While working on a principles of economics textbook, I began wondering how students evaluate terms like “consumer welfare”. Who are these consumers?

There’s a term for people who are not consumers, they are called “corpses”. All living people are consumers. So any policy that benefits consumers as a group also must, ipso facto, benefit society as a whole. Right?

Not quite, as that’s not what economists mean by ‘consumers’. We are not talking about a distinct set of people (all people are consumers); we are talking about one aspect of our lives. Thus a policy like price controls affects both consumers and producers, and hence everybody, both in our role as consumers and in our role as producers.

[You may object that we are not all producers. But those who are not, such as children and people on welfare, base their consumption on the monetary contributions of people who are producers. So in a deeper sense we all have a stake in both the consumption and production side of the economy.]

I’m probably too close to all of this to know whether these points are obvious, so I’d be interested in your take.

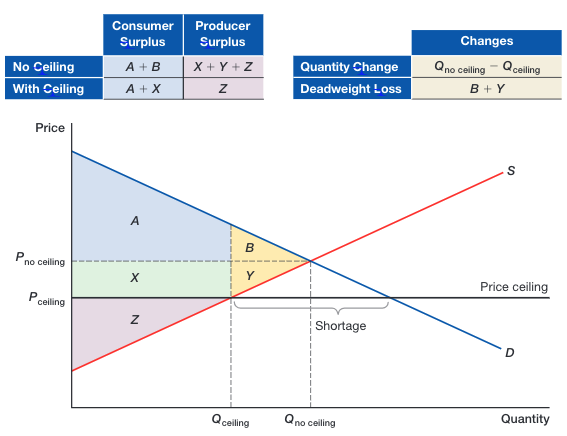

Let’s consider a specific example. Suppose we adopt across-the-board price controls, as in 1971. You can show the impact on “consumers” and “producers” with a supply and demand diagram:

In this graph, it looks like “consumers” might gain from price controls. But this doesn’t mean that there is some segment of society that actually gains from price controls, rather that people might gain in their role as consumers, lose in the role as producers, and lose overall due to the decline in “total surplus” (due to the deadweight loss.)

[As an aside, even consumers qua consumers might not be better off due to queuing costs.]

I wonder if students reading these textbooks think “Gee, I’m a consumer, so I better pay close attention to the effects of government policies on consumers.” If so, they are missing the bigger picture. Students should be focused on the effects of government policies on total surplus, as consumer and producer surplus are just a subset of each and every person’s interest is in both sides of a market.

I’d even apply this to individual product markets. It’s true that consumers and producers of automobiles might be very different people, but many of the policies that affect individual markets are widely applied. If you are considering the wisdom of trade barriers, it probably makes more sense to think of barriers affecting a wide range of products, as they are unlikely to only be imposed on a single good. Thus if you think to yourself, “I’m a car producer, thus I like tariffs”, beware that the tariffs don’t end up being imposed on steel and aluminum, for which you are a consumer. Indeed there’s a good chance that this is exactly what will happen in the near future, hurting the auto industry, and indeed hurting most of American manufacturing.

READER COMMENTS

Rajat

Jan 20 2018 at 7:49pm

In the electricity market (where I work), large commercial customers and politicians often call for reductions in regulated (natural monopoly) network tariffs to benefit consumers, even though lower tariffs – to the extent they compromise cost recovery – will tend to deter investment in the grid. Similarly, people will call for bigger (regulated) interstate transmission links that lower wholesale prices in importing states (and overall given supply curves that generally go from flat to very steep), even where the increased surpluses may not outweigh the cost of building the larger links (ie they don’t pass a cost-benefit test), because consumers will see lower prices while electricity generators effectively bear the loss at least in the short run. To the extent markets currently exhibit market power and this can be permanently addressed through such interventions, there may be a durable benefit to consumers from net detrimental projects, but that is the question.

tOKEN

Jan 20 2018 at 7:54pm

The FTC and DOJ, in their approach to merger review, generally look at the impact of the merger on consumer surplus. It is not generally sufficient for the companies to show that benefits to their shareholders from the merger outweigh the damage to consumer welfare.

