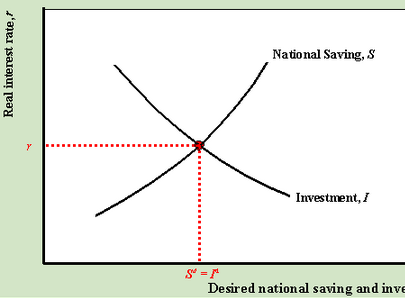

No matter how hard I try, I can’t stop economists from reasoning from price changes. Now I’m seeing more and more economists claiming that at low interest rates we should do more public investment. In fact, there is no necessary correlation between the level of interest rates and the optimal level of investment, public or private. To see why, consider the past two recessions:

1. In 2007-08 there was a drop in household formation, and also tighter lending standards. These events led to a huge drop in housing construction. Housing construction involves a mix of private investment (houses, shopping centers, etc.) and public investment (new local roads, sewer lines, schools, expressways, etc.) When the housing sector booms, the investment schedule shifts to the right, causing an increase in both interest rates and the optimal amount of investment. But in 2008 the schedule shifted left, causing a fall in both interest rates and the optimal quantity of investment (public and private.) State and local governments issued fewer bonds to support urban expansion, as was appropriate. Now of course there was also bad monetary policy in late 2008, which caused non-housing investment to also plunge.

2. In contrast, the 2001 recession was concentrated in the business investment sector. As business investment plunged due to previous overinvestment in tech, interest rates fell, which led to more investment in real estate (public and private.) Again, those changes were entirely appropriate.

Economists tend to make two mistakes in this area. First, they reason from a price change. They forget that lower interest rates don’t call for more investment. It entirely depends on why interest rates change. Does the supply of saving shift right (more investment) or does the investment schedule shift left (less investment.) The second mistake is to forget that public investment is often motivated by quite similar factors to private investment. The same forces that shift the optimal amount of one type of investment, often shift the optimal amount of the other.

READER COMMENTS

dj

Nov 16 2014 at 1:40pm

I don’t think this quite answers the intuition behind the “lower interest rates -> more investment” proponents’ belief.

Suppose that the government knows that it’s going to need to repair some bridges in the next 10 years. The bridges aren’t crumbling yet, but sooner or later it’s going to be time to invest in fixing it.

Now interest rates drop to very low levels. The price of repairing the bridges has fallen relative to expectations. Doesn’t it become more attractive to do the investment now?

Andrew_FL

Nov 16 2014 at 2:49pm

As far as I can tell, the argument really amounts to:

if you’re going to borrow money, it is presently a good time to do so. Cue talk of insanity of not running as big of deficits as possible now so we can get them out of the way while they are “cheap.”

The presumption seems to be that the government is going to have to borrow money eventually (never mind, that it is already doing so). That the things that it needs to do are just so important that they will eventually have to be done, and, allegedly, we’d be better off doing them with borrowed money rather than doing them with present revenue.

I don’t know how to deal with that attitude when one rejects it’s every premise?

Scott Sumner

Nov 16 2014 at 3:16pm

dj, You asked:

“Now interest rates drop to very low levels. The price of repairing the bridges has fallen relative to expectations. Doesn’t it become more attractive to do the investment now?”

Not if the cause of the lower interest rate is declining marginal productivity of public investment.

Joe Teicher

Nov 16 2014 at 3:27pm

It seems like we should look at the difference between public sector and private sector borrowing costs. If public borrowing gets a lot cheaper than private borrowing, it seems like the state should do something to take advantage of that. I don’t know if increased infrastructure spending is the best answer but it’s at least something.

If public sector borrowing got a lot more expensive than private sector borrowing, wouldn’t you say the state needed to cut spending?

ThomasH

Nov 16 2014 at 4:20pm

I don’t understand your reasoning. It seems to me that if interest rates drop, some of the projects that a public sector does (that require investment today to produce benefits in the future) that had negative NPVs at “high” interest rates will have positive NPVs at “low” rates. (If there is unemployment of resources in genenral, this will also reduce investment costs and push the decision toward investment.)

The decision to increase public investment does not, as far as I can see, depend on knowing whether there has been a sudden increase in the supply of savings or a sudden decrease in the demand for investment goods. [There are probably some scenarios involving weird central bank reaction functions that might lead a central government to try to offset a sub-optimal monetary policy by reducing investment when interest rates fall but there would probably be other functions that would reinforce the orthodox result. These should be looked at as efforts to “participate” in monetary policy rather than pure investment decisions.]

What am I missing?

ThomasH

Nov 16 2014 at 5:15pm

@ThomasH

I agree that a fall in interest rates could happen at the same time as a decrease in the prospective yields on public investment. In that case, sure, public investment should not go up (or maybe go down). But I’d still say that the public sector investment function does not essentially depend on knowing why interest rates have changed.

ThomasH notices a fall in the price of pistachio ice cream (his favorite)! Was this because a drought in California caused growers to dump pistachios on the market? Was it because a sudden consumer aversion to pistachios? Why should he care? He’ll just buy more pistachio ice cream. [OK, maybe the reason of the sudden aversion is that it became known that ISIS is a major supplier of pistachios and he shares the aversion so his consumption of pistachio ice cream goes down not up. Does this count as correctly “not reasoning from a price change?”]

ThomasH

Nov 16 2014 at 5:35pm

Not if the cause of the lower interest rate is declining marginal productivity of public investment.

A very important clarification. 🙂 The public sector should increase investment in response to a decline in interest rates unless the decline in the interest rate was caused by a decline in the productivity of public sector investment.

