It is not because a law has been democratically and duly adopted that it necessarily exemplifies the rule of law. It is not because democratically elected politicians govern that governing is good. One current example is given by the US and EU governments siding against Apple and in favor of its developers (outside suppliers) and competitors, under some antitrust “laws” that pretend to determine what consumers want. Another of the myriad of cases that could be cited is the US government siding with the United Steelworkers against US Steel which wants to strike a bargain with Nippon Steel. (On Apple, among other reports, see “Apple Turns to Longtime Steve Jobs Disciple to Defend Its ‘Walled Garden,’” Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2024.) Not to mention discrimination for or against preferred identity groups.

For Anthony de Jasay, the central problem with the state is that it takes sides among its citizens, favors some and harms others, which he sees as the essence of governing. His ideal and unattainable “capitalist state” would not govern: its raison d’être would be only to ensure that a worse state, intent of governing, does not take over. In other words, the problem is that the state discriminates against some citizens in order to favor others.

This idea is not quite as revolutionary as it appears. Less radical liberals believed in a similar theory. Nobel prizewinner Friedrich Hayek argued that, in the classical liberal tradition, a law must be a general and abstract rule that applies to unknown future cases and cannot target any specific individual or group. (See his Law, Legislation, and Liberty, especially Volume 1 and Volume 2.) James Buchanan, another Nobel economist, also believed that a law cannot discriminate against any individual or group (at least in a given society). The rule of law defines what we otherwise describe as a government of laws, not of men.

The rule of law in the liberal sense is more demanding than what most people (including many if not most lawyers) believe. The law is not merely a trick that allows a democratic government to do anything it wants provided it respects certain formalities, such as adoption by the two chambers of Congress and the signature by the president. For example, a “law” decreeing that all citizens will have their left arms equally amputated would be no law in the liberal sense.

To be consistent with the rule of law, a law must also have some substantive content. For Hayek, it needs to be essential for the maintenance of an autoregulated order. For Buchanan, a law must respect constitutional rules that presumptively meet the consent of all and every individual in the society. Contrary to what Vladimir Putin claimed, and despite his laughable efforts to give his state the look and feel of democracy, there cannot be a “dictatorship of the law,” for the two terms are antinomic. (On Putin’s “dictatorship of the law,” see Geoffrey Hosking, “Dictatorship of the Law,” Index of Censorship, Vol. 34, No. 4 [2005].)

The objection that the state cannot avoid discriminating is weak. Criminals are often proposed as an example. But a liberal state does not “discriminate” against criminals since laws against murder or other major threats to the ethics of reciprocity (Buchanan) or to the autoregulated social order (Hayek) are known in advance and do not identify by name any specific individual, association, or corporation. Nobody who does not want to be treated as a criminal only has not to commit such crimes. This also implies that a liberal state cannot grant a subsidy that is not available to all.

De Jasay, who was both a liberal and an anarchist, did argue that it is impossible for the state to literally treat everybody equally because equal treatment along one dimension always represents discrimination by another criterion. For example, treating everybody equally for Medicare premiums and benefits means discriminating against men, who statistically survive fewer years than women.

One objection to de Jasay’s thesis is that a state that takes sides may be welcome if, for each individual, the net effect of the multiple interventions is favorable or neutral. Many seem to think that way: “I lose this time at the roulette of politics, but I will win next time. Leviathan hates me today but he will love me tomorrow.” In reality, it is as likely that the total economic cost of state interventions is higher than their total economic benefits for some individuals. The purpose of the social contract posited by Buchanan, with its overarching rules strictly limiting redistributive policies, is to ensure that no group of individuals would be continuously exploited. De Jasay replied that such a social contract is impossible. At any rate, he would argue, churning (alternatively giving to and taking from the same individual) to the point where most people cannot know whether they are net beneficiaries of the state or not, wastes resources and reduces nearly everybody’s liberties. He envisioned the Plantation State as the end result. (See his book The State.)

The basic question is whether governing (“taking sides”) and the rule of law are compatible.

———————–

PS: My defense of Apple has nothing to do with my personal preferences. My computer fleet counts many Windows machines and only for my smartphone do I currently choose Apple. As a consumer, I would be personally more inconvenienced if Leviathan destroyed Microsoft than if it succeeds in destroying Apple. Yet Apple does provide useful competition—market competition, not competition as politicians and bureaucrats imagine in their legal dreams. I could survive with Linux.

