Scientific arguments are to be respected, and in the nearer term, anyway, we ought to heed the warnings and advice of scientists and doctors.

But when authorities proclaim the present state of emergency to be a “new normal,” we have a duty to do more than listen. We need to start a conversation. What do we mean by “normal”? Perhaps more accurately, when we finally get back to “normal,” what should it look like? (For contrasting views of what the new normal should look like see recent reports from the National Review and the Sloan Review. )

Contrary to what many might think, certain aspects of the “old normal,” so it seems to me, will have to be preserved, and this is in fact one of the lessons to be learned from our current situation.

Among the most startling aspects of the present near-cessation of most normal human interactions has been the rapidity with which wealth has simply disappeared. And I don’t mean so much the production of physical items. We actually have lots of left-over stores of material from our previously normal economic activities. We even have productive capacity in the form of still-existing firms and factories. What I mean is even more fundamental.

Wealth and How it Goes Away

The collapse of all the ordinary processes of normal exchange and investment highlight something that ought to be far more obvious to all of us.

Human wealth stems from serving subjective human wants, and those wants are ultimately served, not so much by the production of things in and of themselves, but by understanding and interpreting what is contained in the minds of others. Gaining that knowledge is what each of us does when we interact and exchange throughout all the many levels of modern civil society, whether we trade in goods, services or ideas.

Ceasing human interaction erases the means of knowing and serving these wants. If it goes on too long, even production will be impeded. Whatever a “new normal” might mean, it had better not mean interfering with these processes.

My worry is that this most basic understanding of how value is created (See here and here), will not be one of the lessons of the latest crisis. Instead, I fear that fear itself will obscure for many just how important the previously normal economic and entrepreneurial activities were for providing the current wherewithal to address the present emergency. Scientific and medical expertise, so essential in the short term, cannot be the sole or even primary source of our considerations for determining policies over the long run.

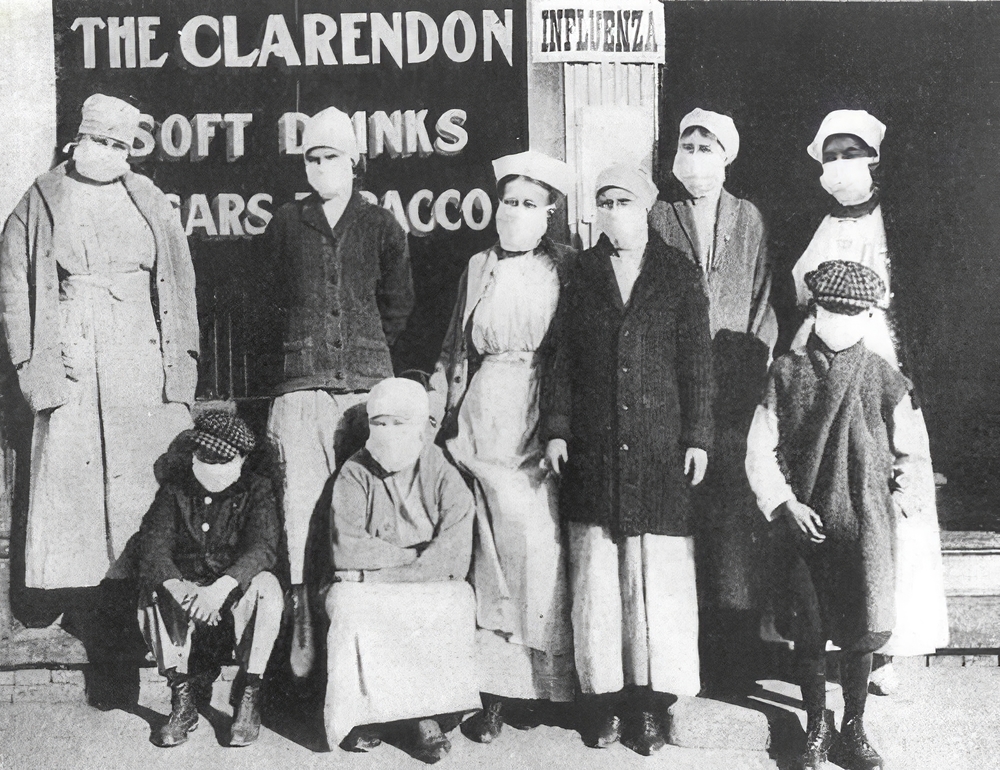

By all historical measures, we are in fact in a far better place today to deal with this situation than at any other time in our past. This was a point brought home to me by my friend and colleague, a historian of central Europe and the Near East, Dr. Peter Mentzel, who pointed to the devastating pandemic of 1918/19. I realize that many of our scientific experts have grown tired of the analogy to the seasonal flu, but there was a time when a particular strain of that bug devastated the world in much the same way that these very experts now say Covid-19 threatens us with today.

Reflecting on a Century of Growth

Only a century ago the so-called Spanish Flu took away the lives of over 600,000 Americans. Yet, for all that, Americans ultimately did not permanently shrink from their engagements with the world. Both commercial and civil life expanded rapidly throughout the 20th century, and thank goodness that it did.

It is critically important to bear in mind that the single most important reason for our improved position today, whatever we may say about specific governments and their specific policies, has been all of that previously normal free commercial and social activity that generated the wealth of the present world economy.

All of that wealth arose from the normal and daily serving of the subjective valuations of each of us. As each person navigates the complex set of interrelations that comprise our various associations, we make choices based on knowledge that only we can have of those with whom we interact. To this store of knowledge, we add our personal valuations of what is right and good. We take council from others, and learn from their examples, but our choices derive from our personal set of subjective valuations.

When we apply these valuations to the existing circumstances of our daily lives, all of the normal exchanges we engage in comprise the signals that are interpreted by our fellow human beings. Here is where that most elementary insight of Adam Smith comes into play when he pinpointed the fundamental role of specialization in the processes of wealth creation.

How such very real phenomena arise from merely subjective states of mind is to be found in the very processes of our everyday normal interactions, something we will explore in the next part.

Hans Eicholz is a historian and Liberty Fund Senior Fellow. He is the author of Harmonizing Sentiments: The Declaration of Independence and the Jeffersonian Idea of Self-Government (2001), and more recently a contributor to The Constitutionalism of American States (2008).

READER COMMENTS

Liam

Apr 4 2020 at 3:39pm

Contrasting? I don’t think those authors would materially disagree with each other’s points.

Hans Eicholz

Apr 5 2020 at 12:25pm

Yes, you are right. There need not be a substantive disagreement at the end of the day on policy, but only that they seem to set our from different suppositions. “Perspectives on” might have been a better choice of words. Thanks much!

Comments are closed.