During the 2000s, China was accused of currency manipulation. Many observers claimed that this policy hurt America’s tradable goods sector, boosting our current account deficit. Some argue that this led to a net loss of jobs, and/or de-industrialization. Here I’d like to point out that the same models that suggest China’s currency manipulation hurt our tradable goods sector also imply that America’s recent fiscal policy hurts this sector even more, indeed by much, much more.

The current account is domestic saving minus domestic investment. If foreign countries boost their foreign exchange reserves by purchasing assets in the foreign exchange market, then this will generally tend to boost their saving rate, and thus their current account balance. Because global current account balances must total zero, this will tend to reduce foreign current account balances. Pundits call this “currency manipulation”, but it’s actually saving manipulation. It can just as easily be done by countries that lack their own currency, such as Germany.

The most famous example of this process is China, where the current account surplus peaked at 10% of GDP in 2007 ($353 billion). Fred Bergsten and Joe Gagnon (2017) produced one of the best studies on currency manipulation, and they suggest that China’s purchase of foreign assets was much larger than necessary, and that without these excessive purchases their current account would have been near zero in 2007 (i.e. roughly balanced.)

In my view, only a portion of China’s 2007 CA surplus was caused by currency manipulation, but I’ll provisionally accept the Bergsten/Gagnon estimate, as they have more expertise in this area than I do. Thus I’m taking the estimate that is most favorable to the point of view I’m about to criticize.

If China actually was guilty of this much currency manipulation, then the rest of the world saw its current account balance “worsen” by $353 billion. We really have no idea how much of that burden was imposed on the US, but given that our economy was roughly a 1/4th of the global economy, $100 billion seems like a ballpark estimate. (In fairness, there’s substantial uncertainty here, and the US share might be higher.) Our deficit in 2007 was $711 billion, so without China’s currency manipulation it might have been in the $600 to $620 billion range.

Just so you don’t think I cherry picked dates, if I’d used 2006 then China’s impact on the US would have been much smaller, certainly less than $50 billion, and the US current account deficit was $805 billion in 2006. So in 2006, China’s impact on the US current account was quite small. I choose 2007 because it was the “worst” year of China’s currency manipulation.

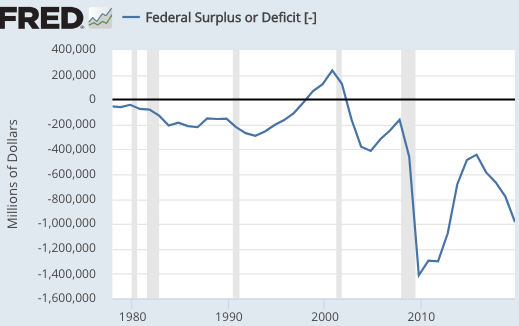

If you accept the sort of economic model used by Bergsten/Gagnon and other economists who are worried about currency manipulation, then it’s important to recognize that these models predict that domestic fiscal policy will also impact the US current account. Since 2015, we’ve had an experiment in fiscal policy that’s unique in US history; the budget deficit has soared dramatically higher despite falling unemployment and no foreign war. That did not happen in the last half of the 1990s, the last half of the 1980s, or even the last half of the 1960s (despite Vietnam), which were similar periods of economic growth and falling unemployment. Deficits usually increase during recession and decline during expansions.

The Bergsten/Gagnon study found a coefficient of 0.54 in a regression looking at the impact of changes in the cyclically adjusted budget deficit on the CA balance for open economies such as the US. This means that an extra $1 of budget deficit will add 54 cents to our current account deficit. Between 2015 and 2019, the budget deficit grew by $542.4 billion, and I’d guess the cyclically adjusted deficit grew even more (as unemployment was falling.). But let’s take $542.4 as a conservative figure. That means that recent fiscal policy has boosted our current account deficit by $292.9 billion, which is far more than the 2007 China shock, even as a share of GDP.

Yes, our current account deficit did not grow by that much, which means either that “other things were not equal” or the parameter estimate is wrong. Other factors such as the trade war and the fracking boom may have impacted the CA balance. In my view the more likely explanation is that neither budget deficits nor foreign exchange invention have quite as big an impact as B/G estimated, but that’s just a hunch. The point is that if these models are correct, then they suggest that the recent fiscal shock damaged our tradable goods sector far more than the famous “China manipulation shock”. And keep in mind that our current account deficit actually shrank in 2007 as compared to 2006, despite the huge increase in Chinese currency manipulation. So one is never going to find a perfectly clean estimate where everything else is held constant.

Just to be clear, the famous “China shock” research of Autor, Dorn and Hanson was not just about US and Chinese current account balances. Even if China had done no currency manipulation, its rapid rise as a trading power would have accelerated the re-allocation of lower skilled manufacturing to East Asia, and this would have hurt certain sectors of manufacturing in the US. Here I am considering the so-called “unfair” part of the China shock, not the normal creative destruction of shifting patterns of trade. And as for the “Trump fiscal shock”, I’m also adding in the increase in our budget deficit that was already underway before he took office. This explains why “manipulation” and “mostly” were put in parentheses in the post title.

