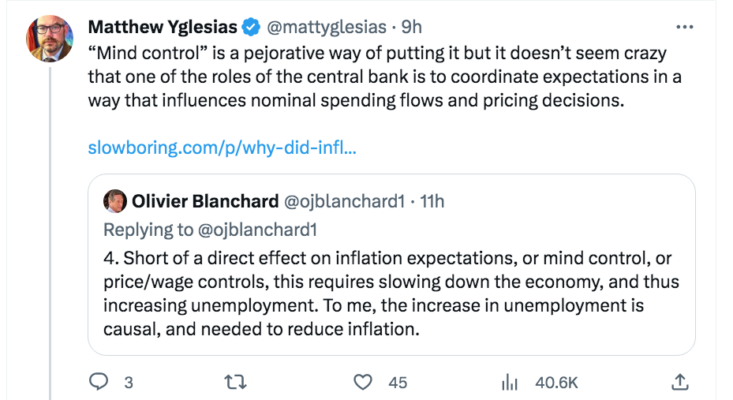

In recent days, there’s been a twitter debate about whether changes in employment drive the inflation process:

I thought of this debate when reading about the sudden rise in the Argentine price level. Here’s Bloomberg:

At shops all across Argentina, from cafes to kitchenware vendors, scores of small-business owners woke up Monday to find some version of the same notice in their inboxes: Their suppliers had hiked prices 20% overnight. . . . Sharp price hikes appeared early for electronics and home appliances Monday. MacStation, an official reseller of imported Apple products in Argentina, raised its computer prices nearly 25% while local e-commerce site Precialo, which tracks pricing history, showed refrigerator, washing machine and TV price tags north of 20% in the past week.

In fairness to Blanchard, prices are more flexible in a high inflation country such as Argentina. But these sorts of countries represent a sort of lab experiment: What happens when you rapidly boost the currency stock in a country not at the zero bound? Or (in this case): What happens when a political shock occurs that leads to faster expected future growth in the money stock? The result is an almost immediate increase in the price level. Yglesias is correct. It’s not “mind control”; it works through the public having a rational forecast of the future path of policy. Argentine citizens have been here before.

I don’t have data on the Argentine labor market, but I doubt that the unemployment rate fell sharply last night. The Phillips curve doesn’t tell us anything useful about the inflation process in Argentina.

In fact, it is monetary policy that drives inflation–not the labor market. In an economy where prices are not sticky, it does so without much change in unemployment. In an economy with sticky prices, unemployment often changes as inflation changes. But that’s an effect, not a cause.

In America, inflation is much lower and prices are stickier. But even here, changes in monetary policy affect nominal GDP growth in a very short period of time, within weeks. The so-called long and variable lags are a myth. Economists have used lags as an excuse for the fact that they use the wrong model. Keynesians use interest rates to indicate the stance of monetary policy, while monetarists rely on the monetary aggregates. Both of these indicators are flawed. When their predictions don’t pan out, they use long and variable lags as an excuse.

If I were trying to make a living as a fortune-teller, I’d say, “After a long and variable period of time, I see you having some health problems.” In the 1960s, it took 10 years for rising interest rates to produce a recession. The interest rate increase of 1994 didn’t lead to recession until 2001.

The best indicator of monetary policy is market forecasts of future NGDP. And monetary policy affects market expectations of future NGDP with no lag at all. When next year’s expected NGDP declines, current NGDP tends to fall after a relatively short period of time. There are no long and variable lags in monetary policy.

Update: Kevin Erdmann points out that our price level might soon be a bit less sticky.

READER COMMENTS

Market Fiscalist

Aug 15 2023 at 7:41pm

I may be thinking about wrongly but:

The CB does stuff to reduce the rate of increase of NGDP

This change must be reflected either in a change in inflation or in output

If prices are sticky it will mostly be reflected in the short run in reduced output

The fall in output is almost certain (again short term) to lead to an increase in unemployment

I’m not getting why the stuff the CB did to reduce the rate of increase of NGDP could not accurately be described a having “caused” the increase in unemployment.

Scott Sumner

Aug 15 2023 at 8:38pm

“I’m not getting why the stuff the CB did to reduce the rate of increase of NGDP could not accurately be described a having “caused” the increase in unemployment.”

It certainly could be described that way. But the rise in unemployment would not be the cause of the lower NGDP. The causation works in the opposite direction.

Market Fiscalist

Aug 15 2023 at 10:14pm

‘But the rise in unemployment would not be the cause of the lower NGDP. The causation works in the opposite direction.’

That was what I was trying to say – that the change in NGDP led to the change in employment.

I thought that in this (and earlier posts) you were supporting the view that when lower NGDP growth was correlated to lower output and to increased unemployment that the lower NGDP growth was not a “cause” of that increased unemployment?

Scott Sumner

Aug 15 2023 at 11:38pm

No, just the opposite.

Market Fiscalist

Aug 16 2023 at 9:52am

Apologies, totally misread these posts!

I see now you were indeed talking about the relationship between unemployment and inflation and not between unemployment and NGDP growth.

Rajat

Aug 16 2023 at 8:07am

Blanchard’s thread I think confirms my (earlier MI post comment) inference that he thinks of inflation as driven by gluts and shortages/ queues. The only difference is that he seems to place emphasis on relative prices – a firm sees a glut of a commodity it sells and undercuts its competitor; the iterative price falls end when the gluts disappear. But this seems to conflate real and nominal prices – prices need to fall in real terms to address gluts. If he just assumes that real price changes imply nominal price changes, and if nominal prices fall with a given nominal money stock, the real money stock rises and real spending increases again in the old Keynesian model. Then firms presumably get back to raising real and nominal prices. I’m lost!

Scott Sumner

Aug 16 2023 at 8:30pm

Rajat, The glut/shortage approach seems to mix up cause and effect. Inflation is caused by monetary policy, which moves the equilibrium price level. Slowing inflation causes the equilibrium price level to fall. If the equilibrium price levels falls faster than actual prices due to sticky wages and prices, then unemployment rises—a glut of labor. Thus rising unemployment is often an effect of the sort of monetary policy that slows inflation. But it’s monetary policy itself that causes inflation to slow, and unemployment rises because wages and prices are sticky during the disinflation episode. If they were not sticky the tight money policy would still reduce inflation, albeit without a rise in unemployment. So unemployment is not causing the reduction in inflation.

Philippe Bélanger

Aug 17 2023 at 12:09am

I didn’t read the Bloomberg article as a confirmation of Yglesias’ tweet. He seems to be saying that everybody is forming their expectations by watching what the central bank does. But the article suggests that business owners were surprised by the price hikes. What seems to have happened is that the Peso depreciated, and the price increases quickly propagated through supply chains. I suspect that something like this also happens in the US; monetary policy announcements immediately affect things like commodity prices and interest rates, and price hikes then gradually spread through the economy. I think this way thinking is more realistic than the idea that everyone is reading FOMC press releases and making appropriate adjustments to their spending and pricing decisions. In reality, monetary policy announcements only have a direct effect on prices in financial and commodity markets, not on prices in retail stores.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Aug 18 2023 at 6:55pm

Belief in the Phillips Curve dies hard.

Comments are closed.