One of the unfortunate failures caused by society’s focus on natural sciences is that we often overlook crucial social scientific applications. One such failure is the idea that there is an important difference between “renewable” and “non-renewable” resources. There isn’t. In fact, some non-renewable resources—such as oil—are not even meaningfully finite.

This insight, original to the late economist Julian Simon, is based on a proper understanding of economics. To explain why the concept of renewable resources is vacuous, we’ll start by talking about the relationship between physical quantity and human wants.

What Do You Want?

When you go to the gas pump to fill up your car, what is your goal? I think the straightforward answer is that you want to go somewhere relatively fast. Likewise, when you turn on a gas stove, what do you want? Well, likely you aren’t turning it on for the smell— you want to eat something.

People don’t ultimately care about physical quantities of resources. A person doesn’t go to the pump to get X gallons of gas. People fill their tanks so they can drive.

Humans demand the services that resources provide, not the physical amount of resources themselves. Another way of putting it is resource use is teleological in nature. That just means that resource use relates to human purposes.

How many gallons of gasoline there are doesn’t matter to people. Instead, they care about getting to their destination.

Renewing the Non-renewables

This is the first key to understanding why your science textbook wasn’t teaching you much in the chapter about “renewable” resources. Since we care about resources for the services they provide, we don’t need to “renew” resources to make them more plentiful. Instead, all you have to do is increase the services yielded by a given quantity of resources. Consider this example:

Imagine you live in a small country with only 500 gallons of oil available. Your cars get 10 MPG and the small population drives 100 miles/day in total. How many days will the supply last? Well, if you drive 100 miles getting 10 MPG, that means you use 10 gallons a day. At this rate, the 500 gallons are used in 50 days. Engineers calculate this and panic sets in. “We’ve reached peak oil” headlines top newspapers.

However, let’s say a clever entrepreneur invents a more efficient engine—efficiency jumps up to 20 MPG. Now your country only uses 5 gallons per day, and there are 100 days of gas. By improving technology, the amount of services gasoline provides has increased. As far as human wants are concerned, our non-renewable resource has doubled in size.

Can this process continue? Of course! So long as the efficiency of energy use improves at a faster rate than the stock falls, the resource will continue to grow in size. In fact, it’s possible technological progress could make increasing the services of gasoline cheaper than harvesting a renewable alternative.

Our growing supply of “non-renewable” resources

Technology can improve in several ways: plant oil can be mixed with fossil fuel to make it last longer, new techniques for harvesting previously unharvestable oil can be used, and efficient improvements in commutes can all increase the amount of oil.

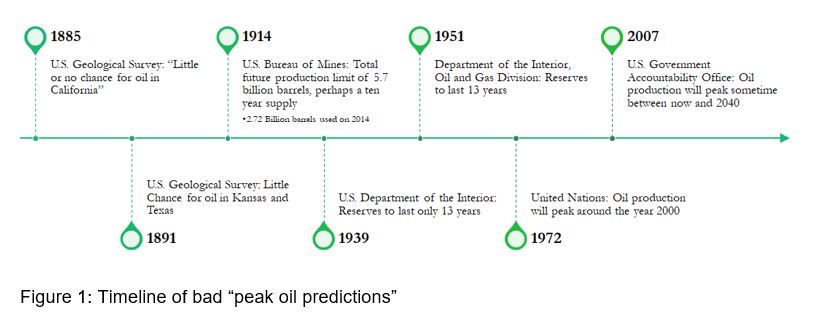

Skeptics may still respond, “maybe something like this can work on paper, but surely this isn’t how things work in the real world.” But skeptics are wrong. Over the last century, several doomsayers have announced the end of peak oil. Each step along the way, they have been wrong.

Further evidence comes out of Drs. Tupy and Pooley’s work at HumanProgress with the Simon Abundance Index. The Simon Abundance Index measures the amount of time it takes to acquire resources by considering the price of the goods compared to hourly income. If a good were becoming more scarce, it would be increasing in this “time price.” However, crude oil has become more abundant. The same amount of time working today can purchase 2.84x more oil than in 1980.

The Ultimate Resource

So, if you have been feeling pessimistic, renew your hope! People’s capacity to think of innovative, creative solutions to problems is the well that never runs dry. Our world is more complex than being pigeonholed into working with only one of two categories of resources. So forget the broken renewable/non-renewable dichotomy. As Julian Simon pointed out, people are the Ultimate Resource, and all other resources are created from the same place: the human mind.

Peter Jacobsen is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Ottawa University and the Gwartney Professor of Economic Education and Research at the Gwartney Institute. His research is at the intersection of political economy, development economics, and population economics.

READER COMMENTS

David Seltzer

Jan 26 2023 at 6:04pm

“new techniques for harvesting previously unharvestable oil can be used,”

I Remember Paul Ehrlich’s warning; “Do we really want to threaten to blow up the world over a resource which we know damn well is going to be gone in 20 or 30 years anyway?” Horizontal Directional Drilling was developed in the 1970s. Today, oil and natural gas reserves found in separate layers underground are accessed via multilateral drilling. Multilateral drilling lets producers branch out from the main well to tap reserves at different depths, increasing production from a single well while reducing the number of wells drilled on the surface. Seems like there is an environmental benefit as well.

Warren Platts

Jan 29 2023 at 3:32pm

70s were a little early, I think, by about 30 years! The key to directional drilling technology was actually the adoption of Russian “mud motor” drilling bits. U.S. drilling in those days was all rotational: the entire drill string would rotate. Ironically, Russians (or Soviets I should say) couldn’t use rotational drilling because their steel was too poor; the pipes would twist off and break. The mud motor, however, depends on the drilling mud pumping through the system for its power. Thus if you align it, just right, you can get it to drill in a preferred direction.

Henri Hein

Jan 26 2023 at 7:18pm

Your point about increasing the efficiency of existing fuel technologies is a good and underappreciated one.

I share the concerns some environmentalists have about fossil fuels, but I have always thought the “renewable” term is problematic. Take a windmill. Over the course of its life, it will need maintenance and parts replacements. Eventually it will break down and will have to be taken out of service. It’s not ‘renewable’ in the automatic sense the term implies. To properly compare windmills to fossil fuels, you have to calculate for each what total resources and side-effects are involved to produce a unit of energy.

Knut P. Heen

Jan 27 2023 at 9:45am

I took a course in resource geology the same semester I had my first microeconomics course when I did my engineering degree in applied geophysics. The definitions used in the resource geology course were economic ones. What can be produced at current prices had one definition. What can be produced at higher prices had another definition. The professor who taught the course also made fun of “peak oil”. This was 30 years ago. The distinction between renewable and non-renewable must come from somewhere else. I think it comes from a science without equilibrium models. Many resources, for example a water well, will refill at a certain rate and will run dry if you tap it faster than it refills. Is the water well renewable or not? The same is true for a hydroelectric plant. Once the water reservoir is empty, there is no electricity until it refills.

Oscar Cunningham

Jan 27 2023 at 10:39am

From the title I thought your point was going to be in the other direction. Because of discounting rates, renewable resources have a finite present value.

Comments are closed.