On Sunday evening, August 15, 1971, I was soaking in the bathtub with the door open because my roommate, Ron Robinson, was out. At the time I was living in a two-bedroom apartment in Winnipeg and was about to launch the next part of my intellectual odyssey: a move to London, Ontario to study advanced undergrad economics at the University of Western Ontario for a year before going on to graduate school, preferably in “the States.”

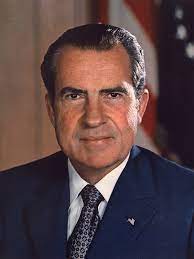

I had the bathroom door open so I could hear the news on the radio. And what I heard appalled me: Nixon had just used executive power given to him by Congress to freeze all wages and prices in the United States for 90 days.

I had understood more than a year earlier why price controls are a bad idea, and my reading economics on my own for 4 hours a day every weekday for the previous year had amplified my understanding.

What I didn’t know–and no one could know–was that the price controls on oil and gasoline would combine with an OPEC-induced increase in the world price of oil in the fall of 1973 (from $3 to $11 per barrel) to cause serious shortages. (The reason no one could know was that we didn’t know that OPEC would have such power in just 2 years and would use it so effectively.)

And that wasn’t the end of it. President Nixon, who had understood the problems with price controls when he worked with the Office of Price Administration during World War II, was too cowardly to reverse what he must have known, and what advisors like George Shultz almost certainly told him.

So not only did we get the standard problems with price controls–lineups, billions of hours wasted in line, misallocation among users, and even occasional violence in line–but also those controls led to many more controls that we are still contending with today.

First, Nixon signed a bill that imposed what the truckers called the “double nickel,” their name for the nationwide 55 mph speed limit. The good news there is that it was finally ended in 1995, so we had to deal with it for “only” 21 years.

Second, that’s how we got the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) law under President Ford. Government officials saw that the artificially low price of gasoline was causing us, in our purchases of cars, to act as if the price of gasoline was artificially low. So, instead of allowing the price controls to end, the feds dictated to auto producers and consumers the average fuel economy that had to be achieved. This has been raised more and more over the years and is one of the main factors in the sale of electric vehicles. The 1975 law also gave the feds power to regulate fuel efficiency of many appliances.

Third, especially under President Carter, the feds started regulating the “energy efficiency” of various appliances. We’re still dealing with the unintended, but largely predictable, bad consequences of those regulations.

Thanks a lot, Dick.

READER COMMENTS

David

Aug 15 2023 at 2:19pm

From a new history, after Nixon doubles down on wage and price controls:

“Nixon worried about Friedman’s move into open antagonism. Shultz was tasked to mollify Friedman, and invited him to the White House for a personal meeting with the president. ‘Don’t blame George,’ Nixon told him. In Friedman’s memory, he offered a zinger in response: ‘I don’t blame George, Mr. President. I blame you.’ No one pointed out there was at least one other man to blame: Arthur Burns.”

David Henderson

Aug 15 2023 at 2:37pm

Thanks, David. That’s one of the parts of Milton’s and Rose’s autobiography, Two Lucky People, that I highlighted in my review.

Andrew_FL

Aug 15 2023 at 5:38pm

Back on the 40th anniversary of Nixon’s announcement, William Walker, who was working in the Nixon Administration at that time, wrote up a nice history of Nixon’s price controls:

https://nixonswageandpricefreeze.wordpress.com/2011/07/14/nixon-wage-and-price-freeze/

Rob Bradley

Aug 16 2023 at 12:05am

Treasury Secretary John Connolly helped persuade Nixon to impose controls i recall.

Jack Yates

Aug 17 2023 at 7:39am

I was at a wake in Brooklyn. Returning to an apartment between afternoon and evening sessions, turned on the TV to see Paul McCracken explaining why they were closing the gold window. The debate about floating exchange rates became very hot thereafter. So, in your view how much did the death of Bretton Woods add to the subsequent inflation including the oil spikes of the ’70s. (I was schedule to take international finance that September with a textbook that lost a lttle something…)

Charlie from Pine Lodge

Aug 17 2023 at 9:40am

We need to teach the economics of Adam Smith and not Karl Marx.

Bubblz

Aug 17 2023 at 12:52pm

I was 8 years old when all of this happened (and had no clue, of course). The main thing I have learned over the decades since is that we are horrendously OVER-GOVERNED, and the out-of-control governance only escalates and increases. When I recently learned that there is a U.S. House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government, I laughed out loud. The Republican Party’s limited-government principle/platform is a highly-selective, narrowly-tailored truth — when it is not an outright LIE, which is most of the time.

Bob

Aug 17 2023 at 5:22pm

I was a grocery clerk during that time. I observed that while prices remained the same, quantities shrunk. Coffee, which was sold in 1-pound cans, slowly went to 14 oz, then 12 oz. They remain at 12 oz to this day. I saw the same thing with many other items.

The Nixon administration asked everyone to report price freeze violations and reducing quantities was a violation. I didn’t rat them out, as that was Stalinesque. I’m sure someone did, but I don’t know if any company paid fines for reducing quantities. I don’t recall any reporting on punishing violations on the nightly news or in the newspapers that I saw.

James Anderson Merritt

Aug 18 2023 at 8:07pm

When I was a kid — upper elementary school age, IIRC — with an allowance of “my own money” to spend, I started noticing two things: Prices of comic books started going up, and the sizes of candy bars started going down, without a change in price. When I started buying comic books, prices had just recently gone up from a dime to twelve cents for a standard-sized issue. The publishers felt compelled to apologize for the two-cent price increases, and published their regrets for several months after the shift. I learned the meaning of the word “inflation” very young in life. 🙂 But not long afterward, I began to notice that my favorite candy bars started being packaged with little cardboard trays inside the wrapping, which, I quickly understood, allowed the manufacturers to fill the packages with a smaller bar, which wasn’t immediately evident until you tore the wrapper open to discover that it had been “filled out” by the bracing. Thereafter, I paid attention to increasingly frequent hikes in comic book prices — to 15 cents, 20 cents, and beyond! — and to cycles of candy bar size-shrinkage and package bracing, by which the candy bar companies ratcheted prices up until the “standard” bar finally acquired the price of the former “large” or “jumbo” bar, at which point the cycle would start all over again. By the time I was in high school, I already had quite an education in practical “corner drugstore” economics. What I didn’t understand (and, in fact, was totally unaware of until the “sandwich alloy” coins were introduced in the US), was how the debasement of the coins and paper notes were connected with the situation. I sorted that out in high school.

Bill Conerly

Aug 18 2023 at 1:28pm

I just looked at the Institute for Supply Management’s survey of slow deliveries to manufacturers. The worst year for supply chain performance was . . . 1973! The data I have go back to 1948. (Their copyright restrictions make it hard for non-subscribers to see the history.) The recent problems, in 2021, were mild in comparison.

dennodogg

Aug 19 2023 at 10:52am

I had once read that the Chinese and some European countries had wanted to withdraw their gold that we had been holding for “safekeeping” in our Fed Reserve banks (as a result of WWII Axis actions) from the US back in the early 1970’s. Fearing a “run” on gold that would’ve allegedly cause a world recession, Nixon placated the masses by removing our currency from the gold standard. Maybe that “run” would have been a good thing as we would’ve found out if we really have all that gold that we claim is in “secure vaults” all over the country. What a tangled web these globalists weave.

Comments are closed.