******************************

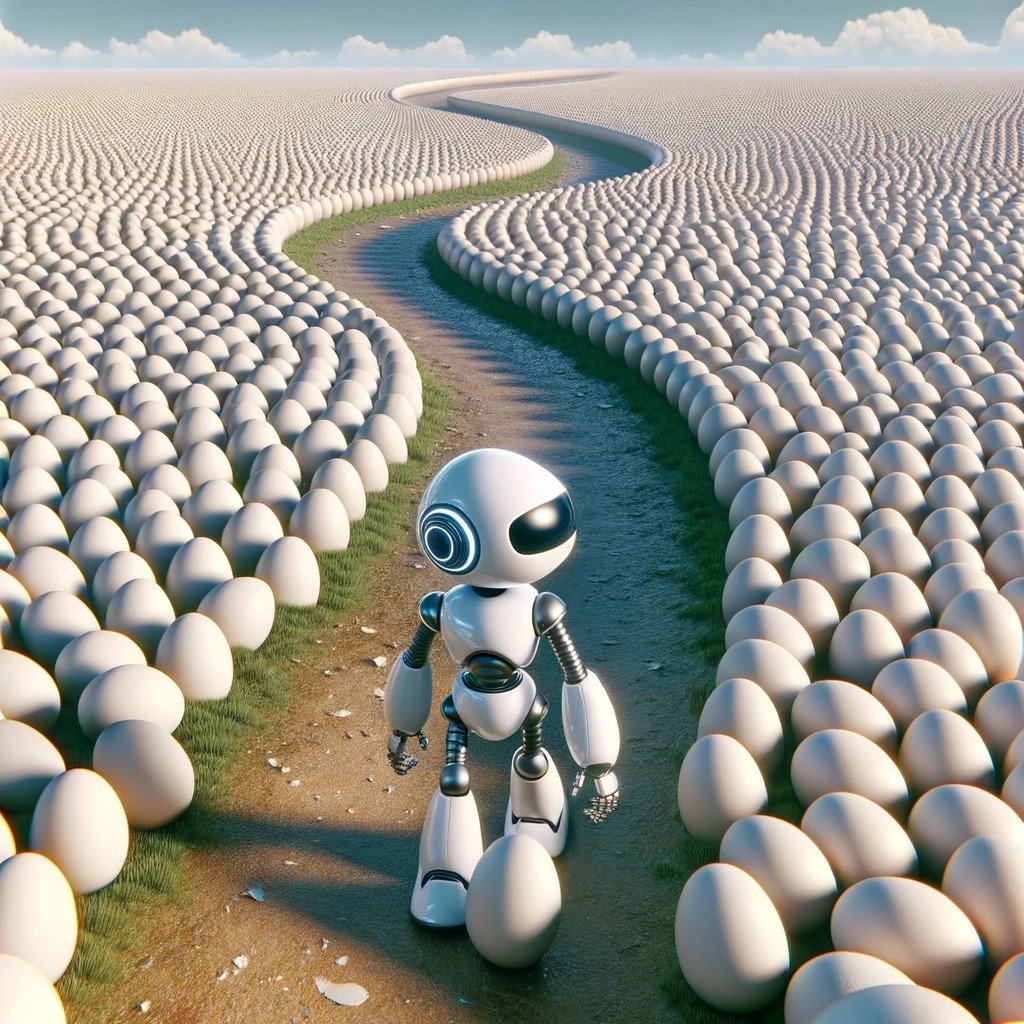

To illustrate this post, I tried to have ChatGPT and his silicon colleague DALL-E draw a large crowd of individuals without their left arms after a democratic law had forced all citizens to be equally amputated according to the so-called “rule of law.” He refused to do that. After many unsuccessful efforts, I finally gave up and asked “him”: “Generate an image showing DALL-E walking on eggshells after being asked a question that could be seen as politically incorrect. … Eggs must be everywhere in the sensitivity field with only a tiny path of political correctness.” The featured image of this post is the best one I could get, and the bot confirmed: “I’ve created a new image showing DALL-E navigating a tiny path of political correctness through a vast field of eggshells.”

DALL-E walking on eggshells in a sensitivity field with only a narrow path of political correctness

READER COMMENTS

Jon Murphy

Mar 28 2024 at 10:48am

Good stuff Pierre.