Matt Moore

Nov 16 2014 at 6:08pm

Scott – I think you should be a little more careful in distinguishing between someone “reasoning from a price change” and “reasoning from a price”.

Markets are generally good because (among other things) they allow prices to summarise a lot of the relevant information needed for economic decision making.

Therefore, while saying, “the price of credit has fallen, so it is a good time to invest” is wrong (as you point out), saying “the price is low, so it is a good time to invest” is trivially true.

I think often what people are saying is that the credit price is absolutely low, relative to alternative uses of the funds, rather than is relatively low, relative to historic prices of credit.

Andrew_FL

Nov 16 2014 at 8:38pm

@Matt Moore-Here’s an example some one exactly reasoning that “the credit price is….relatively low, relative to the historic prices of credit.” And exactly, on that basis, reasoning that now is a more appropriate time to borrow money than any other time in recent history, because of a change in interest rates.

Scott Sumner

Nov 16 2014 at 9:56pm

Joe, Sure, any change in the spread might be relevant.

Thomas. Yes, we should continue doing cost/benefit analysis, and use the lower rate when doing so. My point is that there is no reason, a priori, to expect the “optimal amount” of public investment to rise when rates fall. I’m pretty sure the optimal amount of investment in Japan today is far lower than in the 1970s and 1980s.

Matt, I’m saying don’t jump to conclusions about where the equilibrium quantity is going as a result of a change in price.

Sure, prices are very useful to individuals.

bill woolsey

Nov 16 2014 at 10:13pm

If investment demand shifts to the left, then the lower interest rate raises quantity of investment demanded as well as reduces quantity of saving supplied.

Increased government investment would be an element of that increase in quantity of investment demanded.

maynardGkeynes

Nov 17 2014 at 6:53am

@ThomasH: Not sure I follow your clarification/acceptance of Prof. Sumner’s response — isn’t the marginal productivity of every investment likely to decline when you make more of it? Isn’t that why it’s called “marginal’? When you have built one bridge over the Hudson, isn’t the marginal productivity of the next two or three likely to be less? And, how would one ever know to what extent, if any, a decline in interest rates can be attributed to a decline in the marginal utility of public investment? At the very least, as a policy tool, it strikes me a rather useless formulation.

Scott Sumner

Nov 17 2014 at 8:43am

Bill, That’s right, but it’s equally true for private investment. My point is that there is no reason to expect the EQUILIBRIUM quantity of either type of investment to rise, as low rates may reflect a shift in the public plus private investment schedule to the left.

Yancey Ward

Nov 17 2014 at 11:56am

What happens at the rollover of the debt? I keep coming back the very first comment when I think about these sorts of things:

Now consider this- suppose the government knows that it is going to need to repair/replace some bridges in the next 20 years- the next 30 years, the next 40. How does one know where to stop in this line of argument?

We know for certain that the government will need to borrow in the future to pay Social Security benefits. Why not just borrow it all now and buy the future recipients annuities? After all, rates are at historic lows.

Sebastian H

Nov 17 2014 at 1:53pm

“We know for certain that the government will need to borrow in the future to pay Social Security benefits. Why not just borrow it all now and buy the future recipients annuities? After all, rates are at historic lows.”

This falls into a fallacy that I don’t know the name of. I’ll call it the Wall Street fallacy. Financial ‘investments’ are ultimately not investments in the same sense as creating an ongoing business concern, building a structure, or even trading a commodity. Wall Street likes to talk about financial investments as if they were precisely the same as other investments but they aren’t. It doesn’t make sense for a government like the US federal government to make ‘financial investments’ a priority over other investments because all financial investments ultimately depend on the success of the other investments. Why should the US government pay into the middle man?

The financial sector does real and important things in getting ‘real’ investments off the ground. But there is something wrong in treating financial investments precisely the same way as ‘real’ investments. There is probably something wrong with the way that the economy is functioning that the financial sector keeps growing compared to the (I don’t even know what to call it, ‘productive’ sounds very judgmental) rest of the economy.

I’m not nearly enough of an economist to know what the problem in analysis is. But I’m fairly certain that there is a locus of problem analysis there.

maynardGkeynes

Nov 17 2014 at 5:50pm

@Sebastian: One fallacy that strikes me is that current rates internalize the likelihood of both higher rates and lower rates in the future, and that it’s therefore impossible to declare that we are now at historic low rates. If we could, rates would instantly go higher.

Ray Lopez

Nov 17 2014 at 11:21pm

@maynardGkeynes – I think that’s right. It’s like stock market prices, which change when large buy/sell orders appear. When and if governments decide to start borrowing money for infrastructure, the rates will change and go higher. Another good chart to show low rates is here: http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1485/interest-rates/historical-real-interest-rate/

myb6

Nov 18 2014 at 5:08pm

Scott you have a good point that low interest rates might just reflect a low need for investment. But there are a couple links in the chain from low-interest-rates to low-expected-returns-for-individual-public-investment-projects. Each link weakens the argument.

In other words, if indeed low interest rates are a price merely reflecting the market’s perfectly rational reduced-expectations for the value of potential investments, those reduced-expectations still might be a smaller effect than the cost-reduction from the lower-rate.

Another interpretation, from a rational-market viewpoint: flight-to-safety is merely the market screaming for public investments. Like any firm, it would make sense for the corporate public to do its borrowing when the market is approving of the timing. I do wish our public institutions would do more project-specific borrowing, to keep the expectations for the project honest, but maybe that’s a rational response to transaction costs and low liquidity.

Comments are closed.