The latest reply from Mike Huemer on the ethical treatment of animals, this time with a cool graph.

Bryan Caplan posted this further comment on animal welfare arguments on his blog.

I didn’t have time to address this earlier (partly because I was

traveling for the talk that, coincidentally, Bryan Caplan invited me to

give at GMU, on an unrelated topic). I have a few comments now.

My main reactions:

I. The argument from insects has too many controversial assumptions to

be useful. We should instead look more directly at Bryan’s theoretical

account of how factory farming could be acceptable.

II. That theory is ad hoc and lacks intrinsic intuitive or theoretical plausibility.

III. There are much more natural theories, which don’t support factory farming.

I.

To elaborate on (I), it looks like (after the explanations in his latest post), Bryan is assuming:

a. Insects feel pain that is qualitatively like the suffering that, e.g., cows on factory farms feel.

b. If (a) is true, it is still permissible to kill bugs

indiscriminately, e.g., we don’t even have good reason to reduce our

driving by 10%.

(a) and (b) are too controversial to be good

starting points to try to figure out other controversial animal ethics

issues. I and (I think) most others reject (a); I also think (b) is very

non-obvious (especially to animal welfare advocates). Finally, note

that most animal welfare advocates claim that factory farming is wrong

because of the great suffering of animals on factory farms (not just

because of the killing of the animals), which is mostly due to the

conditions in which they are raised. Bugs aren’t raised in such

conditions, and the amount of pain a bug would endure upon being hit by a

car (if it has any pain at all) might be less than the pain it would

normally endure from a natural death. So I think Bryan would also have

to use assumption (c):

c. If factory farming is wrong, it’s wrong

because it’s wrong to painfully kill sentient beings, not, e.g.,

because it’s wrong to raise them in conditions of almost constant

suffering, nor because it’s wrong to create beings with net negative

utility, etc.

So to figure out anything about factory farming

using Bryan’s approach, we’d first have to settle disputes about (a),

(b), and (c), none of which are obvious, and none of which is really

likely to be settled. So this is not promising.

II.

What

would be more promising? Let’s just look at Bryan’s account of the

badness of pain and suffering. (Note: I include all forms of suffering

as bad, not merely sensory pain.) I think his view must be something

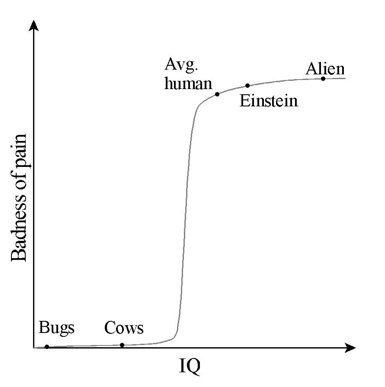

like what the graph below depicts.

As your intelligence increases, the moral badness of your pain increases. But it’s a non-linear function. In particular:

i. The graph starts out almost horizontal. But somewhere between the

intelligence of a typical cow and that of a typical human, the graph

takes a sharp upturn, soaring up about a million times higher than where

it was for the cow IQ. This is required in order to say that the pain

of billions of farm animals is unimportant, and yet also claim that

similar pain for (a much smaller number of) humans is very important.

ii. But then the graph very quickly turns almost horizontal again. This

is required in order to make it so that the interests of a very smart

human, such as Albert Einstein, don’t wind up being vastly more

important than those of the rest of us. Also, so that even smarter

aliens can’t inflict great pain on us for the sake of minor amusements

for themselves.

Sure, this is a logically possible (not

contradictory) view. But it is very odd and (to me) hard to believe. It

isn’t obvious to begin with why IQ makes a difference to the badness of

pain. But assuming it does, features (i) and (ii) above are very odd. Is

there any explanation of either of these things? Can someone even think

of a possible explanation? If you just think about this theory on its

own (without considering, for example, how it impacts your own interests

or what it implies about your own behavior), would anyone have thought

this was how it worked? Would anyone find this intuitively obvious? As a

famous ethical intuiter, I must say that this doesn’t strike me as

intuitive at all.

Now, that graph might be a fair account of most people’s implicit attitudes. But what is the best explanation for that:

1) That we have directly intuited the brute, unexplained moral facts that the above graph depicts, or

2) That we are biased?

I think we can know that explanation (1) is not the case. We can know

that because we can just think about the major claims in this theory,

and see if they’re self-evident. They aren’t.

To me, explanation

(2) thrusts itself forward. How convenient that this drastic upturn in

moral significance occurs after the IQ level of all the animals we like

the taste of, but before the IQ level of any of us. Good thing the

inexplicable upturn doesn’t occur between bug-IQ and cow-IQ (or even

earlier). Good thing it goes up by a factor of a million before reaching

human IQ, and not just a factor of a hundred or a thousand, because

otherwise we’d have to modify our behavior anyway.

