A number of friends on Facebook have been discussing whether the federal tax system is “progressive.” That word has emotive content–“progressive” seems good–but all it means is that the higher your income, the higher your tax rate.

One economist friend argued that bringing in the Social Security tax (FICA) and the Medicare tax (HI) makes the system less progressive than otherwise. That’s absolutely true for Social Security. The tax rate for Social Security is a flat 12.4% (6.2% for employer and employee each) for earnings up to $127,200 and zero thereafter. (In 2018, the threshold will be $128,400.) It’s probably true for Medicare. One factor makes the Medicare (HI) tax a regressive tax and one factor makes it progressive. I don’t know which dominates. The factor that makes it regressive is that the tax is just on earnings and higher-income people have a higher percent of their income that is not classified as earnings–dividends, interest, rents, royalties, and capital gains, to name five. The factor that makes it progressive is that Obamacare added 0.9 percentage point to the HI tax for individuals making more than $200,000 and for married couples filing jointly making more than $250,000.

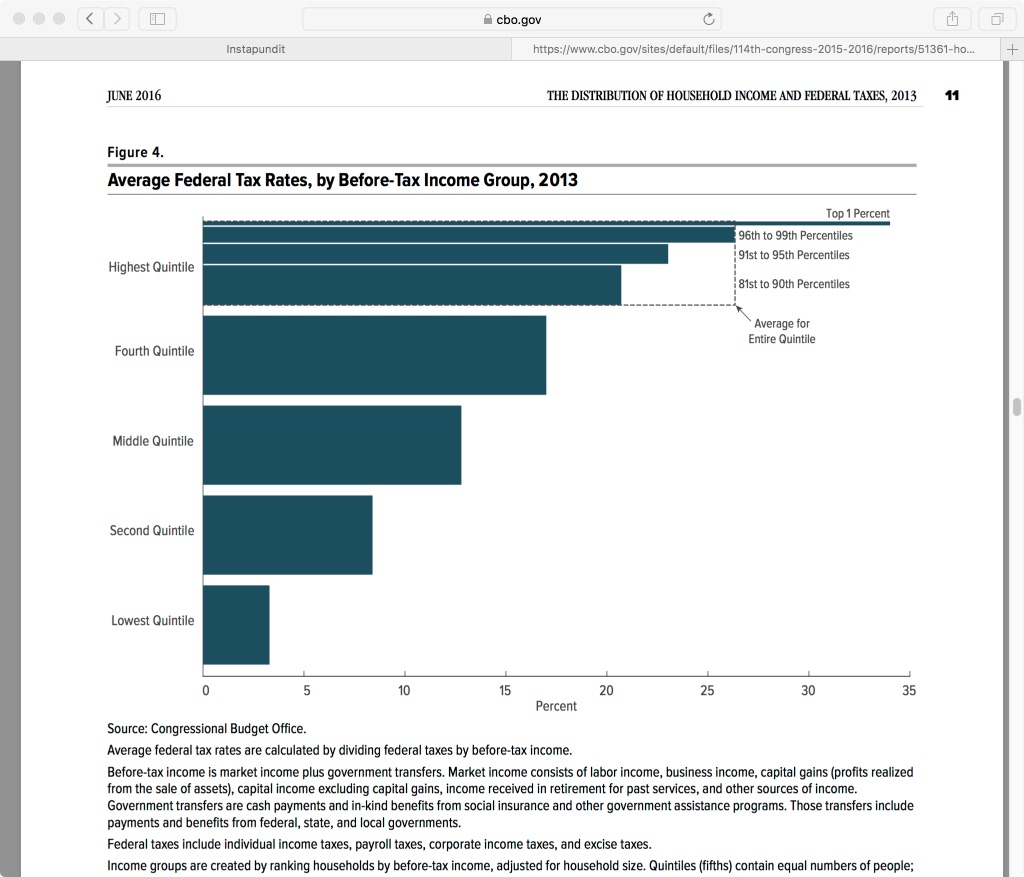

The net effect of all federal taxes is that the higher your income, the higher your average tax rate. (The CBO produced the graph below–see its Figure 4 on page 11.)

