Gelman could fairly respond, “But I show that within states, the effect is often larger.” But then I’d say:

Then your real message isn’t that “Income is important.” Instead, your real message is that “Income is important adjusting for state culture.” Or even “In poor states, income is important adjusting for state culture.” You sound a lot more like Thomas Frank than you’d like to admit.

Perhaps most of my objections to Gelman’s interpretations stem from our disciplinary differences. As an economist, I was raised to expect virtually all poor people to be Democrats, and virtually all rich people to be Republicans. From this starting point, Gelman’s data show that income is practically irrelevant. But perhaps as a political scientist, Gelman is used to hearing that income doesn’t matter at all. From this starting point, Gelman can fairly object that income definitely matters in specific circumstances.

I’ll blog more details from Gelman’s book in coming weeks. But my overall view is that, contrary to much of the book’s marketing, Gelman rarely refutes other analysts’ claims about the American voter. Instead, he highlights patterns that no one else is talking about. That’s why almost everyone can learn from Gelman’s great book. Don’t miss it.

READER COMMENTS

Troy Camplin, Ph.D.

Aug 4 2008 at 9:18pm

Looks to me that once you get past about $40K, income does not affect which party you vote for, but below that, it does. MIght explain why Democrats tend to support social programs which in design (if not explicit intention) keep the poor poor.

Jim

Aug 5 2008 at 3:45am

If you ignore Americans earning less than $30k a year

Why would you do that? Unless you’re a Republican, I mean.

And even when you do, there’s still a >10 percentage point difference in Bush’s vote share between the lower and upper end of your income scale. I’m not sure why you call this ‘practically irrelevant’, unless it doesn’t look significant to you because you’re used to looking at charts with axes that don’t begin at zero. In which case yes, your eyes deceive you.

floccina

Aug 5 2008 at 9:32am

I say it goes even further than race. WASPs are more likely to vote Republican. Some very conservative non WASP vote democrat and would not consider voting Republican. IMO that is why some Democrats at the local level are very conservative.

Steve Sailer

Aug 5 2008 at 10:05pm

What really drives states into the red or blue columns is affordable family formation. Inland states where there is a huge supply of land for suburban expansion have lower home prices, so white people get married younger and have more children. Having a family makes them open to Republican family value appeals.

The correlations between voting by state and white rates of being married and having children are among the highest in the history of the social sciences. For documentation, see my American Conservative article:

http://www.amconmag.com/2008/2008_02_11/article.html

Comments are closed.