This post may upset some people, but I am simply trying to describe the world as it is, not as I would wish it to be. I recently spoke with Ryan Hart, who is researching the legal status of Fed policy. That got me thinking about the Fed’s mandate, and whether it is legally enforceable.

The Fed is an independent agency, but not as independent as some other agencies. For instance, the Fed chair can be fired without cause, and that’s not true of some other agency heads. But in other respects, the Fed seems to be “above the law” in a way that is almost unique in the American system, at least as far as I know. (Please correct me if I am wrong.)

When agencies like the EPA decide on a new policy, such as calling CO2 a form of pollution, the decision often ends up in the courts. But that’s not true of Fed monetary policy decisions. Why not? My theory is that this seeming immunity from legal oversight is a product of the Fed’s strange history. It was not created to do what it currently does, which is target inflation.

Broadly speaking, Fed history can be divided up into three periods:

1. 1914-68: A gold price peg (actually two pegs).

2. 1968-81: The Great Inflation

3. 1982-present: Inflation targeting

Under the gold standard, a central bank is unable to target inflation at 2%, at least for any extended period of time. When the Fed was created, no one imagined that they would engage in inflation targeting. Thus no thought was given to a Fed mandate to stabilize the macroeconomy, although lawmakers certainly hoped that the lender of last resort provision would reduce banking instability.

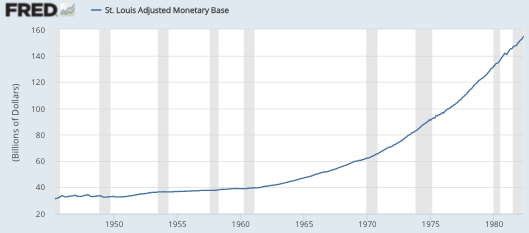

During the 1970s, the Fed did have the power to control inflation. So why didn’t they? Their failure was due to the fact that the Fed, as well as most outside economists, didn’t realize that they could control inflation. Milton Friedman understood, but many Keynesians, even highly distinguished Keynesians, blamed inflation on everything except monetary policy—labor unions, budget deficits, oil shocks, even crop failures in the Soviet Union. Today these theories seem silly, but they were taken very seriously at the time. For some reason, almost no one connected the post-1965 orgy of money printing with the mid-1960s upswing in inflation:

In order to understand the Fed’s “dual mandate” you need to understand the time period in which it was enacted. In 1977, Congress gave the Fed a mandate for stable prices, high employment and moderate long-term interest rates. But Congress was not giving the Fed a target, they were essentially saying; “It would be nice if we lived in a world of stable prices and high employment; in the off chance that there is anything you guys at the Fed can do to make it happen, please do so.” I don’t think anyone in Congress seriously thought the Fed could just pick an inflation rate, like 2%, out of thin air and target it.

How did the Fed react after being given the mandate for “stable prices”? Here’s how:

Year—CPI Inflation

1977–6.5%

1978–7.6%

1979–11.3%

1980–13.5%

1981–10.3%

Prices rose 60% in 5 years. Unemployment also rose in 1980, and longer-term interest rates hit an all time record of around 15% in 1981. I think it’s safe to say that these numbers are not what Congress had in mind. But no legal action was taken against the Fed, and indeed the Fed was not even blamed for the inflation. Again, the mandate was not viewed as a Fed target, and when the Fed sharply cut interest rates in the summer of 1980, despite 13% inflation, it was obvious to everyone that they were not targeting 2% inflation, and few people cared. (BTW, Paul Volcker did that insane easy money policy in mid-1980.) So if the courts were ever going to adjudicate a case against the Fed using the “original intent” approach, the Fed would win in a heartbeat. There was obviously no Congressional intent for the Fed to stop inflation.

Of course the Fed eventually did begin targeting inflation, at around 2% since 1990. But this was not because of the Congressional mandate, which as we saw the Fed ignored in 1980, but rather because they began to understand the ideas of Milton Friedman—persistent inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. When the Fed succeeded, outside observers were stunned, flabbergasted. Almost no one had thought this was possible. Alan Greenspan (who liked to speak in cryptic ways) was viewed as some sort of a magician, a “maestro.” John McCain suggested that if Greenspan died his body ought to be propped up and kept in place, as in the film Weekend at Bernie’s.