And how

convenient again that the moral significance suddenly levels off again.

Good thing it doesn’t just keep going up, because then smart people or

even smarter aliens would be able to discount our suffering in the same

way that we discount the suffering of all the creatures whose suffering

we profit from.

I have no explanation for why features (i) and

(ii) would hold, but I can easily explain why a human would want to

claim that they do.

Imagine a person living in the slavery era,

who claims that the moral significance of a person’s well-being is

inversely related to their skin pigmentation (this is a brute moral fact

that you just have to see intuitively), and that the graph of moral

significance as a function of skin pigmentation takes a sudden, drastic

drop just after the pigmentation level of a suntanned European but

before that of a typical mulatto. This is a logically consistent theory.

It also has the same theoretical oddness of Bryan’s theory (“Why would

it work like that?”) and a similar air of rationalizing bias or

self-interest (“How convenient that the inexplicable downturn occurs

after the level of the people you like and before the level of the

people you profit from enslaving.”)

III.

A more natural

view would be, e.g., that the graph of “pain badness” versus IQ would

just be a line. Or maybe a simple concave or convex curve. But then we

wouldn’t be able to just carry on doing what is most convenient and

enjoyable for us.

I mentioned, also, that the moral significance of

IQ was not obvious to me. But here is a much more plausible theory that

is in the same neighborhood. Degree of cognitive sophistication matters

to the badness of pain, because:

1. There are degrees of consciousness (or self-awareness).

2. The more conscious a pain is, the worse it is. E.g., if you can

divert your attention from a pain that you’re having, it becomes less

bad. If there could be a completely unconscious pain, it wouldn’t be bad

at all.

3. The creatures we think of as less intelligent are also,

in general, less conscious. That is, all their mental states have a low

level of consciousness. (Perhaps bugs are completely non-conscious.)

I think this theory is much more believable and less ad hoc than

Bryan’s theory. Point 2 strikes me as independently intuitive (unlike

the brute declaration that IQ matters to badness of pain). Points 1 and 3

strike me as reasonable, and while I wouldn’t say they are obviously

correct, I also don’t think there is anything odd or puzzling about

them. This theory does not look like it was just designed to give us the

moral results that are convenient for us.

Of course, the “cost” is

that this theory does not in fact give us the moral results that are

most convenient for us. You can reasonably hold that the pain of a

typical cow is less bad than the pain of a typical person, because maybe

cow pains are less conscious than typical human pains. (Btw, the pain

of an infant would also be less intrinsically bad than that of an adult.

However, infants are also easier to hurt; also, excessive infant pain

might cause lasting psychological damage, etc. So take that into account

before slapping your baby.) But it just isn’t plausible that the

difference in level of consciousness is so great that the human pain is a

million times worse than the (otherwise similar) cow pain.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas

Oct 23 2016 at 11:51pm

Is it always wrong to kill sentient human beings? Most people would say no because most people think of self-defense as an inherent right (or biological imperative). There’s disagreement about what constitutes self-defense, e.g., whether it comprises killing non-combatants during wartime. But putting that aside, if self-defense is a reasonable justification for killing (some) sentient human beings, does it necessarily justify killing lesser animals? Living in a disease-free environment (e.g., roach-free) seems like an example of a good self-defense justification. What about killing animals for food because the meat of chickens, pigs, cattle, etc., is a relatively inexpensive source of protein? That’s certainly a kind of self-defense, or at least a biological imperative. (There’s an empathic or esthetic argument for raising and killing chickens, etc., humanely, but that’s beside the point that I’m raising here.)

Related discussion topic: Does anyone (other than an animal-rights extremist) believe that it’s all right for some animals (e.g., alligators) to kill and eat human beings, but it’s not all right for human beings to kill and eat some animals?

austrartsua

Oct 24 2016 at 1:09am

But why does everything have to be measured on one scale? Why should it be that the only difference between cow and human intelligence is once of IQ?

Why can it not be a difference in type? A qualitative difference in the way human consciousness works. Yes, humans are animals who evolved from simpler beings. But it is silly to even compare humans to any other animal. We are different. Completely different. Incomparably different. That seems blindingly obvious to most people, and it is not merely a convenient story we use to justify eating animals.