If your intuition suggests that fiscal stimulus can’t possibly be as damaging to our labor markets as Chinese currency manipulation, then you need to re-examine your intuition. Thus some might argue that the China shock reduced US aggregate demand whereas the recent fiscal stimulus increased US aggregated demand. But even Keynesians like Paul Krugman acknowledge that back in 2007 the Fed was offsetting the impact of China on aggregate demand, and between 2015 and 2018 the Fed raised interest rates 9 times to keep aggregate demand at a level that their (flawed) Phillips Curve models suggested was appropriate at the time. When not at the zero bound, the alleged problem with currency manipulation is sectoral, not aggregate demand related.

In that case, why do people worry about foreign currency manipulation during periods when the economy is not at the zero bound, such as 2007? The main answer seems to be that while foreign CA surpluses don’t reduce overall US employment, they do reduce employment in manufacturing. Back in 2007, people complained about industrial jobs being replaced with “hamburger flippers”. But if that’s your concern, then you need to consider the fact that this sort of sectoral reallocation is equally likely to occur when our CA surplus deficit is enlarged by highly expansionary (indeed inappropriately expansionary) fiscal stimulus. If the deficit were caused by government spending on infrastructure, then the fiscal stimulus might boost manufacturing. But as Krugman recently pointed out, it’s been mostly caused by tax cuts, with almost no increase in infrastructure spending:

Could Trump have been more successful at boosting manufacturing? Well, things might look very different if he had actually followed through on his campaign promises to make big investments in infrastructure, which would have created a lot of sales for U.S. manufacturing.

If the economists who worry about currency manipulation are correct, then recent fiscal policy has damaged the US industrial sector far more than the peak period of Chinese currency manipulation. Hardly anyone seems to make this argument, which is just another reason why I suspect people are overestimating the damage done by foreign currency manipulation. It’s not that they are wrong; it’s just that the damage is probably not as severe as is widely assumed.

PS. The Bergsten/Gagnon empirical work is more sophisticated and complex than what I presented, but I don’t believe the broad outlines of my analysis would be changed by getting into all the details. Please correct me if I’ve missed something important.

READER COMMENTS

Thaomas

Nov 4 2019 at 9:17pm

I’ve never been able to make any sense of claims that trade policies affect US trade balances — domestic tariffs, foreign subsidies, or currency “manipulation” unless the latter means investing in the US.

Don Boudreaux

Nov 5 2019 at 6:34am

Scott,

Excellent post.

But I think that you mean to say “our CA deficit” (rather than “our CA surplus”) near the end when you write:

(I assume that by “CA” here you mean “current account” and not “capital account.” Forgive me if I’m missing something.)

Scott Sumner

Nov 5 2019 at 10:25am

Thanks Don, I’ll correct that.

Michael Rulle

Nov 5 2019 at 9:07am

During the mid 1980s, when Japan was about to take over the world and the imperial palace (which I used to take morning jogs by back then) was supposedly worth the same value as California, its currency increased in value by about 60% to 1 dollar to 100 yen in just a few years. Then the great Japanese equity market collapse happened. For all practical purposes it has “stabilized” around about the 80-120 range since about the early 90s. After about 5 years into China’s entry into the WTO in 2001 the yuan increased in value by 25% gradually over the next 10 years, before getting cheaper again——declining to 7 Yuan per dollar. Over the last 7 or 8 years.

I do not see any relationship to currency values between these two nations and the US. Generally, as economies get much stronger, their currencies strengthen, particularly when they arise from almost nowhere. The Yuan, however, has had a relatively narrow range. Since 2001, the Yuan has been between 6 and 7 per dollar. I would have guessed it should be stronger.

In political terms, the benefit to the US of a cheap Yuan, is spread among mostly consumers, who cannot directly observe the benefit. But the savings results in either more consumption and or more savings. But in “Business terms” it is much easier to see the industries impacted—-hence it is easier to demagogue. Currency manipulation seems to be a fools game.

Scott Sumner

Nov 5 2019 at 10:26am

Michael, China’s current account is now close to balanced.

tpeach

Nov 6 2019 at 10:56pm

Hi Scott

Does CA=S-I in a country without its own currency? (Or in a US state or city?)

The part about Germany confused me because I can’t see the mechanism for bringing the two sides into equilibrium without the exchange rate adjusting.

tpeach

Nov 6 2019 at 11:07pm

Actually, having thought about it a bit more, I may have answered it myself.

Is it the real exchange rate that matters, rather than the nominal, so even in a common currency area the adjustment can still take place?

Scott Sumner

Nov 7 2019 at 1:01pm

Yes, the German’s did some reforms in the early 2000s to reduce their real exchange rate by reducing wages. This brought their unemployment rate down from 11% to 3%

Comments are closed.