For the second time in six months, the world’s equity markets have been roiled by a tiny downward move in the Chinese currency. It seems unlikely that this is mere coincidence. And yet I’ve yet to see a convincing explanation of why the Chinese currency should influence global equity markets. Even worse, the explanations that are being offered are often totally wrong, not even consistent with basic economic theory. Consider this example:

China accelerated the devaluation of the yuan on Thursday, sending currencies across the region reeling and domestic stock markets tumbling, as investors feared the Asian giant was kicking off a virtual trade war against its competitors. . . .

The People’s Bank of China again surprised markets by setting the official midpoint rate on the currency at 6.5646 yuan per dollar, the lowest since March 2011.

That was 0.5 per cent weaker than the day before and the biggest daily drop since last August, when an abrupt near 2 per cent devaluation of the currency also roiled markets.

The impact was immediate as regional currencies went into a tailspin. The Australian dollar, often used as a liquid proxy for the yuan, fell half a US cent in a blink.

Shanghai stocks slid 7 per cent to trigger the halt in trading, a repeat performance of Monday’s sudden tumble. Japan’s Nikkei shed 1.8 per cent in sympathy.

A sustained depreciation in the yuan puts pressure on other Asian countries to devalue their currencies to stay competitive with China’s massive export machine.

It also makes commodities denominated in US dollars more expensive for Chinese buyers, which could hurt demand and thus further depress commodity prices in a vicious chain reaction.

There’s a lot here, and none of it makes any sense at all. Let’s start with what we do know.

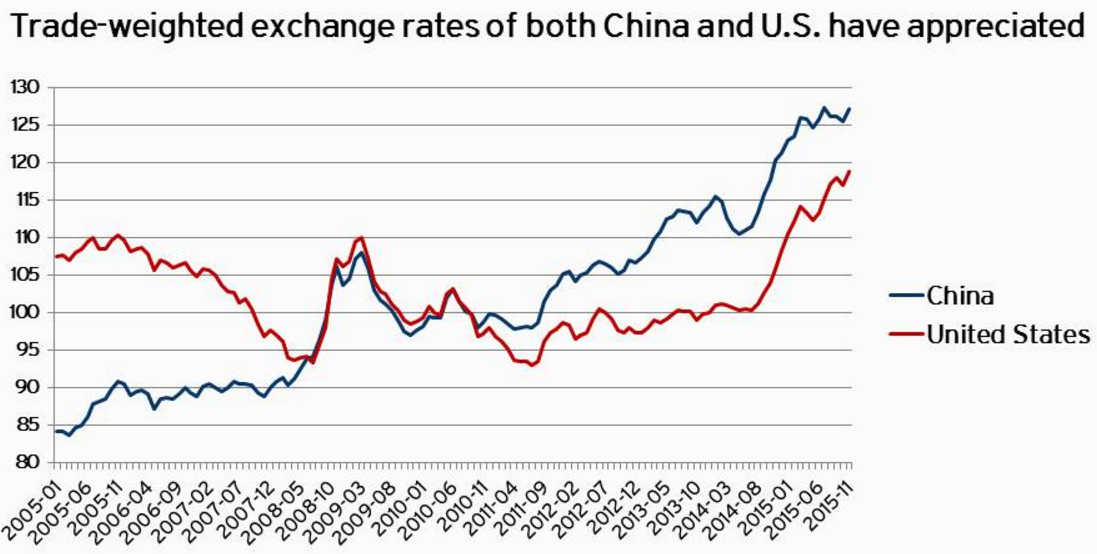

1. The Chinese currency has been very strong in recent years, rising sharply in trade weighted terms. It is still very strong today. Nothing significant has happened to the value of the Chinese currency. Whatever problems the world economy has, a weak Chinese currency is most certainly not one of them.

2. The fact that commodities are priced in US dollars is completely meaningless, because commodity prices are not sticky. The US dollar price of commodities around the world would be precisely the same if they were priced in Swiss francs, Mexican pesos, or Zimbabwe dollars. It only matters which currency a product is priced in if the price of that product is sticky. Commodity prices are not sticky.

3. Whatever problems the world has, rising commodity prices for Chinese buyers is certainly not one of them. Commodity prices in China have been plunging sharply lower in recent years, as the yuan has gotten stronger and stronger. The last few days have seen Chinese commodity prices fall even lower.

4. A 1/2 cent fall in the Australian dollar is not a “tailspin.”

The claims in the article are not just slightly wrong, or debatable. They are almost 180 degrees off base. Almost describing the exact opposite of what has actually occurred. Here’s the value of the yuan in trade-weighted terms:

So then why did this Chinese action, as well as the previous tiny exchange rate adjustment a few months ago, seem to have such a big impact on markets?

