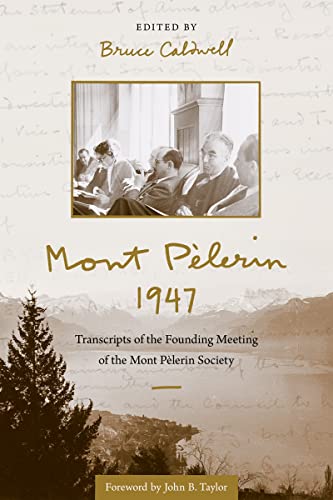

Part of how I used the time during our extensive power outage was to read, by lantern, most of Bruce Caldwell, ed., Mont Pelerin 1947. Published by Hoover Institution Press in 2022, it’s a recounting, with transcripts of the various discussions, of the first meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society at, you guessed it, Mont Pelerin in Switzerland.

The highlight for me was the discussion of Germany. Remember that it was 1947 and Ludwig Erhard hadn’t yet abolished price controls. The price controls were still enforced by the Allies, and were leading to widespread barter and close-to-starvation diets. I tell the story at some length in “German Economic Miracle,” in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

I found two things interesting: (1) German economist Walter Eucken’s clear thinking about the devastating effects of price controls and (2) the fact that even some of the prominent free-market economists at the meeting weren’t convinced that price controls should have been removed immediately.

On point (1):

Eucken: It was very surprising that occupation did not mean the end of the Nazi system. Their price and distribution system was preserved in all detail and with only little change in personnel. (p. 117)

Eucken: The rations are so small that nobody, literally nobody, can live on them. (p. 117)

Eucken: To compress all this in a slogan, the German economy is undergoing a progressive primitivisation and now corresponds to the economic system of the 6th and 8th centuries. (p. 118)

Eucken (after advocating currency reform): Further, if rationing and the price stop are maintained, the only effect will be that there will be no supplies. The official low prices reduce what is available in the market.

I believe prices must be allowed to rise but only if at the same time a free market and international trade are resumed. (p. 121)

I confess that I don’t understand two things about his last statement. First, what does he mean by “free market?” I would have thought that in this context it means no price controls, which is covered by “prices must be allowed to rise.” But maybe he’s saying that allowing them to rise is not enough—that they must rise to free-market levels. I don’t know. Second, while of course, international trade should have been resumed and, if resumed, would improve things, why hold up deregulation of prices if international trade is not resumed?

On point (2) about economists not being convinced that price controls and/or rationing should be removed immediately:

Lionel Robbins: I know of no properly instructed person at home who would argue at this point that the policy of a price stop was a wise policy. But I do not think the consumption rationing system can be removed. But price stop can only be removed on grounds of politics. (p. 124)

Karl Brandt (in response to Robbins): I did not intend to comment on the British situation. I would still cling to my notion that the possibility of establishing in Germany a free price market system, particularly with respect to food, without first having replenished the stocks, would absolutely lead to starvation, unless you took a large number of people and fed them on public relief. (p. 124)

Caldwell explains in a footnote on p. 124 that “price stop” means “price ceiling.”

Robbins was, of course, a prominent economics professor at the London School of Economics. Here’s his bio in David R. Henderson, ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Karl Brandt was a German economist who had fled from Germany to the United States in 1933, shortly after Hitler’s election.

It’s astounding to me that Brandt didn’t understand that the amount of a good supplied (he calls them “stocks”) will rise if the price is allowed to rise from a price ceiling situation.

Eucken, by the way, gives an answer to Brandt that is similar to mine:

Eucken: The situation would be different if we had a fixed amount of goods to distribute, but the central problem is the effect on current production. (p. 125)

Milton Friedman adds:

I think it is a fallacy that a free market is something that rich nations can afford, but that poor nations must do without. I think the U.S. never had any reason to have any rationing or price control at all. (p. 125)

Karl Brandt does have one great insight, and his having fled from Germany in 1933 gives him credibility. He states:

After destruction of physical assets, the Allies’ policy bought about the destruction of personal capital. That is, if anyone had invested under the Nazis, it was taken for granted that the person was persona gratissima with the Nazis. Rate at which the tribunals work is very slow. Germans talk of “Hitler’s 1000 years’ Reich, 14 years of Nazism, 986 years of denazification. By this slow rate, you are not getting rid of Nazis. And they are not permitted to work. Their children suffer. And the system will have a very bad effect on the children, who will have as a result a hatred of the Allies and of their methods.