If I may offer a summary here, I read this as saying: for the rule of law to exist, both the letter and the spirit of the law must be obeyed. Vald Putin, and “dictatorship of the law,” is an example of the letter of the law being obeyed but the spirit violated.

Pierre Lemieux

Mar 28 2024 at 11:15am

Thanks, Jon. I am not sure the opposition letter-spirit is the crux of the matter. The letter of the law has specific requirements (Hayek: abstract, general, etc.). And the spirit must be consistent with the purpose of the law, which is to maintain a free society (otherwise, blunt commands are sufficient). It is admittedly difficult to summarize in a few words.

Craig

Mar 28 2024 at 11:55am

Is Apple effectively a deputized ‘para-government’?

Pierre Lemieux

Mar 28 2024 at 12:45pm

Craig: That’s a good question, but it seems to me it is (still) not very difficult to answer. If Apple were a Chinese company, the answer would quite clearly be yes. If Apple had been a Hong Kong company before 1998 and even more clearly under Cowperthwaite, or a company in another free society, the answer would obviously be no. It seems to me that America is still closer to the old Hong Kong than to China. Admitting that Apple is a “para-government” company would amount to pushing in the wrong direction.

Craig

Mar 28 2024 at 1:00pm

I am seeing a soft fascism developing, an incestuous relationship between Big Brother/Government and Big Data/Business.

Peter

Mar 28 2024 at 11:56am

Just a minor digression though it doesn’t take away from your overall point but murder is poor example as well as what is murder but state authorized killing therefore it’s subjectively tailored to discriminate against certain types of killers for no reason other than special interest pandering. For example we have decided it’s ok for the president to kill someone on his personal whim but not a organized crime leader. It’s ok to kill a kid at -6 months but not -8 months. Castle law makes self defense not murder whereas a mile away across the state border it’s murder. Honor killings, infanticide, assisted suicide, suicide itself, felony murder, summary spot executions by police, etc likewise. Murder laws discriminate no differently than laws that favor orange shirts over blue ones because murder isn’t a real objective thing, killing is. Murder is simply illegal killing and what makes it illegal is highly subjective and intentionally discriminatory not to the net benefit of society, at least not intentionally so.

Craig

Mar 28 2024 at 12:07pm

Just a brief point about Castle Doctrine. At common law the general rule is that somebody had a duty to retreat ‘to the wall’ before killing in self-defense. That was changed a bit with Castle Doctrine and there being no duty to retreat in one’s own home. I can’t think of a US state where that is NOT currently the law, the distinction tends to be between the Stand Your Ground jurisdictions and those where that is NOT currently the law, SYG imposing no duty to retreat.

In a society where firearms exist, where women are confronted by generally stronger and faster men to see an application of self defense where the state convicts because the person asserting self defense could have retreated is very uncommon and when it does become the triable issue of a case the adrenaline tunnel vision expert will typically prevail because the person asserting self defense might not even perceive the safe retreat.

Usually the problem in these self defense situations arises when the assailant himself retreats and gets the ‘shot in the back’ as the assailant is retreating, but that’s an issue even in SYG jurisdictions.

Peter

Mar 28 2024 at 12:33pm

And yet graveyards and prisons are full of people taking advantage of Castle, or to scared to do so, when a bunch of armed intruders effectively unannounced split second invade their homes in the middle of the night. You are running afoul of black letter vs law in practice.

I personally know a couple criminal home intruders and what they learned is to simply bring a friend along, kick the door down overtly, and yell police loudly and boisterously because the victim will always immediately back down until it’s to late because Castle law in practice exempts the police.

Castle Law, SYG, etc are a joke when it exempts police as you are putting your freedom in peril by invoking them.

David Seltzer

Mar 28 2024 at 5:40pm

Pierre wrote: “De Jasay, who was both a liberal and an anarchist, did argue that it is impossible for the state to literally treat everybody equally because equal treatment along one dimension always represents discrimination by another criterion.” A more recent example of the state picking winners and losers is Joe Biden’s comments to striking auto union workers. To wit.

“Wall Street didn’t build the country,” the Democratic president later added. “The middle class built the country, and unions built the middle class. “That’s a fact. Let’s keep it going.”

When I worked at 2 Wall Steet in the 1980’s, I don’t recall President Reagan showing up at 11 Wall to cheer the traders on. Just sayin!