I don’t know.

The global markets seem to have reacted as if they were being hit by a deflationary shock. Here’s my best guess, which is admittedly not very satisfying:

Something happened to reduce the perceived global Wicksellian equilibrium real interest rate. For instance, perhaps investors reduced their forecast of Chinese investment. Because central banks throughout the world target interest rates, a lower Wicksellian rate makes monetary policy tighter, as a side effect. Thus expected growth in global NGDP is lower.

The problem with my explanation is that it’s not clear why the Chinese action would lead investors to lower their estimate of the global Wicksellian rate. After all, the Chinese move would seem to be an expansionary monetary policy shift. On the other hand Chinese stocks fell more sharply than stocks in other places, suggesting that whatever shocks hit the market, hit China the hardest. And if you don’t trust the Chinese market (and there are good reasons not to trust it) then you must still account for the sharp fall in Hong Kong stocks.

Another possibility is that although the yuan is currently very strong, the recent action might have led investors to expect a sharp future devaluation. That would explain why there was a big reaction to such a small move in the exchange rate, but still wouldn’t explain the direction of the reaction. Why wouldn’t Chinese stocks rise? The US stock market rose when the US devalued in 1933 and in 2009. Dollar denominated debts? Perhaps, I don’t know how common those debts are in China. But the effect of a 0.5% devaluation against the dollar seems trivial, relative to a 7% fall in the Chinese market.

Another theory is that the devaluation signals worry about the economy within in the Chinese government. The markets are just waiting for “the other shoe to drop.” Maybe, but the previous exchange rate shock was not followed up by any notable news. Markets soon recovered. The consensus forecast for Chinese growth has not changed much in recent months, although it has dropped slightly. When will we see these dramatic events out of China?

To summarize, I think the most probable explanation has something to do with the Chinese action making monetary policy more contractionary throughout the world. That may be related to a perception of slower Chinese growth, which reduces the global Wicksellian interest rate. But we still have no explanation for why a tiny reduction in the value of the yuan, after years of strong appreciation, should have a big impact on either Chinese growth or global markets. As Napoleon might say:

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

PS. Some commenters misunderstood a previous post I did on China. I do not support the government’s current policy stance; I think monetary policy in China is too contractionary.

READER COMMENTS

TravisV

Jan 7 2016 at 4:10pm

In case you haven’t seen it, some commentary on this topic from smart analysts:

http://marketmonetarist.com/2016/01/05/pboc-should-stop-the-silliness-and-float-the-rmb

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2015/08/how-to-create-chinese-economic-crisis.html

Andrew

Jan 7 2016 at 4:27pm

Isn’t a more reasonable explanation the fact that the Fed has begun to tighten monetary policy in a world that can’t take it and the markets are correctly discounting a future path of monetary policy that is simply too tight?

The market briefly went up after the fed increased rates due to short covering and has been on a solid downward trend since the day after the last Fed meeting. Oil is collapsing. Emerging markets are collapsing. Commodity currencies are collapsing. Isn’t this what happens when policy makers make an unforced error and tighten policy prematurely? Didn’t the same type of thing happen in 2011 after the ECB increased rates in the spring of that year? 2011 was a horrible year for markets because of a small but totally misguided increase in rates from a single central bank. Couldn’t this just be a replay?

With China’s currency being fixed to the USD, their monetary policy has tightened pretty dramatically over the last little while.

This all seems like a classic deflationary shock emanating from a policy mistake from the Fed. The minutes yesterday certainly had something to do with this. You’ve got falling inflation and a bunch of policy makers expressing major concerns about the outlook for inflation and they go ahead and raise rates anyways based entirely on their phillips curve model.

The world now knows (before they weren’t sure) that the Fed is not data dependent and is going to raise rates four more times this year regardless of what happens with the inflation rate. It is now sinking in and the market is responding appropriately to tighter than expected (and tighter than appropriate) monetary policy.

ThaomasH

Jan 7 2016 at 4:40pm

These are the people — Macro Media, inflation hawks — that you and Krugman are up against.

A weaker Yuan consistent with more expansive Chines CB policy would be good for the world.

It seems that the Fed’s problem is that it is skittish about having to raise rates quickly. I’m familiar with models that show how uncertain price levels are bad for growth — that why central banks supposedly target price level trends (even if they fail to follow through). I have never seen a model in which large changes in ST interest rates are detrimental. Is it just coincidence that financial institutions want reduce uncertainty about ST interest rates?

E. Harding

Jan 7 2016 at 4:55pm

Could this have something to do with foreign debt, or greater difficulty in Chinese purchases of foreign property?

