Twenty years ago, my wife and I faced the question of how to save for my daughter’s college education. (BTW, why did I have to pay for both my college education and my daughter’s?)

Suppose I had suggested the following plan to my wife:

We’ll invest $10,000/year in collectables. We can buy some Song dynasty porcelain, ancient Greek coins, 17th century French furniture and etchings by Durer, Goya and Rembrandt. Then we’ll sell them after 18 years to pay for her college.

I’m guessing that my wife would accuse me of mixing up two very different issues, how much to save and how much to indulge my passion for antiques. You can save money by investing in antiques, but the return is likely to be disappointing given the extreme illiquidity in the market for collectables. Instead, we chose a mutual fund.

Ten years ago, John Cochrane wrote a widely misunderstood essay on fiscal policy. Paul Krugman criticized the paper, but probably did not read it to the end:

In sum, there is a plausible diagnosis and a logically consistent argument under which fiscal stimulus could help: We are experiencing a strong portfolio, precautionary, and technical demand for government debt, along with a credit crunch. People want to hold less private debt and they want to save, and they want to hold Treasuries, money, or government-guaranteed debt. However, this demand can be satisfied in far greater quantity, much more quickly, much more reversibly, and without the danger of a fiscal collapse and inflation down the road, if the Fed and Treasury were simply to expand their operations of issuing treasury debt and money in exchange for high-quality private debt and especially new securitized debt. . . .

My analysis is macroeconomic, and does not imply anything about the specific virtues or faults of the Obama team’s spending programs. If it’s a good idea to build roads, then build roads. (But keep in mind the many roads to nowhere, and ask why fixing Chicago’s potholes must come from Arizona’s taxes funneled through Washington DC.) If it’s a good idea for the government to subsidize green technology investment, then do it. (But keep in mind that the internet did not spring from industrial policy to improve the Post Office, the word processor did not come from a public-private consortium to rescue the typewriter industry, and that a huge carbon tax is much more likely to spur useful green ideas, and the only way to spur conservation.) The government should borrow to finance worthy projects, whose rate of return is greater than projects the private sector would undertake with the same money, spreading the taxes that pay for them over many years, after making sure its existing spending meets the same cost-benefit tradeoff. Just don’t call it “stimulus,” don’t claim it will solve our current credit problems, “create jobs” on net, or do anything to help the economy in the short run, and don’t insist that we have to pass this monstrous bill in a day without thinking about it.

If you like antiques, it might make sense to buy some antiques. But don’t pretend that you are saving for your daughter’s college education, and don’t time your purchases of antiques to coincide with the need to save money for college.

If the government needs to issue debt to stimulate the economy (I doubt that it does), then use it to buy some highly liquid assets, and sell them off when the economy no longer needs such a large supply of Treasury debt. But don’t mix up the completely unrelated issues of the appropriate level of government spending with the need for more public debt. Boosting government spending as a way to stimulate the economy makes no more sense than buying antique French furniture as a way of saving for college.

PS. My favorite line from Cochrane’s 2009 article:

Some economists tell me, “Yes, all our models, data, and analysis and experience for the last 40 years say fiscal stimulus doesn’t work, but don’t you really believe it anyway?” This is an astonishing attitude. How can a scientist “believe” something different than what he or she spends a career writing and teaching? At a minimum policy-makers shouldn’t put much weight on such “beliefs,” since they explicitly don’t represent expert scientific inquiry.