Isn’t it a bit silly to think that the death of a fully conscious human adult is even comparable with the death of any other animal? Aren’t they tragedies of a different type, rather than just being different locations on the same scale? To me, and I suspect most people, that is intuitive. The death of a human is the death of an entire universe. The death of a cow is, well, the death of a cow.

entirelyuseless

Oct 24 2016 at 1:35am

austrartsua is correct here. The thing that is weird about Huemer’s argument is that he not only takes it for granted, but assumes without question that 1) morality is not based on humans (which it is), and 2) a human being is not a kind of thing, but just something which differs in various degrees in various respects from other animals. The second point is more debatable, but Huemer assumes it without even discussing it. And it is perfectly obvious because of (1) that a human being is a kind of thing in the way that matters, namely relative to morality.

brad

Oct 24 2016 at 3:36am

“What about killing animals for food because the meat of chickens, pigs, cattle, etc., is a relatively inexpensive source of protein? ”

It’s not though. It is a relatively expensive form of protein.

Only chicken comes close in cost per gram of protein to the best vegan sources.

Taste is why we eat animals.

Miguel Madeira

Oct 24 2016 at 5:42am

“Yes, humans are animals who evolved from simpler beings. But it is silly to even compare humans to any other animal. We are different. Completely different. Incomparably different.”

There is much more similarities between a cow and a human than between a cow and, let’s say, a jellyfish (both humans and cows have brains, for example).

IGYT

Oct 24 2016 at 7:18am

I think it just wrong that that the distance between Einstein and Average Human is something like half that between Average Human and Cow. Granted, we cannot actually measure Cow IQ. I rather doubt there is anything meaningful to measure. But if there is, my intuition is that if the distance from Cow to Average Human fits on my computer screen, the dots for Einstein and Average Human overlap.

I do not claim my intuition is superior to Huemer’s. But unless he can supply some reason why mine is unreasonable, his “features (i) and (ii)” are entirely artifacts of his arbitrary sense of how we should scale intelligence.

Denver

Oct 24 2016 at 7:35am

What would happen if you sat a bug and a cow down and gave them an standard IQ test? Would the cow score higher?

Probably not. The cow might eat the paper the test is written on, the bug would likely fly away. Neither animal would score anything, because neither animal has the mental capable to communicate. Nor ever will.

So I think Huemer’s graph is a little disingenuous. He’s trying to show that Bryan is choosing some arbitrary point in IQ for having an ethical consideration for pain. But that point is neither arbitrary, nor is it clear that it’s even non-linear. In terms of communication, cow’s are better than bugs, but only marginally.

And if you don’t think that communication is the differentiating factor between a moral consideration for pain or not, think of a situation in which a human cannot, and will never be able to, communicate. He is literally a vegetable on the table. Is it an absolute moral truth that he should not be left to die? If so, then do you not see pulling the plug on comatose patients as murder?

Miguel Madeira

Oct 24 2016 at 11:15am

“Neither animal would score anything, because neither animal has the mental capable to communicate.”

Bugs and cows can’t communicate with humans, but humans also can’t communicate with bugs and cows (humans and social insect could communicate with animals of the same species, specially if they are from the same culture or colony; being a social animal, I imagine that cows could also communicate with other cows).

Miguel Madeira

Oct 24 2016 at 11:21am

About intra-species communication, we have dogs (who, unlike wolfs, can understand human non-verbal communication),honeyguides, killer whales, and perhaps dolphins and chimps.

gwern

Oct 24 2016 at 1:10pm

I don’t see how that follows. Someone like Einstein is almost identical in intelligence to a random human being, compared to a cow or a grasshopper. You can see this in the extreme ordinariness of his neuroanatomical properties, where he has about the same number of neurons and global connectivity and brain weight etc as any other human (with just some relatively small differences in glial cells and the hippocampus, IIRC, which may just be chance), which is extremely different from comparing any human’s brain with that of a chimpanzee where the difference is measured more in kilograms and billions; brain size correlates with intelligence but within fairly narrow limits of total volume and brain imaging studies still struggle to come up with neurocorrelates of intelligence like white matter integrity and predict differences; you can see this narrowness in the close similarity of human cognitive performance on tests with cardinal scales like reaction time or backwards digit span (average person has a digit span of ~4 with an SD of ~1, so even a genius would be predicted to have hardly any more WM than everyone else, rather than, say, a digit span of hundreds); or considering the genetic basis of intelligence, the high polygenicity and small effect sizes implies that a genius like von Neumann is benefiting from perhaps scores more beneficial alleles on net – out of *thousands* of alleles – than everyone else. We see a vastly wider range comparing grasshoppers to chimpanzees, or chimpanzees to humans; consider the range of computational capability between your smartphone and a supercomputer (to give a recent example, it would take a smartphone days or weeks to train an neural net to beat Pong, while using 1000+ cores on a supercomputer can solve it in under 4 minutes – now that’s a ‘very smart’ computer compared to the smartphone!). Since Einstein is much like you or I, why would he get any intrinsic weighting as ‘vastly more important’ in the first place? And since he doesn’t get such a huge weighting, it hardly constitutes reductio ad absurdum.