Thomas Sewell

Jan 20 2018 at 7:58pm

I understand and agree with the theory described.

In terms of clarity and mental blindness, you may be too used to reading supply/demand graphs and thus not realize how dense with information this is even when you previously understand the associated theory. I imagine it’d be worse for someone who is just learning the theory behind it.

A couple of suggestions:

S = Supply and D = Demand. Obvious, until you consider you’ve got two “Surplus” values in the header (which people will naturally look at to understand the graph) and nothing mentioning Supply.

It’s not obvious to me either from the graph or your explanation as to why the Shortage measurement is taken from where the demand crosses the price ceiling rather than where it crosses the “no ceiling” dashed line. That choice may bear further explanation in the associated text.

It would be nice if more people wearing their “voter” and “politician” hats understood all this. 🙂

Rajat

Jan 20 2018 at 8:02pm

To anticipate a possible response, many people don’t identify with the network businesses or generators they wish to extract value from. State governments (here in Australia) have mostly privatised their electricity businesses and many networks and generators are foreign-owned. Although the remainder are largely owned by pension funds, people still see favourable distributional impacts from such extraction, because richer people have more money in their (private) pension accounts. Obviously, rich people tend to consume more electricity as well, although often not proportionately more.

Of course, we’re talking about a world and a country where most people – including many economists who write in newspapers and are active on social media – don’t accept that corporate tax cuts benefit workers. So what can one expect…

Pierre Lemieux

Jan 20 2018 at 8:24pm

An interesting question, it seems to me, is to which extent producer surplus is not an artifact of partial-equilibrium analysis. The only reason producers like their producer surplus on market A is that they can use it to purchase goods and get a consumer surplus on market B. As we produce in order to consume and not the other way around, it seems that producer surplus disappears in the whole economy. Look at it in general-equilibrium context: along the n-dimensional contract-curve for the whole economy, there is no producer surplus. Moreover (and that’s a different point), over the long run, when all factors of production are variable (when Baudelaire and Leonard Cohen have been replaced by other poets), producer surplus may disappear even in a single market. (I am also interested in comments on these reflections.)

Matthew Waters

Jan 20 2018 at 9:15pm

Rajat,

I’ve worked for commercial electricity consumers in regulated and deregulated markets. I’ll admit to not working deep with tariffs and IRP process, but my experience has made me very critical of regulated generation.

If the transmission is truly overinvestment, then a private company risks losses. With airlines, overinvestment was so endemic several bankruptcies happened. After such overinvestment, there is no good solution except wait for enough depreciation until new investment makes sense.

Both PUCs and FERC have ROE on new investment which is still too high. ROE > actual cost of equity means *current* owners dilute their shares less than the profit increases.

In terms of *total* surplus, such regulatory capture is to get some of the possible monopolistic rents from the natural monopoly. It increases producer’s surplus, but reduces total surplus.

(Also, sorry for the inside baseball to everyone else. I don’t know if anyone else would be as interested in utility pricing and surpluses.)

Alec Fahrin

Jan 21 2018 at 1:40am

I am definitely out of my league on this issue, but maybe I can expand the logic in this post to the global economy.

In the globalized world, and especially the future world, economic (and social) trouble in one country will at least indirectly cause negative effects in other countries.

For example, price controls in Venezuela caused an economic meltdown in that nation. Most importantly though, the oil industry fell apart. If Venezuela just maintained its 2008 oil production level, oil prices worldwide would be 5-10% cheaper. Compound that by 10 years now and the entire world ended up paying about $1.5 trillion more than necessary.

Yes, certainly some nations benefited in a short-term relative sense from Venezuela’s collapse (and Libya’s), but in the long-term we all pay for mistakes either directly or indirectly.

This is why the WTO (and the global trade it boosted) is probably the biggest net benefit to humanity since the advent of anti-biotics.

Actions that benefit foreign nations can benefit your own, sometimes even more. Meanwhile actions that harm foreign nations because you dislike their competition may eventually come back to haunt you. Not just through direct deadweight costs, but through second-order indirect costs.

And yet, I constantly see people cheering on others’ misery.