Of course, we can’t simply look at whom the tax is imposed on to know who bears the burden. It is a virtual certainty, for example, that some of the corporate income tax burden is borne by workers. This means, of course, that the cut in corporate income tax will help workers. We use the term “tax incidence” to describe who bears the burden of a particular tax.

In the study from which the figure above is taken, here’s the CBO’s explanation of how it allocated tax incidence. As it makes clear, these are assumptions. They may not be true.

CBO allocated individual income taxes and the employee’s share of payroll taxes to the households paying those taxes directly. The agency also allocated the employer’s share of payroll taxes to employees because employers appear to pass on their share of payroll taxes to employees by paying lower wages than they would otherwise pay. Therefore, CBO also added the employer’s share of payroll taxes to households’ earnings when calculating before-tax income.

CBO allocated excise taxes to households according to their consumption of taxed goods and services (such as gasoline, tobacco, and alcohol). Excise taxes on intermediate goods, which are paid by businesses, were attributed to households in proportion to their overall consumption. CBO assumed that each household’s spending on taxed goods and services was the same as that reported in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey for a household with comparable income and other characteristics.

Far less consensus exists about how to allocate corporate income taxes (and taxes on capital income generally). In this analysis, CBO allocated 75 percent of corporate income taxes to owners of capital in proportion to their income from interest, dividends, rents, and adjusted capital gains; the adjustment smooths out large year-to-year variations in actual realized gains by scaling them to an estimate of their long-term historical level given the size of the economy and the tax rate that applies to them. CBO allocated the remaining 25 percent of corporate income taxes to workers in proportion to their labor income.

My gut feel is that the allocation of 25 percent of corporate income taxes to workers is too low. But it’s only a gut feel.

READER COMMENTS

Austin

Dec 6 2017 at 8:09pm

For the Medicare tax you’re forgetting about the Net Investment Income Tax. At 3.8% it’s actually slightly higher than what the Medicare tax would have be on earned income.

There is still a bit of a gap before it kicks in, where you can be “rich” and not pay it.

Bill

Dec 6 2017 at 9:57pm

Here’s the link to the CBO report:

https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/51361-householdincomefedtaxesonecol.pdf

David R. Henderson

Dec 6 2017 at 10:27pm

Thanks, Bill. I forgot to put in the link. It’s there now.

Michael

Dec 7 2017 at 6:31am

What about the “progressivity” of the Social Security BENEFIT, both in the diminishing nature of the earned benefit formula itself as wages rise (up to the cap), and the fact that the benefit is progressively subject to more income tax at higher income tax levels at the back end? What a double whammy for the so-called rich – FICA taxes are subject to income tax (there is no individual deduction for FICA withheld or paid), and then when you later “get it back” in the form of a benefit check, it’s subject to income tax again (beyond just the “appreciation” piece)! The higher your effective tax rate at the beginning and/or the end, the bigger the double-whammy.

Proof positive that it is not a mechanism for forced saving for your retirement, but a giant redistribution racket. “Trust fund” schmust fund.

Ben

Dec 7 2017 at 6:33am

“My gut feel is that the allocation of 25 percent of corporate income taxes to workers is too low. But it’s only a gut feel.”

The problem for the economics discipline of painful partisanship aptly demonstrated in one sentence.

Brandon Berg

Dec 7 2017 at 7:06am

The incidence of the corporate income tax is more complicated than just x% to labor and y% to capital.

Recall that the partial incidence on labor and reduced incidence on capital are mediated by the higher tax rates causing investors to shift investment overseas. This also has effects overseas, where wages are increased and returns to investment are decreased by the capital escaping the country which increased taxes.

Consider a two-country model with capital mobility. When country A imposes a corporate income tax, this leads to shifting of capital from country A to country B. In other words, A’s K/L decreases and B’s K/L increases. This means that wages decrease in A and increase in B, and pre-tax returns to capital increase in A and decrease in B.

Of course, the increase in pre-tax returns in A is more than offset by the tax increase, so post-tax returns decrease in both countries. Thus, perhaps surprisingly, the incidence of a corporate income tax levied on investments in any one economy is borne by investors globally, regardless of where they’ve invested, whereas the loss to workers in A are gains to workers in B.