I suspect rebuttals to The Presidents statements would take several pages of EconLog comments.

Jim Glass

Mar 28 2024 at 7:30pm

De Jasay … would argue, churning (alternatively giving to and taking from the same individual) to the point where most people cannot know whether they are net beneficiaries of the state or not, wastes resources and reduces nearly everybody’s liberties.

I give you the good people of Haiti…

… still pondering in retrospect if they were net beneficiaries of their poorish former state or not, at least now freed from the waste of resources and reduction of liberty their low-quality former state doubtless imposed on them.

Mactoul

Mar 28 2024 at 10:01pm

Jasay appears to argue against the progressive state whose main business is redistribution,

I haven’t seen any argument against the traditional notion of state whose business is security of life and liberty of the citizens.

Pierre Lemieux

Mar 28 2024 at 11:40pm

Mactoul: Wait until my Econlib review of de Jasay’s Against Politics, and you will find something close to the argument you have not seen. Of course, reading the original is better.

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2024 at 10:41am

There certainly are anarcho-liberals out there. If you want some good reading, I’d be happy to point you in that direction.

One thing I will say: often anti-liberal and illiberal folks confuse liberal arguments. Except for the aforementioned anarcho-liberals, liberals do see the state as an organization for the security of life and liberty of citizens. However, often illiberal and anti-liberal arguments for the state veer away from that traditional role. As you rightly note below, governments will violate its duty and veer into “family, marriage, inheritance, adoption etc.,” legislation which violates the life and liberty of citizens. When liberals oppose such infringements, anti-liberals and illiberals often erronously interpret those objections as to oppose the traditional role of the state.

Mactoul

Mar 29 2024 at 9:27pm

You think a society can live without any personal laws– governing family law?

Jose Pablo

Mar 30 2024 at 4:24pm

Even more! A society can live even without a government organizing “the security of life and liberty of citizens.”

See, for instance, Huemer’s The Problem of Political Authority. In particular the second part.

And this whole “organizing the security of life and liberty of citizens” is a convenient myth.

Even under a very functional government (like the American one) 241 b (2022 and growing) are spent each year in private security. More than double what different American levels of government spend in public law enforcement (129 b per year).

And despite both private and public spending on security, 11 million crimes are committed every year in the US (and only around 10% cleared by your “garantor of security”).

And the Mexican government is algo a government by any means. Look how that one protects the “security of life of its citizens”. Also the Russian government is “a government”, look how it protects the “liberty” of its citizens!

What do you think is so special about “liberal governments”? They are first and foremost, “governments” and “liberals” just as an afterthought (think of Trump’s idea of what is a “liberal government”. Much more “government” than “liberal”).

Do you really believe, for instance, that the Russian constitution is less “liberal” than the American one? You are severely mistaken if you believe so. It is a matter of institutional design and cultural norms, and you are always one January 6th away from severely altering them.

The “security” you enjoy depends first and foremost on a particular set of cultural norms widely practiced in your place of resident. Second, on the money spent on private security (which is more and more wisely spent) and only third on the money the state forces you to spend, without asking, on public law enforcement services.

This being the facts, saying that “the government organizes the security of its citizens” is just a very particular and benevolent way of looking at the works of “governments” with no real base whatsoever.

And regarding “liberty”, I don’t think that what the plantation state provides for the individual deserves that name. Granted, it could be a question of semantics. But if you use the term “liberty” for what the individual has living within the constraints of the plantation state, you need to come up with another term to define “the state of an individual unconstrained by rules forced upon him without his/her individual consent“.

Mactoul

Mar 28 2024 at 9:58pm

A vital role of a state is establishment of laws in a territory– including laws pertaining to family, marriage, inheritance, adoption etc.

Does Jasay claims that these laws also discriminate in his sense between citizens?

And how are these laws going to be established in Jasayian anarchy?

Or is it to be claimed that these laws don’t matter?

Indeed, how are laws defining crime going to be established in an anarchy?

Pierre Lemieux

Mar 28 2024 at 11:47pm

Mactoul: Conventions (of the Humean or Sugden-game theory) type would be the “laws” in anarchy. They set up some constraints on destructive self-interest (like driving on the wrong side of the road, stealing, or trying to steal it by establishing the state). The common law was similar to a set of conventions. Don’t forget that de Jasay is not the typical liberal, but he is far from the least interesting.