Thaomas

Jan 21 2018 at 9:26am

@ Alec Fahrin

Colombia benefitted from a large influx of Venezuelans, many of them skilled professionals, but by less than the costs (measured against pre-meltdown) to the people who immigrated.

The US cold have benefitted more (some Venezuelans did arrive), but our immigration system is not flexible enough to take advantage of opportunities like Venezuela, Syria, and soon I’m afraid of South Africa.

Alec Fahrin

Jan 21 2018 at 1:22pm

Thaomas,

And yet, did we not lose out from the collapsed oil production? We still consume more oil than we produce, so that’s a huge cost over the last decade.

Considering the U.S. consumes 22% of world oil, we lost about $250 billion over the last decade (rough measure) because of Venezuela’s collapse.

Taking in the Venezuelan brain drain might be a short-term benefit for Colombia, but losing a $350 billion economy is probably worse for humanity as a whole.

Rajat

Jan 21 2018 at 8:00pm

Matthew, I wasn’t seeking to debate the actual appropriateness of the level of regulated return provided to transmission networks (for a start, I’m in Australia). My point was that often those calling for lower tariffs assume that it won’t have long-term consequences for investment and efficiency. Yet these are often the same people who want over-investment in the grid to lower wholesale energy prices. In both cases, producers are seen as foreigners or fat-cats that will not change their behaviour even if they earn less.

TallDave

Jan 22 2018 at 2:23pm

I’d say “total surplus” is where economics become non-obvious.

Alec — the US is actually now a net exporter of petroleum (we import, refine, and then export). Venezuela’s chronic underinvestment in oil production makes oil prices higher for consumers everywhere, but only until marginal rigs become active elsewhere to push prices down again (esp. in the US, where oil production is probably most sensitive to price). The aggregate effect on the US is therefore probably pretty small, a few billion at most.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=oil_imports

Philo

Jan 22 2018 at 3:37pm

@ Pierre Lemieux:

Consumer’s no less than producer’s surplus is “an artifact of partial-equilibrium analysis.” And does anyone *like* or *value* his surplus of either kind? Do I feel the better about my purchase of, say, apples than I do about my apparently similar purchase of, say, oranges, due to the fact that my demand-schedule for apples is less elastic than is my demand-schedule for oranges? Apparently Prof. Lemieux thinks I should feel thus, since (ceteris paribus) my consumer’s surplus for the good with the less elastic demand-schedule will be the greater. But I detect no such feeling in me, nor do I see any theoretical reason why it should exist. I would have more to lose from a rise in the price of apples than from a similar rise in the price of oranges, but why is this particular counterfactual observation supposed to evoke any actual feeling of satisfaction or dissatisfaction in me? (It’s also true that I would have more to gain from a decline in the price of oranges than from a decline in the price of apples. But, again, so what?)

Acad Ronin

Jan 22 2018 at 3:58pm

@Pierre Lemieux & @ Philo:

I think we often think in terms of producer and consumer surplus. People do say, “and they pay me to do this”, from which we are to infer that they love what they do and would be willing to do it for less. On the other side, people say, “Look what I got for $5”, from which we may infer that they would have been willing to pay more than $5 for whatever they bought. In both cases, though they may not use the terms, the person making the statement realizes that they are inframarginal.

Procrustes

Jan 22 2018 at 6:27pm

Philo – look at it another way. Say you buy an apple a day but the government slaps on a quota that says you can only have one a week. How much would you be prepared to pay an apple smuggler for the other six apples a week?

OHSBruce

Jan 23 2018 at 5:38pm

Philo –

Another thought. I walk into a store expecting to pay $50 for a shirt, and it’s on sale for $40. Am I happier to pay the lower price? The increase in CS makes me happier with the purchase, and the lower price gives me resources to buy both apples and oranges, each of which makes me happier still. The sudden decrease of price that leads to this extra CS is more dramatic, and thus noticeable – but the principle is the same. When we get CS, we have resources left over that we would have spent that we didn’t need to spend on that good, so we can increase our consumption accordingly for the same amount of resources.

Comments are closed.