Fortunately, things turned around dramatically the next year with Erhard’s reforms and so there did not seem to be much resentment of the Allies. (Notice the fact that not all the notes are in sentence form. I’m pretty sure this is because the person taking notes was Dorothy Salter Hahn, the wife of economist Frank Hahn, and people were often talking at lightning speed. Frank Hahn, by the way, did not attend.)

Here’s an interesting segment of the Wikipedia entry on Eucken:

During the Nazi period, Martin Heidegger became rector (head of Freiburg University) and imposed the regime’s policies. Eucken was vocal in opposing these in the university’s Senat. Some of his lectures in the 1930s resulted in protests from the local Nazi student association.[3]

After the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, Eucken was one of several Freiburg academics who banded together with several local priests in a so-called Konzil, where they debated the obligation of Christians to fight against tyranny. The Freiburg Circles had links to Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, key figures of the resistance against Hitler. Bonhoeffer asked Eucken, Adolf Lampe and Constantin von Dietze to write an appendix to a secret memorandum, in which they worked out a post-war economic and social order. The central planning system of the Nazis was to be replaced with a liberal competitive system. If the attack of 20 July 1944 had succeeded, these plans would have been the basis of a new economic order. After the coup failed, Lampe and von Dietze were arrested and tortured by the Gestapo. Eucken, too, was arrested and interrogated twice but released. Two of his friends were executed.[3]

Caldwell says that Hayek called Eucken “the star of the [Mont Pelerin] conference.” (p. 28)

In David R. Henderson and Steven Globerman, The Essential UCLA School of Economics, we tell of Jack Hirshleifer’s work on disaster and recovery in postwar Germany. The starvation issue was serious indeed.

One final note: On page 35, Caldwell lists the 39 attendees, not counting Dorothy Hahn. I knew 6 of them.

HT2 Eric Wakin at Hoover.

READER COMMENTS

Fazal Majid

Mar 20 2023 at 9:17am

It’s impossible to discuss this in a vacuum. The Morgenthau Plan to starve the Germans back into the Middle Ages was very much still in effect until 1947. In this light, the Allied (mostly US) policies take on a much more sinister turn. Eucken was arguing for the survival of ~25M people, as estimated by Herbert Hoover.

Todd Ramsey

Mar 20 2023 at 9:59am

Perhaps telling that Brandt denoted food supplies as “stocks” rather than “flows”?

Jon Murphy

Mar 20 2023 at 10:42am

I encountered similar comments from some economists at the beginning of the COVID pandemic when Fauci et al were calling for price controls on PPE and in support of price-gouging legislation. Supply curves are supposedly perfectly inelastic in the short-term following a shock like a hurricane or pandemic, so a price ceiling won’t lead to shortages and just prevent prices from rising.

Of course, as Eucken, Friedman, and others point out, the assumption of perfectly inelastic supply is false. But even if it did hold, price controls would still lead to the DWL that arise from shortages: queuing, alternative forms of rationing, etc.

Knut P. Heen

Mar 20 2023 at 1:03pm

We have to remember that grain and potato are both capital goods (seed) and consumer goods. This may be the reason Brandt refers to the stocks. The amount produced is limited by the seed stock. It is not obvious how higher prices affect the seed stock. My intuition tells me that the answer is that you increase the seed stock and reduce current supply in order to increase future supply, but I would have to do the math to be sure. The opposite seems to deplete the seed stock completely. Sherwin Rosen wrote a paper about potato paradoxes. I seem to recall that this is one of the paradoxes. Higher prices leads to less supply in the short-run.

Comments are closed.