Of course all this was wrong; keeping inflation close to 2% is easy, and other central banks also succeeded. Today many economists (including me) are horrified by the Fed missing on the low side by 1%, an accuracy that would have been viewed as mind-bogglingly impressive in the 1970s.

Because outsiders were impressed by the Fed’s success in controlling inflation, the Fed rose even further above the law. Now any outsider who wanted to tinker with the Fed was seen as a crackpot, and the Fed became a sort of mysterious temple, which is far above politics.

So that’s how we got to where we are today. Yes, in theory the Fed has a “mandate.” But in practice the Fed can do whatever it thinks best (obviously within reason) and no one will stop them. In practice, the Fed tends to adhere closely to the consensus view of mainstream macroeconomists, so any court case against the Fed would face the uphill battle, with the economics profession closing ranks around the Fed, perhaps even testifying in their favor. Lots of luck winning that sort of case in Federal court. Do you know any Federal judges that want to go down in history for having caused a Great Depression, or Great Inflation? Neither do I.

PS. This post describes the Fed’s role on monetary policy; nothing I said applies to banking regulation, which is much more political.

READER COMMENTS

Emerson

Nov 24 2015 at 12:43pm

The Fed is above the law…. Well mostly that is true, but not entirely true..

The Fed has a vague mandate of full employment and stable prices (also low long term interest rates, but that is obscured by the first two)

Legally, the Fed cannot explicitly target inflation, although in reality, they do (sort of). Legally, the Fed cannot target GDP growth, Although in reality they do(sort of).

In order to create a Monetary Policy rule, congress would have to act. There are many good possible rules: Taylor Rule, Specific Inflation Targeting, Friedman ‘s Rule ( replacing the FOMC with a computer programmed for steady M2 growth). Some people are still In favor of the gold standard as a policy

rule.

And of course most people who read this blog favor the NGDP level targeting rule( as do I).

But until Congress acts ( which would require congress to seriously consider and understand a Complex issue- not very likely) it seems the Fed will have to continue on its path of discretionary policy while pretending to be in compliance with its 1977 vague triple mandate.

Radford Neal

Nov 24 2015 at 12:51pm

My recollection from the 1970s is that all competent economists actually DID realize that central banks could control inflation, if they were determined to do so, but most then argued that the cost in unemployment, etc. would be unacceptably large. They talked about the Fed “validating” inflationary wage settlements, for instance, with the implication being that if it stopped “validating” them, the inflation could not continue.

At least that’s what they said to other economists. The public was considered too immature for such sophisticated arguments, however, so economists regularly made statements about how inflation was the result of greedy businesses, greedy unions, etc. (as dictated by their ideology), without mentioning the little matter of “validation” by the Fed. You wouldn’t want ordinary people asking whether “validation” was actually necessary…

Njnnja

Nov 24 2015 at 1:21pm

Your assessment of the Fed as a very strange entity is spot on. If you go back to the Aldrich-Vreeland Act upon which the Federal Reserve Act was built, what was intended was really just a lender of last resort to deal with bank panics. But there was already a lot of populist concern that banks were out of control, and creating a “bailout institution” would only exacerbate the problem (hmmm sounds familiar), not to mention the concerns about the public impact of any sort of banking oligopoly (“People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public” and all that). So a bargain was struck, where the Fed would be given powers to deal with bank panics, and the “member banks” could work together, but there must be some level of public oversight and geographical representation (i.e., not just east coast banks). Hence the weird checks and balances that look like nothing else.

So what does inflation have to do with any of this? Well, the most straightforward way to deal with a high demand for currency (that would cause a bank panic) is to write some script (like California did just a few years ago). And once you say that the Fed is allowed to somewhat arbitrarily issue currency during bank panics, it’s not a big step to make them responsible for controlling the money supply all the time.

Phil

Nov 24 2015 at 1:44pm

I cannot imagine a case that would be justiciable. Who would have standing to sue? On what legal basis would a monetary policy decision be decided? I strongly suspect the courts would conclude a complaint about monetary policy is a political question, not a legal one.

foosion

Nov 24 2015 at 4:07pm

Regulations that an agency (such as the EPA) publishes are generally subject to the Administrative Procedures Act, which provides for notice, public comment and judicial review.

The Fed’s actions in setting interest rates do not seem to be regulations.

