Part of the reason money growth predicts real economic growth is because banks are in the business of being ahead of the curve: They lend money when they think a boom is likely in the near future, and they cut back on lending when they think the future looks grim. The relationship is pretty strong in real life:

…inside [bank created] money is more tightly linked to output than is the money distributed by the Federal Reserve.

So to some extent money growth is probably predicting the boom rather than causing the boom. Is the same thing going on with fiscal policy? Do governments find it easier and more appealing to borrow and spend when a boom is just around the corner? What would it look like if government spending predicted economic recovery rather than causing it?

It would look like this:

This is from a toy economy I created, a dramatically simplified version of the classic regime-switching model of Hamilton (

PDF). In this economy, times are either “good” (economy grows about 1.2% this quarter) or “bad” (shrinks about 0.4% this quarter). Good quarters are very likely to follow each other (90% chance) while bad quarters aren’t quite as likely to persist (75% chance). Government spending has no influence on GDP in this fake economy: This is a supply-side, real business cycle economy. I add a bit of noise to the data to make it about as volatile as the actual U.S. experience. Here are 125 years of fake GDP data in this economy:

There are 32 recessions in these 125 computer-simulated years, which coincidentally is the

same number of recessions the U.S. has experienced since 1854.

Here’s where the rabbit goes in the hat: I take the GDP figures as given and just

assume that government spending rises by 1% of GDP in the quarter before the economy switches from the bad state back to the good state. Maybe it’s for Machiavellian

credit-claiming reasons, maybe it’s because the credit markets or CBO say it’s safe to borrow, the reason doesn’t matter. Government spending goes from 15% of GDP up to 16% and then goes back to 15% the next quarter.

And notice: Since that “1%” stimulus only lasts a quarter, it really costs 0.25% of GDP since we report GDP at annual rates.

The next step was to run the kind of statistical analysis on my

fake data that macroeconomists typically do with

real data: I ran a simple Vector Autoregression, the tool that Christopher Sims won the Nobel for improving, the tool that is

routinely used to estimate government spending multipliers.

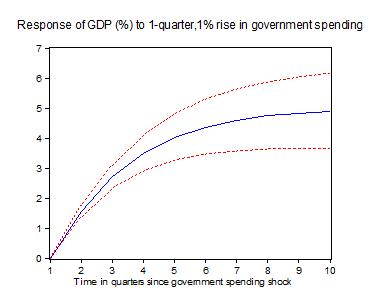

I asked my software package a simple question: If you look at the historical relationship between government spending and GDP, what happens to GDP over the next 10 quarters whenever government spending rises by 1%? The first graph above gives the answer to that question:

After a fiscal stimulus, GDP rises, it rises a lot, and it stays high for a long, long time.

You can see that after a burst of government spending, GDP is about 4% higher than usual for over two years. Since you and I know that’s just because the government hired in anticipation of the coming boom, we aren’t going to be fooled into thinking that government spending caused the growth. But if you handed these data to a conventional economist and asked them to estimate the government spending multiplier, she’d tell you that of course “correlation isn’t causation,” but all the same she’d find a government spending multiplier of 35.

Why is the multiplier so high? Because in this economy (and probably in actual U.S. experience) periods of decent growth last a reasonably long time, so if governments are good at spending a lot of money right before the switch to rapid GDP growth the multiplier will look huge.

Think of the campaign ads: The economy was collapsing, then there was a government hiring wave (or maybe a tax cut!), and then the economy went back to decent, long-lasting growth. The politicians don’t have to get everyone to believe the stimulus caused the boom, but every vote helps.

35 is far too high a multiplier, unbelievable. But every step toward making this toy model a bit more realistic will pull the multiplier down to realistic values:

Does the government spend for a year before the boom rather than a quarter? That cuts it by a factor of 4.

Does the government only correctly guess the boom’s timing half the time? Cut the multiplier perhaps in half.

Does the government spend 2% of GDP instead of 1%? Half again.

Now we’re down to the socially acceptable spending multipliers of about 2.

Don’t get me wrong: I think loose government monetary policy and loose government fiscal policy both usually boost GDP in the short run

at least modestly. But just as serious people worry about whether banks might lend into booms that were in the pipeline anyway, serious people should worry about whether governments are doing the same.

READER COMMENTS

Charley Hooper

Feb 20 2013 at 5:39pm

This is interesting and makes sense to me. However, it might not need any forward thinking (e.g., anticipation of a boom) on the part of the government. It might be purely accidental.

If the government doesn’t notice a recession right away and it takes another amount of time to mount a fiscal attack, then the fiscal stimulus might happen right before the recovery. And the economy will recover, as we are assuming, but it would have recovered even without the stimulus. Of course, we mathematical types will later say that, yes, the stimulus helped, not from a cause and effect proof, but from the theoretical reason that it should have helped and the timing was such that it looks like it helped.

Mark V Anderson

Feb 20 2013 at 8:37pm

But this all rests on the assumption that government spending generally rises just before the economy is going to go up anyway. You’ve made an interesting thought balloon about why calculated multipliers could be way out of whack, but do you have any evidence?

Chris (Robotbeat)

Feb 20 2013 at 10:46pm

How does the gov’t predict the market is going to improve before the market does? I know you answer this question with some possibilities, but it undermines the assumption of an efficient market, upon which the remainder of your argument rests.

Another, more pertinent question: This is a toy model you made. If somehow you had slightly different assumptions that lead to the opposite result, would you still have posted this?

Joshua Wojnilower

Feb 22 2013 at 5:32am

You mention that inside money both predicts and causes the boom to some degree. Assuming that’s true, which I believe it is, wouldn’t any fiscal multiplier rest in part on the degree to which it encourages an expansion of inside money? Presumably this could come from either the supply side (shoring up bank capital) or demand side (repairing household and nonfinancial corporate balance sheets).

My claim would be that fiscal policy has only had a moderate effect, to date, because it focused largely on the supply side and ignored the demand side (as outlined above).

8

Feb 25 2013 at 5:25am

They lend money when they think a boom is likely in the near future, and they cut back on lending when they think the future looks grim.

Banks constrain lending during booms (to the extent they do at all).They are constrained by borrowers today. When borrowers are optimistic, the demand for credit is great, when borrowers are pessimistic, even near 0% rates cannot entice them.

But just as serious people worry about whether banks might lend into booms that were in the pipeline anyway, serious people should worry about whether governments are doing the same.

Governments always act too late and their actions have greater impact because they are pro-cyclical. Guess when the government will decide that we need inflation at all costs?

Major_Freedom

Mar 1 2013 at 9:17am

Mark V Anderson:

“But this all rests on the assumption that government spending generally rises just before the economy is going to go up anyway.”

But that is what Keynesian theory predicts, Mark. Keynesians also believe that the data is consistent with this prediction. It isn’t an “assumption” made by Jones. He’s just taking a “conventional wisdom” and flipping it on its head.

Comments are closed.