Denver

Oct 24 2016 at 2:39pm

@ Miguel

“Bugs and cows can’t communicate with humans, but humans also can’t communicate with bugs and cows”

Part of what I’m trying to get across is that consideration towards one’s pain is, at least to some extent, due to one’s ability to communicate sentience. If it turned out all cows were philosophical zombies, then I think it would be hard for anyone to argue that we should care if cows suffer. Cows can’t communicate sentience, so I have little reason to assume that a cows suffering is of greater importance than my pleasure when eating steak. Humans can at least talk and respect another’s rights, which isn’t itself conclusive proof of sentience, but it’s a lot better than what a cow can do.

“About intra-species communication, we have dogs (who, unlike wolfs, can understand human non-verbal communication),honeyguides, killer whales, and perhaps dolphins and chimps.”

I agree that harming dogs is wrong. Not as wrong as harming a human, but more so than harming a cow.

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 24 2016 at 2:56pm

You’re just swapping the label of the horizontal axis. For each approximate level of cognitive sophistication, you plot a data point of approximate badness. And behold, you will have your own very similar upward-sloping graph. How do you decide where exactly to draw the points? You are no better off than Bryan in that regard.

A more promising theory of “pain badness” is simply anthropomorphism – pain is bad relatively to how human-like things are, and their proximity to us. Some animals like dolphins and monkeys are particularly people-like, so inflicting pain feels really bad, and in fact we may want to talk about giving them rights. Dogs live in our homes and have lots of human-like qualities like happiness and loyalty, so cruelty to dogs is strictly taboo. Cows are big and stupid and live far away, and thus are harder to identify with, so eating them is fine (but killing them humanely is better if possible). Bugs are creepy and gross and also nuisances that spread disease, and can be killed without mercy.

And, anthropomorphism could provide a fitness advantage for things like domesticating animals and hunting, so there is a good explanation as to why it exists. I don’t care whether or not pain is actually “bad”. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. Regardless, I don’t see how that moral fact (if it exists) has influenced the reality we actually live in with regard to how people feel about animals.

Effem

Oct 24 2016 at 3:13pm

@austrartsua

While i tend to agree, this presents a major logical problem. If, by genetic engineering or otherwise, some humans end up with a more advanced form of consciousness that would provide justification to exterminate the rest of us.

BC

Oct 24 2016 at 5:51pm

The intra-species gap, along both axes, is infinitesimally smaller than the inter-species gap in Huemer’s graph. This is not a reflection of any pro-human bias because I would make the same statement about all non-human species. For example, the variation across monkeys is much smaller than the gap between monkeys and cows. Huemer’s graph is also missing a lot of species between cows and humans. There are “intelligent” non-extinct species like monkeys, whales, and dolphins as well as extinct hominids like Neanderthals, Homo habilis, etc. Including these would make it unnecessary to include a big nonlinearity just below humans. We might very well believe that Neanderthals should not be kept under factory-farm conditions, if they were still around. Cows and chickens are far away from Neanderthals though. To be fair, Caplan’s original argument that we can draw inferences from animal rights activists’ treatment of bugs may also be off. There is a large gap between bugs and cows. It’s hard to compare that gap with the also large gap between cows and humans.

As far as how I would expect super-intelligent aliens to treat us, I would hope they would respect our rights and treat us morally *as we understand the concepts of rights and morality*. If their super-intelligence allows them to understand a higher notion of say super-rights or super-morality that *we aren’t even capable of understanding*, then I wouldn’t necessarily expect them to extend those super-rights to us. For example, if a human falls from a tree and feels pain as a result of breaking an arm, we don’t consider gravity or nature to have immorally caused pain, so we don’t find all pain to be immoral. I wouldn’t necessarily expect super-aliens to “use gravity” more super-morally towards us, if we aren’t even capable of understanding what that means, even if they do use gravity super-morally towards themselves. As far as we know, a cow may be incapable of even distinguishing between what we would call pain caused by nature vs. pain immorally caused by another human. Such comprehension requires understanding concepts like causality, natural vs. unnatural, moral vs. immoral, and free-will. If a bull inflicts pain on a bullfighter, for example, we don’t think that the bull acted immorally because we don’t even believe that the bull understands morality. (We may try to stop the bull, but we don’t think the bull is immoral.) Cows may severely dislike pain, but they may not believe that we are immorally inflicting pain on them, just like we may not like falling from trees but do not believe that nature or God is super-immorally imposing gravity on us because we don’t even understand what super-morality is.