Frank Taussig

Jan 7 2016 at 4:57pm

Sorry I cannot help myself from being a stickler.

The ” Riddle wrapped in a mystery…..” is Churchill from a 1939 radio address, he is talking about Russia vis a vis Germany . The next few words in the quote are great and sadly always left out…..

“I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key.”

James Alexander

Jan 7 2016 at 5:16pm

Scott. Your post shows the imperfection of EMH. It can’t cope with sentiment changes. Lars (via Travis) and Andrew can see what mayhem the Fed have been and are causing, as have other MM’s (ahem). It’s right that the Fed should ignore China’s economy, but it’s also a fact China’s tied its monetary policy to the US, more fool them.

Markets can spin out of control if they lose confidence in monetary authorities even if it doesn’t exactly coincide with any concrete move. Both the Fed’s and China’s. Now China appears to be panicking and sowing confusion. And Fischer lecturing markets on their “wrongly” dove’ish rate expectations wasn’t exactly helpful, of course.

Scott Sumner

Jan 7 2016 at 5:25pm

Thanks Travis.

Andrew and Thomas, All that may be true, but I am trying to explain the specific situation where a small depreciation in the yuan triggers a big market sell off. Why should the US stock market care so much about a small depreciation of the yuan?

Frank, Yes, I only steal from the best.

Scott Sumner

Jan 7 2016 at 6:08pm

James, I am quite aware that markets can plunge if they lose confidence in monetary policymakers. That’s my view of what happened in 2008. But that doesn’t explain why Chinese currency adjustments are a trigger.

Also recall that I’ve been consistently right about the market dips since 2009.

dlr

Jan 7 2016 at 6:11pm

Scott, I think it’s about the PBOC reaction function. Going in, the market’s view of it might be described as “they will do everything they can to stretch the limits of the Trilemma by minimizing forex volatility but still appearing to do loosening type things, but if things get really dire, they’ll hopefully give up in time and avoid disaster by further relaxing the peg such that they can adequately loosen policy.”

After the modest August devaluation, they were clearly still in cake-and-eat-it-too mode, for example predictably keeping the fix aggressively manipulating the growing spread between offshore and onshore CNY that would have otherwise signaled the market’s expectation for further depreciation, while still uselessly doing optical things like lowering reserve rates. There is probably a happy albeit unlikely equilibrium where this carries the day, but people got more pessimistic about what is really going on inside China as commodity prices continues to plunge and Caixin IP #s came in weak.

So when conditions worsen and oil and copper and iron ore drop every day and the Shanghai markets start to tremble again, people expect the PBOC to either pretend nothing is wrong or come to jesus. But they do neither, and instead bump the fix outside of anyone’s expectation twice in a row. This is not their m.o. and people think they are now willing to go even further to protect their illusion of FX control at the expense of a catastrophically tightening policy. They gave the market a mild, opaque surprise. Like someone who has been trying to cut down on sugar instead of taking Lipitor. If they come back from the doctor and say, I’m going to cut down a little more on sugar, no further comment, you immediately hit maximum worry. Results were probably bad and they may never take the medicine in time. It might seem like the move was small and in line with trade-weighted depreciation but for the PBOC it was a departure from expectations after the local market’s negative reaction to the previous day’s move and the strong signals being sent by commodity prices.

marcus nunes

Jan 7 2016 at 6:11pm

In a sense, China is the US “multiplier”. The US tight MP implies tight MP in China (through the peg). Movements in China, interpreted as attempts to free itself from the “shakles” cause all sorts of “indispositions”, at least until the (or a) new monetary regime is established.

A US/China tightening is certainly a world deflationary shock.

Rajat

Jan 7 2016 at 6:51pm

“Another theory is that the devaluation signals worry about the economy within in the Chinese government.”

In the absence of a better theory/explanation, I would go with this. Lately at least, markets seem to have moved immediately in ways consistent with the idea that central banks know more about the economy than the markets do. For example, US shares rose on December 16th – the day of the Fed’s rate increase. That said, market moves consistent with CB-omniscience don’t seem to have persisted, with the S&P500 falling on the 17th and 18th of December. Perhaps that means it’s time to buy?

ThomasH

Jan 7 2016 at 7:42pm

@ marcus

But should the devaluation not be seen as permitting/consistent with less tightness of pboc, which should be good for the US economy? They are offsetting a bit of the Fed’s inappropriately tight money.

Benjamin Cole

Jan 7 2016 at 8:32pm

The PBoC, probably infected by western central bankers, was foolish to peg to the dollar or to fret about inflation. Let us hope the PBOC goes back to his old ways. Print money baby

H_Wasshoi(twintail)

Jan 7 2016 at 9:13pm

Inflation targeting don’t offer nominal stability.