If both countries levy the same corporate income tax, then there’s no shift in capital, and in the short run no effect on wages, leaving 100% of the incidence on capital. In the long run, of course, workers are harmed in other ways.

If you’re looking at changing the US’s corporate income tax in isolation, then it may make sense to look just at the domestic effects and ignore most of the above. On the other hand, if we’re looking at tax burden in general, it makes sense to take into account the effects that other country’s corporate income taxes have on US workers (higher wages that partially undo the wage-suppressing effect of US corporate income taxes) and investors (lower pre-tax returns). Taking that into account, 25% may actually be too high.

Brandon Berg

Dec 7 2017 at 7:08am

See William Randolph’s International Burdens of the Corporate Income Tax for an elaboration on the model described above.

Alan Goldhammer

Dec 7 2017 at 8:45am

TR Reid, author of a fine book on tax policy that came out earlier this year, had a nice piece in the Washington Post in mid-November (I don’t think it ever appeared in the print edition which is too bad). He argues that it would be best to zero out the corporate tax as its contribution to overall Federal revenues is shrinking. A good New York Times review of the tax book, “A Fine Mess: A Global Quest for a Simpler, Fairer, and More Efficient Tax System” is worth reading.

One point worth mentioning about Social Security taxes is that they are capped. When I was still working I remember always celebrating when I reached the cap as it always meant more money in my paycheck. Of course removing that cap would go a decent way towards extending solvency of the trust fund.

bill

Dec 7 2017 at 8:56am

@Michael is absolutely correct. The Social Security benefit is very progressive. Personally, I think that’s a good thing. Those taxes should be considered separately because they are tied to a particular benefit, and the benefit increases the more a worker contributes to Social Security. The Left is forgetting what FDR said: “We put those pay roll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and their unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program. Those taxes aren’t a matter of economics, they’re straight politics.” If the Left ever succeeds in breaking the link between the contributions and benefits, it won’t be long and the benefits get cut.

A

Dec 7 2017 at 9:49am

Is there a reason economists judge the progressiveness of tax systems by revenue? Intuitively, it seems like net transfers are more indicative. Is that too logistically complicated to measure, or is there a conceptual reason for the practice?

Bill

Dec 7 2017 at 10:56am

A, is this what you have in mind?

https://taxfoundation.org/accounting-what-families-pay-taxes-and-what-they-receive-government-spending-0/

David R Henderson

Dec 7 2017 at 11:37am

@Michael,

What about the “progressivity” of the Social Security BENEFIT, both in the diminishing nature of the earned benefit formula itself as wages rise (up to the cap), and the fact that the benefit is progressively subject to more income tax at higher income tax levels at the back end? What a double whammy for the so-called rich – FICA taxes are subject to income tax (there is no individual deduction for FICA withheld or paid), and then when you later “get it back” in the form of a benefit check, it’s subject to income tax again (beyond just the “appreciation” piece)! The higher your effective tax rate at the beginning and/or the end, the bigger the double-whammy.

Very good point.

There are two strong factors in the other direction, though. First, higher-income people tend to have more formal education and so start to pay substantial Social Security taxes much later than the less-formally educated: in their early to mid-20s as opposed to late teens. These amounts are small for the first few years in either case because taxed wages and salaries are low. But the compound interest effect is huge.

The second factor is that higher-income people tend to live longer and so they get the payments longer. Milton Friedman, in a famous debate on Social Security with Wilbur Cohen, made this argument and speculated that this effect dominated, making the Social Security system on net not progressive. I think he went too far, but that’s only my gut feel, as it was his. He didn’t have solid data.

@Ben,

The problem for the economics discipline of painful partisanship aptly demonstrated in one sentence.

So I guess Ben would suggest that either (1) I not have gut feels, which I think is impossible, or, (2) that I not tell people I have them.

David R Henderson

Dec 7 2017 at 11:50am

@A,

Is there a reason economists judge the progressiveness of tax systems by revenue?

The main reason, which you might not judge to be good, is that it’s easier. It’s the old “looking for one’s keys under the lamp post because that’s where the light is better” reason.

Intuitively, it seems like net transfers are more indicative.

Your intuition is correct.

Is that too logistically complicated to measure, or is there a conceptual reason for the practice?