Scott Sumner

Nov 24 2015 at 6:29pm

I agree with most of the comments. Regarding the 1970s, it might be more accurate to say that economists didn’t think the Fed could control inflation without imposing unacceptable costs on the economy. Certainly the term ’cause’ is tricky, and subject to multiple interpretations.

John Thacker

Nov 24 2015 at 7:57pm

The Fed is certainly “above the law.” The law creating it requires that Fed Governors be chosen from many different areas and industries, and that no two Fed Governors be from the same state. This law is constantly flagrantly violated, and no one cares.

James

Nov 24 2015 at 10:56pm

Scott:

When Bernanke spoke about letting Lehman go under in 2009, he said “I will maintain to my deathbed that we made every effort to save Lehman, but we were just unable to do so because of a lack of legal authority.” So, either Bernanke was being dishonest or he genuinely believed that there are some laws limiting what the Fed can do.

Emerson:

If the Fed were to implement an NGDP targeting policy, what do you believe the outcome would be? I’m really hoping to find someone who claims to favor NGDP targeting who will give point estimates and confidence intervals conditional on NGDP targeting for some set of macroeconomic variables e.g. “The volatility of YoY NGDP growth will drop by a third.”

My own guess, for what it’s worth, is that if Congress passed a law requiring NGDP targeting, the people at the Fed would be constantly changing their stance on the appropriate level of NGDP to target. In effect, the Fed would just do what they want, just like now, but they would use different language to report their actions. We’d wind up with no change in any macroeconomic variable of more than 1 standard deviation.

ThomasH

Nov 25 2015 at 8:03am

I do not see the Fed’s motivations right now quite the same way. I agree that no Fed decision is likely to be challenged in court, but it is subject to more constraints than “mainstream macroeconomic opinion.” “Mainstream economic opinion” was not aghast at the QE’s. Nor was it braying that hyperinflation was just around the corner and that QE should be stopped now now now. Nor is it that ST interest rates should be increased before the 2% trend price level has been achieved. Those are the crackpot opinions of “media macro,” inflation hawks, and gold bugs who have a home in one of our major political parties. This, not “mainstream macroeconomic opinion” was the political pressure that has prevented the Fed from acting more vigorously to promote a quick recovery from the recession. Mainstream macroeconomic opinion did see a role for fiscal policy during this period of constrained Fed action (and I would argue it accepted the constraints too easily), but it did not prevent the Fed from acting.

I also have a slightly different recollection of the Great Inflation. I do not think that macroeconomists at the time believed that the Fed “could not” stop inflation. They believe that the tradeoff against unemployment was too high and that silly thinks like WIN buttons and price controls could reduce that trade-off. In fact, the Volker recession was in fact quite severe, so their concerns were not totally without foundation, although worth it.

JJ

Nov 25 2015 at 10:23am

Scott,

Which kind of economists were the ones who believed that Price Controls could fight inflation? Was is it the Keynesian economists of the 1970’s? If so, where in the Keynesian Theory does it state that price controls could ever be effective?

Scott Sumner

Nov 25 2015 at 1:24pm

James, It looks like you didn’t read my entire post. Read the very end.

Thomas, I don’t agree, I think mainstream opinion in economics does support an interest rate increase in December. I wonder if there are any polls.

JJ, Yes, it was Keynesians, and a few non-Keynesians. The idea was that price controls could overcome the sticky wage/price problem.

James

Nov 25 2015 at 3:42pm

Scott, I read every word. I see targeted bailouts as another Fed function separate from monetary and regulatory activies. I believe all of these are above the law.

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Nov 26 2015 at 12:45pm

Although I have nothing against institutions that rise from good practices, I think that this historical perspective is useful to realize that the FED can benefit from a clearer target and accountability provisions.

Barry

Dec 10 2015 at 12:41pm

Radford Neal writes:

“My recollection from the 1970s is that all competent economists actually DID realize that central banks could control inflation, if they were determined to do so, but most then argued that the cost in unemployment, etc. would be unacceptably large. They talked about the Fed “validating” inflationary wage settlements, for instance, with the implication being that if it stopped “validating” them, the inflation could not continue.”

And note that the working and much of the middle class was decisively and deliberately crushed by Volcker and Reagan.

Comments are closed.