The world CBs are doing IT. So, some shock affect severely the world.(my understanding)

In fact, tightening MP is US. not China.

China’s NGDP path is (will be) well anchored.(I think)

If you allow anti-EMH models here,

I think momentum model is working on the Chinese stock market.

http://www.nber.org/papers/w21771

1.Beginning of the new year. January

(maybe, tax trigger)

2.The most market participants in China is not “sophisticated” (unskilled poor individual traders)

So it has occurred landslide of the stock price.

While, Yuan becomes a little bit weak.

In addition,the US and China is a very complementary trade partner today.

Tighting US MP hurts specially large cap companies which is likely to do international trade.

(also hurts international trade)

(See stock price change of shipping company of each countries, e.g. Japan not so affected)

It explains also the reaction of the HK market.

Those above are my rough sketch (guess).

Sincerely

Scott Sumner

Jan 7 2016 at 10:01pm

Dlr, I’m not sure I follow that. Are you saying that markets would have rallied if China had let the yuan float? And that the small devaluation showed they were afraid to do that?

(I think that’s possible, but I just want to be sure that’s your claim.)

Marcus, But why the move in response to a small devaluation?

Rajat, You said:

“For example, US shares rose on December 16th – the day of the Fed’s rate increase.”

It’s far more likely that this was in response to the statement. We have 100s of data points saying the market thinks it’s smarter than the Fed, and it usually is.

TheNumeraire

Jan 7 2016 at 11:09pm

The market action is especially puzzling when viewed through the lens of the market monetarist model. Doesn’t the MM model suggest that when NGDP growth is decelerating well below medium-to-long-term NGDP trend growth that any expansionary monetary policy should be welcomed as positive? Furthermore, shouldn’t the positive monetary effects in a large international trade nation such as China far exceed the negative rest-of-the world currency effects?

dbeach

Jan 7 2016 at 11:24pm

I think your explanation #3 is correct, that the market regards the devaluation, however small, as a signal that the government is worried about a hard landing, and since many people don’t trust Chinese economic data, they instead engage in this kind of Kremlinology to try to guess where the economy is “really” headed.

Personally I think this is a bizarre interpretation of the move, because if the government really were concerned about a serious drop in growth and all they did was this measly 50 bps devaluation of the currency, they wouldn’t be doing nearly enough. And the way they’re managing this process is really weird; why devalue 50 bps in one day instead of just walking down by 10 bps every day for a week? It’s as if they want to spook everyone.

Gordon

Jan 8 2016 at 2:29am

Scott, isn’t there a possibility that it’s more than just news from China weighing on the markets? This past week we’ve seen news about a contraction in industrial production in the US. Analysts have been lowering their forecasts for Q4 US real GDP growth. The World Bank lowered its forecast for global GDP growth in 2016. And there was a WSJ report discussing the FOMC minutes and how some FOMC members expressed trepidation over increasing the fed funds rate because of the lack of inflation. And that same WSJ article pointed out that when the November inflation data came in, there was no increase in PCE core inflation. This report plus all the other news may have raised serious doubts about the competence of the FOMC and whether a rate increase was justified.

RL London

Jan 8 2016 at 3:13am

I think the problem for the Chinese authorities is fairly clear, but it’s obvious they don’t know how to address it.

Over the last decade, the maintenance of the peg with the dollar has meant that China has been an amplifier of Fed policy. During the phase of falling real interest rates and QE, the Chinese experienced a dramatic expansion in domestic credit. This contributed to its domestic investment boom.

Now, the domestic investment boom has ended and Fed tightening is forcing an unpleasant tightening of credit conditions in China. Some Chinese officials believe this is a good thing as it will encourage deleveraging and the closure of industrial spare capacity. Others believe a growth slowdown is dangerous given a debt overhang and the potential for rising unemployment.

Neither side has a dominant position, so we end up with a compromise: small, periodic depreciations of the currency. The opaqueness around their policy intentions adds to investor nervousness inside and outside China. Capital outflows are picking up as investors worry about the health of the economy. The more that they try to manage the peg, the more they have to intervene and the more that domestic liquidity conditions tighten.

Inevitably, most sensible investors increasingly believe the renminbi has to fall much further. The Chinese authorities, like many others before them, are trying to resist using FX reserves. But we know from history this always ends in failure.

