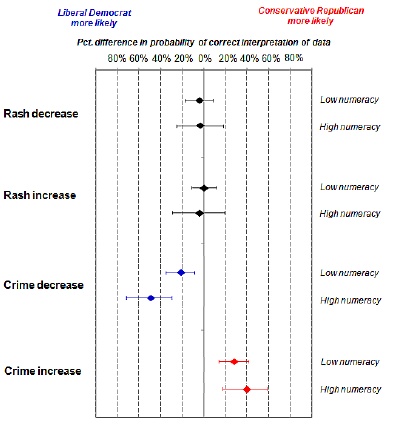

Kevin Drum and Chris Mooney have already posted excellent summaries of this neat study of motivated numeracy. You should read them. But if you prefer the digest version: Even unusually numerate people take off their thinking caps when the numbers are ideologically inconvenient. Here’s another neat graph from the original paper:

On the non-ideological question about the effect of ointment on a rash, ideology has no effect on accuracy, holding objective numeracy fixed. On the ideological question about the effective of gun control on crime, however, ideology has a big effect – and the effect rises with numeracy.

What does it all mean? Mooney calls the results “Enlightenment destroying”:

The Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume

famously described reason as a “slave of the passions.” Today’s

political scientists and political psychologists, like Kahan, are now

affirming Hume’s statement with reams of new data.

But this is a gross misinterpretation of what the Enlightenment was all about. The Enlightenment claim was never, “Everyone is already reasonable.” Voltaire himself lamented that, “Common sense is not so common.” The Enlightenment claim, rather, was “Most people aren’t reasonable – and the evils of the world are part, the predictable consequence of their irrationality.” The evidence on motivated numeracy doesn’t justify fatalism. It should instead inspire commitment to epistemic Puritanism – an ethic of intellectual self-control, dispassion, and disdain for groupthink.

READER COMMENTS

Pat

Sep 6 2013 at 3:51pm

Could it be that people don’t trust their math and go with their assumptions when they have them?

It might not be politically motivated – would be curious to see an example. Perhaps some baseball stat comparison of Bob Eucker and Babe Ruth. The numbers might say that Eucker is better on that stat but people will ignore it because they know deep down that Ruth was better.

Taeyoung

Sep 6 2013 at 4:08pm

Possibly the best support for promoting political diversity in the social sciences that I have ever seen.

Brian

Sep 6 2013 at 4:24pm

“The evidence on motivated numeracy doesn’t justify fatalism. It should instead inspire commitment to epistemic Puritanism – an ethic of intellectual self-control, dispassion, and disdain for groupthink.”

This conclusion is not justified based on the study. The supported cognitive theory in the study, Identity-protective Cognition Thesis (ICT), was applied in a political sense in the paper, but likely applies to people’s self-identity more generally. That is, one need not assume a group-based identity for the effect to hold. Consequently, those who reject groupthink but espouse “me-think” could be just as likely not to follow correct mathematical reasoning.

Moreover, the authors point out that the faulty conclusions may not actually be irrational, but rather a consequence of subjects rationally choosing the advantages of self-identity over lesser advantages of truth. It’s not clear that “epistemic Puritanism” provides an antidote to this effect, since EP can easily become part of one’s self-identity.

Brian

Sep 6 2013 at 4:30pm

Taeyoung,

Yes, but not just in the social sciences. The study suggests that maintaining identity diversity is vital for ensuring that, in any field, all evidence is considered and correctly analyzed.

Tom West

Sep 6 2013 at 4:59pm

Of course, if we’re suggesting policy for society, then aren’t we negatively impacting over-all welfare if we fail to cater to majority’s groupthink?

Is the goal of society truth or human happiness?

Taeyoung

Sep 6 2013 at 4:59pm

Re: Brian

Oh to be sure! But social sciences are most likely to implicate these particular kinds of ideological commitments. Other fields may suffer from crippling groupthink, but not so easily diagnosed, nor so easily corrected.

Various

Sep 6 2013 at 5:58pm

You might be commingling the meanings of the French and Scottish Enlightenments. The former says we humans can use our superior reasoning skills to solve most problems if we just get the right group of brainiacs in one room and then analyze the problems in sufficient detail. The Scottish Enlightenment theorizes that using logic and reason are terrific in concept, but as a practical matter our brains have significant limitations, including our tendency to be corrupted by our passions and biases. Rather, the Scottish Enlightenment postulates that it is better to simply do what works, as determined through evidence and experience.