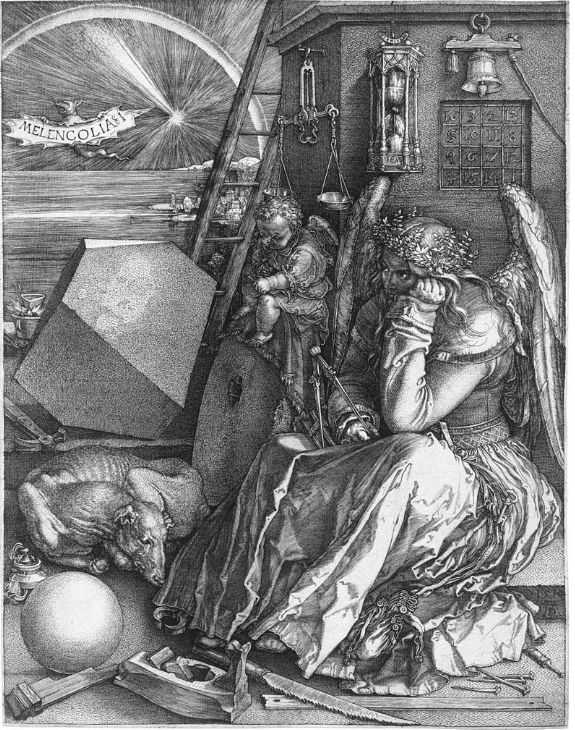

PS. Durer portrays Cochrane contemplating the state of modern macro.

READER COMMENTS

Thaomas

May 8 2019 at 2:24pm

If in a recession, government simply increases spending on things with present costs and future benefits that pass NPV test, that would look a lot like a “stimulus” and would be calibrated to the state of the economy not to ex-ante guess about the size or duration of the need for “stimulus.” It would prevent the mistake of reducing spending because of “debt” or the “deficit” both of which should enter spending decision as they affect the borrowing rate implicit in the NPV discount rate.

Michael Rulle

May 13 2019 at 11:17am

I do question the premise that Government spending produces a measurable NROI. My skepticism is based on my perception that the Government in fact never produces such data. The Fed did publish that it earned profits on its QE programs—-so maybe that is an exception (not saying if that was a positive a negative or a zero-sum neutral—-the latter is my guess). Buy as it relates to fiscal policy, I have never seen this—-would love to find out I am wrong.

Scott Sumner

May 8 2019 at 2:36pm

Thaomas, You are just repeating Cochrane’s point.

Phil H

May 8 2019 at 5:00pm

I can’t see the point being made here… no, sorry, that’s unnecessary rhetoric. I can see the point, but it’s wrong.

If Cochrane is arguing that we should call a spade a spade then…

The government employing people is creating jobs.

The government spending money is expanding the economy.

Those two are true by definition.

Now, Cochrane believes an economic theory which says that when the government spends money and creates jobs in a particular way, it is necessarily (at least) balanced out by losses in other parts of the economy. So his theory leads him to look beyond the surface facts to a deeper level of economic reality, and he sees bad things. Krugman believes a different economic theory, and he sees something different.

But there is no “just the fact, ma’am” way of looking at things that supports C’s theory over K’s. “Just” looking at roadbuilding as an investment isn’t a simple, ideology-free perspective. It’s a claim that the government ought to act like a market participant in ways that it hasn’t previously. I guess it’s a reasonable argument to make, but I find Cochrane’s rhetorical positioning a bit disingenuous.

Paul R

May 9 2019 at 10:00am

Side note: are the blue-colored names intended to be links to the referenced articles?

The Cochrane essay: https://delong.typepad.com/sdj/john-cochrane-february-27-2009-fiscal-stimulus-fiscal-inflation-or-fiscal-fallacies.html

I was unable to find Krugman’s criticism.

Paul R

May 9 2019 at 10:02am

Here is Krugman’s criticism of Cochrane: https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/01/27/a-dark-age-of-macroeconomics-wonkish/

Travis Allison

May 9 2019 at 10:55am

>(BTW, why did I have to pay for both my college education and my daughter’s?)

Baumol’s cost disease. Lazy college professors haven’t increased their productivity in 100 years. 😉

Craig

May 9 2019 at 11:48am

“(BTW, why did I have to pay for both my college education and my daughter’s?)”

Because you want better for your children.

It’s what dads do!

Scott Sumner

May 9 2019 at 1:21pm

Phil, You said:

“The government employing people is creating jobs.

The government spending money is expanding the economy.

Those two are true by definition.”

I think you might want to look up the definition of definition.

Thanks Paul, I added the links.

Craig, My dad didn’t want “better”?

Phil H

May 10 2019 at 4:59am

I’m genuinely unsure what you mean. I was suggesting that on one (shallow) level, it is merely a truism that giving a person a job expands employment. Is that wrong?

Comments are closed.