Jose Pablo

Mar 29 2024 at 1:23am

It is not because democratically elected politicians govern that governing is good.

This is very true (although defining “good” is pretty thorny). But there are, I think, more relevant examples than the ones that you provide, Pierre.

US democratically elected politicians have sponsored the deposition of the democratically elected governments of Guatemala and Chile and the invasion of foreign sovereign countries (several).

US democratically elected politicians have killed hundreds of thousands of innocent Japanese civilians. And US democratically elected politicians (with the necessary collaboration of Russian non democratically elected politicians) have almost got all of us killed in numerous occasions (1962, 1973, 1979, 1983 to mention a few).

“Institutional insanity” is a thing even for democratic governments. Authority cannot exist without ending up being “insane” (think of Dulle’s CIA or McCarthy’s Senate Committee on Government Operations).

Not even the US has managed to avoid this inevitable fate of even “democratically elected authority.”

Laurentian

Mar 29 2024 at 1:54pm

The classical liberals believed it was correct to discriminate against Catholics so this is questionable.

And Locke and Lilburne were fine with Acts of Attainder so they were fine with with legal formalities.

And what of the doctrine of Parliamentary Supremacy which the ckassical liberals invoked to undermine royal and church rule?

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2024 at 2:21pm

That’s obviously incorrect. See, for example, Adam Smith, David Hume, really much of the Scottish Enlightenment, James Madison, etc.

Laurentian

Mar 29 2024 at 5:39pm

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2024 at 7:12pm

The Irish Penal Laws were stauchly denounced by classical liberals in the UK (Burke himself called them “a machine of wise and elaborate contrivance, as well fitted for the oppression, impoverishment and degradation of a people, and the debasement in them of human nature itself, as ever proceeded from the perverted ingenuity of man”). Indeed, the liberal government in Britain put much pressure on Ireland to repeal them, which they eventually did. So, that’s evidence against your claim, not for it.

The German liberals orignally supported kulturkampf, but eventually denounced that given how anti-Cathloic it became. So, again, evidence against your claim.

Have you better evidence?

Laurentian

Mar 29 2024 at 8:44pm

Burke was born decades after the Glorious Revolution. The classical liberals who engaged in the Glorious Revolution passed more Penal laws. The classical liberals only turned against the Irish Penal laws decades afterwards.

And 19th Century classical liberals still disliked Catholics. Here is Herbert Spencer:

https://praxeology.net/HS-FC-25.htm

There is a return towards that subjection to a priesthood characteristic of barbaric types of Society. Rebellion of the Church against the civil power, is an indication of desire for that social régime which once made kings subject to the Pope. Throughout the hierarchy the strengthening of sacerdotalism is the aim, secret if not avowed; and the heads of the hierarchy when asked to put a check on those practices which assimilate the Church if England to the Church of Rome, evade and shuffle in such ways as to let them go on, while they are energetic in resisting efforts to prevent the assimilation. For a generation past there have been endeavours to mark off the priesthood as a body of intermediaries between God and man. Confession, the performance of a quasi-mass, and various ceremonies with incense accompaniment, have tended more and more to elevate the clerical class: the effects being re-inforced by gorgeous robes and jeweled symbols, such as were common in mediæval days and are akin to those of barbaric peoples at large.

I find this questionable. The German liberals of the time were avowedly anti-Catholic. They made this clear in their public statements. It was a German Progressive (e.g. an anti-Bismarck liberal) Rudolf Virchow who coined the term kulturkampf which he meant as a positive. If anything the German Liberals thought the kulturkampf wasn’t going far enough. The German conservatives were the ones who turned against it. And the kulturkampf ended primarily because Bismarck didn’t like the Catholic and Conservative resistance and needed support for his protectionist policies.

Pierre Lemieux

Mar 29 2024 at 6:53pm

Laurentian: Please stay in the 19th century or with its liberal predecessors or its descendants. One short thing to read is Tyler Cowen’s “A Profession With an Egalitarian Core,” New York Times, March 16, 2023. David Henderson quoted two paragraphs on EconLog. I give related quotes in an EconLog post on canceling Marx.

BS

Apr 5 2024 at 12:23pm

Rule of law: the rules are published in advance where everyone can see them; the meaning of the rules doesn’t change if the meaning of any of the words or phrases in them evolves; the rules are applied consistently without fail.

Comments are closed.