The conceptual reason is what’s behind why it’s often too complicated. The reason is that transfers are not just clean transfers. You often have to do something to get them. Take Medicaid, one of the best examples. A standard way to measure the transfer to poor people from Medicaid is to estimate how much Medicaid spends on poor people as a group. That’s very easy. But poor people don’t get the Medicaid transfer as a subsidy that they can choose whether to spend on medical care or on something else. It is all spent on medical care. Recent evidence shows–I don’t recall the source offhand–that poor people value $1 of Medicaid spending on them at approximately 25 cents (if I recall correctly.) So estimating the $1 as $1 of transfer badly overstates the transfer to poor people.

Also, how do you handle defense spending? Higher-income people are typically richer than lower-income people and, so, have more to defend. But very little of the DoD budget is spent on defense. Most of it is spent on offense. How high a value do people, high-income or low-income, put on that? We have very little idea. Let’s go back and look under the lamp post. 🙂

Also, here’s bill’s link in his response to you.

David R Henderson

Dec 7 2017 at 11:51am

@Brandon Berg,

I’m answering you separately because you raise a good point that I need to think about and don’t have time to think about this morning. Will do so later today or tomorrow.

robc

Dec 7 2017 at 12:08pm

@bill,

SCOTUS has already ruled their is no connection between contributions and benefits.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flemming_v._Nestor

jc

Dec 7 2017 at 12:41pm

Just for kicks, oldie-but-goodie: OECD measure of tax progressivity of various countries.

(Counts income and employee paid payroll tax. Doesn’t include other taxes like VAT, which would have obvious effects on the progressivity of tax systems overall. Doesn’t include the whole world, of course, e.g., some claim South Africa is actually the most progressive country.)

https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/-4QJRukHrJ5c/TYhks_W3tFI/AAAAAAAABOU/tpmi4_tRNIQ/s1600/taxburden.jpg

[ broken HTML fixed—Econlib Ed.]

bill

Dec 7 2017 at 1:09pm

@robc,

I believe that you are correct on the law (I’ll check out the link). However, I think FDR got the politics right. When future tinkering happens, if any current benefits are cut, or if future benefit cuts go beyond some sort of “freeze” or CPI changes then I will concede that I was mistaken. IMO, future changes will be mostly on the revenue side.

Michael

Dec 7 2017 at 3:27pm

Thanks David. You mention compound interest; I read somewhere that the internal rate of return implicit in the Social Security benefit is something around 0.5% of contributions for higher earners. It’s a terrible “investment” for such people:

http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10923.pdf

The benefit formula for Social Security is highly progressive. The lower your average earnings, the higher a benefit you get relative to your contribution.

Floccina

Dec 7 2017 at 3:59pm

If FICA is a tax, rather than forced savings, then why does SS pay out more to higher earners? The people who want to bring FICA into a tax discussion often do not want to change the payout to be the same to all retirees (IE $200/week to each US citizen over 67). When you want to change the program at all they shout we paid into it. IMO paid into it is different than taxed. Taxes we all pay go into SNAP and TANF but few of us complain about not getting SNAP and TANF.

Justin D

Dec 9 2017 at 1:42am

–“If FICA is a tax, rather than forced savings, then why does SS pay out more to higher earners?”–

Because the benefits are structured that way. I think of SS as essentially a public pension.

–“The people who want to bring FICA into a tax discussion often do not want to change the payout to be the same to all retirees (IE $200/week to each US citizen over 67).”–

Of course not. $200/wk is way below the poverty line and well below what almost everyone is expecting and planning their retirements around.

–“When you want to change the program at all they shout we paid into it. IMO paid into it is different than taxed.”–

That’s just effective marketing. FICA payments truly are just taxes, and SS payments are just government transfers.

–“Taxes we all pay go into SNAP and TANF but few of us complain about not getting SNAP and TANF.”–

Well sure, but then the government never promised to provide such to us unless we qualified, whereas it has promised that every worker who paid FICA taxes would receive a benefit corresponding to his or her income in retirement, and many people structure their financial planning around that promise. And many would complain if they needed SNAP benefits and found the program was canceled or cut.

Comments are closed.