Rob

Sep 7 2013 at 8:30am

There is no such thing as “the goal of society”.

Tom West

Sep 7 2013 at 9:25am

There is no such thing as “the goal of society”.

Well, in any society, rulers have a reason in mind when they make laws. I think that qualifies as “goals”.

Rob

Sep 7 2013 at 10:24am

I think it qualifies as “reasons for individuals in a given situation to write certain laws”.

I don’t think it qualifies as “the goal of society”. This language misuse implies a form of coherence of volition that was never there and may never be there. Hell, we don’t even know whether the lawmakers thought in goal-oriented ways rather than vague mood and in-group associations.

And obviously, countless laws have been written that negatively affect the goals of people who disagree with these laws.

Kevin

Sep 7 2013 at 12:27pm

Wouldn’t that make the goal of society to get existing incumbents re-elected regardless of either truth or happiness, then?

Chris Koresko

Sep 7 2013 at 4:50pm

Kahan et al.: Will aggressive public spending limit the duration and severity of an economic recession—or compound them? Intense and often rancorous conflict on these issues persists despite the availability of compelling and widely accessible empirical evidence (Kahan 2010).

I wonder which side of the issue they come down on, and on what evidence they base the belief that the issue is settled.

Joseph Hertzlinger

Sep 7 2013 at 7:59pm

Step 1. Researchers give subjects deliberately misleading data.

Step 2. The subjects recognize the data as misleading and ignore it.

Step 3. The researchers cite this as evidence of irrationality.

It looks like cognitive scientists have defined rationality to mean “agrees with us.”

Tom West

Sep 8 2013 at 11:44am

Wouldn’t that make the goal of society to get existing incumbents re-elected regardless of either truth or happiness, then?

How many people of your friends in business are motivated by making the most possible money without any regard for customers, society, family, pride in doing a good job, etc.? How many would lie, cheat, steal or worse, if they knew they could get away with it?

Damn few, right?

Then why assume that those who are in government are any different?

I really don’t understand the “Well, yes, I and everybody I know are pretty decent people, but everyone I don’t know is an absolute mercenary, and borderline sociopath intent on extracting maximum possible gain at any possible cost.”

Simple first order observation proves this wrong.

Tracy W

Sep 8 2013 at 12:28pm

I’m with Joseph. The paper says the data the experimenters provided was manipulated by them to give the results they wanted, apparently in both cases (page 10 of the pdf). It’s rather arrogant of the experimenters to lie to their subjects and then assert that their subjects are innumerate or irrational for not believing their lies.

And particularly so given the long history of psychologists lying to their experimental subjects then boasting about it in their papers and textbooks.

Rob

Sep 8 2013 at 2:09pm

@Tom West

For the record, I don’t consider everybody I know to be pretty decent people, nor the majority of people I communicate with on the internet, or the people I work with or for…

I guess it depends on your standard of what a pretty decent person is, but honestly I don’t trust most people very much, and that’s fully based on observable evidence.

Tom West

Sep 8 2013 at 4:01pm

Oh. You have my sympathies.

Rob

Sep 9 2013 at 8:47am

Heh. I just imagined Bernie Madoff’s or Enron’s victims saying something similar before their finances came crashing down on them.

Of course, you are also probably aware of the Milgram experiments, and the fact that there’s no reason to assume the average participant wouldn’t have tortured you personally, had you been on the receiving end of an actual experiment of that sort.

Untrustworthiness is not just a problem with the state, obviously, but let’s not forget that these are the people who can seize your property, or physically kick down your door and drag you to a room with iron bars you can’t leave, while no one is allowed to organize physical resistance against them.

Tom West

Sep 11 2013 at 12:23am

Of course, trust has its possible costs. And I’m certainly aware of the Milgram, the “banality of evil”, etc. But I’m also aware of the behavior of the people around me, and that’s a powerful counter to the evil I read about. I’m constantly amazed by the lengths people around me go to do good for strangers.

But honestly, I cannot imagine a world more miserable than one in which I felt that I couldn’t trust the vast majority of humanity.

Obviously, the importance of trusting one’s fellow humans is not as important to your happiness, and thank goodness for that.

Comments are closed.