When the RMB finally falls much more sharply, it will impart a significant deflationary pulse to the world economy. Investors are anticipating this. Consequently, US, European and Japanese equity markets drop. As you say, the falls so far look modest. But there is no guarantee this will continue. Because we don’t know, we simply assume the worst about growth problems in China. This hasn’t been a bad heuristic in recent years.

Francois

Jan 8 2016 at 3:18am

Scott, I am astounded how you are missing the big picture here: the potential unwarranted monetary tightening that might take place in China

I would like first to describe how I see the conduct of monetary policy in China between 2000-2009. During that period, the PBOC bought billions of treasuries to prevent a rapid appreciation of its exchange rate. As a result, the monetary base expanded very quickly. Almost all the assets of the PBOC consisted of treasuries. Without compensatory action, this should have led to a very fast increase of nominal GDP and to strong inflation. However, the PBOC raised the mandatory reserve ratio continuously during that period, compensating the rapid increase of the monetary base by a reduction of the velocity of money. Of course, the undervalued exchange rate and the strong economy eventually attracted capital towards China, putting upward pressure on its exchange rate. Which the PBOC had to offset by buying more treasuries.

That process basically stopped around 2009. It seems that we are witnessing now the reverse process. There are strong private capital outflows out of China, putting some downward pressure on the exchange rate. For political reasons, the Chinese authorities do not want the exchange rate to depreciate too much. China apparently used some $500bn to defend the exchange rate.

As part of that defense, the monetary base in China has started to shrink towards the end of 2015. To compensate for that, the PBOC has reduced its interest rates, to inject more money into the domestic financial system. This has not been sufficient to prevent an outright shrinking of the monetary base towards end 2015. Logically, the PBOC has also started to reduce the mandatory reserve ratio, to increase the velocity of money. Exactly the mirror image of 2000-2009.

Still, Nominal GDP growth has already slowed down strongly in China. Inflation is below target. Debt levels are high for a country at that stage of its development, and there are already concerns about debt turning sour on a large scale. It is not very hard to see that there is no room for tighter money in China. The fall of the Chinese stock market might be a symptom of tighter money, with very unwelcome consequences for the Chinese economy, and for the world economy as well.

Ironman

Jan 8 2016 at 9:19am

Scott,

You might find some of the contemporaneous history for the market’s actions back in August helpful in understanding why U.S. markets went on the ride they did at the time.

Looking at what’s happened in the past week, there’s a repeating theme from August 2015 – after setting up their market’s new circuit breakers, Chinese authorities once again relaxed their other restrictions on selling activity, believing they would be sufficient to arrest downward pressure on Chinese stock prices. Days after taking effect, the circuit breakers are being dumped as restrictions on selling stocks are now being reimposed. Meanwhile, the same factors that initially drove such widespread selling activity are still there, with the pressure for selling growing because that activity has been forcefully constrained without sufficient improvement in China’s economy to relax it naturally as yet.

As for what’s happening in U.S. markets, the best way to describe what’s happening there is that investors are engaged in a dispute with the Fed over the number of rate hikes in 2016, with investors saying fewer and the Fed saying more. Recent falling stock prices are consistent with investors shifting their forward-looking focus from 2016-Q3 to 2016-Q2 as the likely timing for the Fed’s next rate hike. The activity in China’s markets is mostly coincidental to what’s really been driving U.S. markets.

James Alexander

Jan 8 2016 at 9:20am

Scott

The trigger is a bit of a side issue, a minor bit of new information, the general situation is the thing. And many people now see, thanks to you, that expected NGDP growth relative to monetary policy intentions is the core macro issue. What are they today in the US? Slowing and tightening respectively, and more so every day. I don’t like tipping point “theory” but it seems a good description of what happens in markets.

Jeff

Jan 8 2016 at 9:35am

I think it’s pretty obvious what’s going on. It seems that everyone except the PBOC knows a big devaluation or a float is coming, and they’re all placing bets on it. People like George Soros have made billions taking the other side of trades made by obstinate central banks. This time it’s so obvious that huge numbers of people are trying to get a piece of the action, so the crash is happening earlier than it usually does in these scenarios.

China should immediately stop throwing good money after bad and float the yuan. This will also strengthen the dollar and may force the Fed to roll back “liftoff”.

o. nate

Jan 8 2016 at 1:47pm

I agree with the view expressed by dlr and Jeff. The problem is that everyone knows the yuan wants to go lower, and the government is trying to prop it up. Under these circumstances, people will use whatever means they can to pull money out of Chinese markets and put it in hard assets or other currencies. If you had a freely floating rate and there was a quick devaluation, then I agree that Chinese stocks would pop (and if and when the devaluation occurs, that’s what I expect to happen), but in this situation people have an incentive to pull money out now and wait.

Comments are closed.