James

Oct 24 2016 at 8:54pm

So far, it looks like this difference of belief arises entirely from different simplifying assumptions, rather than an actual disagreement about moral facts. I can’t believe either Caplan or Huemer seriously believe there exists a real (in the sense of moral realism) function with a domain and a range and units and dimensions, etc. which characterizes the relationship of the suffering of various organisms and the badness of that suffering.

Such a function, so long as it is everywhere increasing in IQ, would imply that there are possible scenarios in which it is not just morally permissible but also morally compulsory for human authorities to surrender the entire human race to suffer for the purposes of sufficiently intelligent aliens. This is far more contrary to commonsense moral intuition than anything either Caplan or Huemer has said so far about animals and bugs.

David Friedman

Oct 25 2016 at 11:09am

Huemer’s point about the shape of the curve assumes that there is an obvious metric for IQ. It makes some sense to consider IQ in the sense of ratio of mental age to physical age in humans as cardinal. But that doesn’t even work for humans once you get above the IQ of a random adult, since someone of eighty isn’t four times as smart, isn’t even smarter, than the same person at twenty. The claim that a human has a higher IQ than an ant makes some sense but what does it mean to say that the human IQ is (or isn’t) a million times that of the ant?

“We are different. Completely different. Incomparably different.”

For evidence against that claim I recommend Chimpanzee Politics, a detailed account of lengthy observations of a group of chimps. The chimps come across more like stupid humans than smart insects.

Effem

Oct 25 2016 at 12:34pm

This analysis raises a few other thorny questions:

1) Where do unborn humans fall on the scale (presumably below cows)?

2) What if we were to devise a painless way of killing animals, does that change the conclusions?

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 25 2016 at 2:03pm

@Effem:

(channeling intuitionists)

1) The relevant non-moral fact is whether or not an unborn human consciously experiences pain or not. This would determine just how bad it is to cause pain to unborn humans. In general, there is widespread moral agreement that pain is bad, so all things being equal we prefer solutions that minimize pain to others – humans or animals. This includes scenarios like executing convicted murders who we have concluded don’t even have a right to life, yet have a right to die in non-cruel and usual ways.

2) Pain causing should be considered separately from killing. To be clear, we all know that inflicting pain is bad, and unjustified killing is bad – but sometimes they are necessary! What is debatable are the non-moral consequences of such things. Maybe eating animals is justified to provide enough quality food for the human population. But if scientists were able to grow vat-meat that was a drop-in replacement for factory farmed meat (nutrition, tastes, etc), then we would all obviously switch over.

Kris

Oct 25 2016 at 5:34pm

I think that it’s more helpful to look at concrete hypotheticals rather than the shape of the above graph. (Although I do agree that Bryan’s theory does seem pretty self serving.)

So.

Would you think that torturing a cat for fun is acceptable behavior?

If your kid said to you “I’m gonna spend the weekend electrocuting the cat we found on the street with my friends, it’s going to be a ton of fun” would you be horrified? Or would you think that it’s just another morally irrelevant preference, like watching a movie?

Speaking of which is, say, dog-fighting an acceptable past time behavior?

Or, take the case of babies. You could argue they’re less intelligent than a cow. Why not torture them? If you say it will impact them later on, let’s modify the thought experiment. Suppose we have reliable medical evidence that a newborn will die before the age of 2. Thus, it will never be “intelligent” in the broad sense of the word. Is it okay to torture it? If not, why not?

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 25 2016 at 9:39pm

Kris, what has Michael said that would lead you to believe that he thinks torturing cats or babies is acceptable? He’s pretty clear that he thinks that causing pain to creates in lower states of consciousness is unacceptable

Kris

Oct 26 2016 at 1:33am

Benjamin, sorry, I wasn’t clear. I wasn’t addressing Michael. Just the general reader.

Benjamin R Kennedy

Oct 26 2016 at 10:16am

@Kris – here is skeptic’s answer:

This is a false dichotomy. I can be horrified by this behavior without affirming that there is a cosmic rule that I ought to be horrified. This rule looks like “torturing animals is wrong”. Torturing animals isn’t wrong or right or anything – I just know that I find it horrifying and I’d prefer a world with less of it.

You can take any moral framework that people devise, and it is fairly easy to devise an edge case hypothetical that “breaks” the system. This is because humans evolved moral thinking to survive in friendly small packs and interact with rival communities, not to save the world from ticking time bombs by torturing someone or deal with the complexity of creating human life in labs, or any of that kind of stuff where there is no real agreement.

Comments are closed.