Here’s an imaginary conversation between an alien from outer space and a human:

Alien: What do you mean by the phrase: “What goes up must come down”?

Human: It’s just a law of nature, the effect of Earth’s gravity.

Alien: I’m not sure that’s always true; our sensors detected a human space probe out beyond the Kuiper Belt, which shows no signs of “coming down”. But I’m more interested in how the phrase is used elsewhere, as in this graph in a magazine called “The Economist“:

What does this graph show?

What does this graph show?

Human: It shows what is called a bubble. The price of Bitcoin rose to a peak of $19,000, after which it inevitably fell back down.

Alien: I think I know the meaning of the word “peak”, it refers to the top of a mountain, is that right?

Human: Yes.

Alien: So you are saying that if an asset price moves in a pattern that looks like a mountain peak, then it shows that what goes up must come down?

Human: Yes.

Alien: OK, but I’m still a bit confused. Is this “what goes up must come down” statement an assertion about how the world behaves, or is it a description of what mountain peaks look like?

Human: I don’t follow.

Alien: You said a very high peak in asset prices is inevitably followed by a sharp drop. But you seem to define “peak” as a point on a graph where the line slopes sharply downward, both to the left or to the right. I can’t tell whether this is simply a description of peaks, or a causal statement about the behavior of asset prices.

Human: I see your point. Let me be more specific. The phrase “what goes up must come down” refers to the fact that when an asset price soars to an unreasonably high point, it will inevitably fall back over time.

Alien: How do we know when the price has reached “unreasonable” levels? Aren’t asset prices supposed to represent some sort of market consensus as to what the asset is worth? Why would investors pay an amount that was unreasonable?

Human: Here you need to divide the public up into two groups, irrational investors and rational experts.

Alien: So you are saying that when Bitcoin prices reached $19,000, the experts saw that this price was irrational, but the investors did not?

Human: Yes.

Alien: Can you provide me with a list of some representative experts?

Human: Here you go. (Alien quickly processes list and searches the human internet.)

Alien: I see that most of your experts did indeed claim that Bitcoin prices were unreasonably high at $19,000. But they also thought that Bitcoin prices were unreasonably high at $1000. Indeed many thought that Bitcoin prices were unreasonably high at $50. Does that mean that Bitcoin prices “must come back down” to a level far below $50?

Human: Time will tell. In any case, I’m not claiming the experts are invariable right; rather there are clear cases where experts are able to spot a “what goes up must come down” situation, such as stock market bubbles.

Alien: I’m listening.

Human: For instance, in the late 1990s, experts like Alan Greenspan and Robert Shiller spotted irrational exuberance in the stock market. They saw that prices had skyrocketed to unreasonable levels.

Alien: How did they know that prices were irrational?

Human: Robert Shiller constructed a model that suggested stock prices were excessive when P/E ratios exceeded a certain threshold.

Alien: How did he know that this model was useful?

Human: It fit past data quite well. If people had invested on the basis of his model then they would have outperformed the market during the 20th century.

Alien: OK, his model “predicted” the past, but what about the future? When did Greenspan and Shiller first claim that the market showed irrational exuberance?

Human: In 1996.

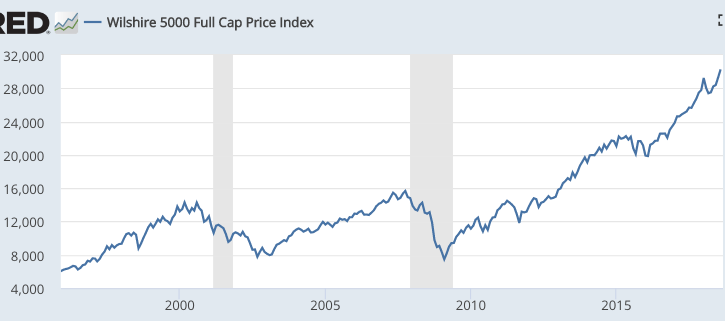

Alien. Can you show me a graph of the stock market during the period since 1996?

Human: This is a fairly comprehensive stock market index:

Alien: I’m confused. Weren’t they saying that prices in 1996 were far too high, and must come down to a level seen in previous years? When did stocks “come down” from 1996 levels?

Alien: I’m confused. Weren’t they saying that prices in 1996 were far too high, and must come down to a level seen in previous years? When did stocks “come down” from 1996 levels?

Human: Well, they were a bit early in the bubble call, but there certainly was an irrationally high peak in 2000, after which prices came down sharply.

Alien: OK, but then aren’t we back to your original claim, that when asset prices rise to a peak and then fall it shows that what goes up must come down? Again, is this a claim about how the world behaves, or is it a description of mountain peaks?

Human: I think you are taking this all too literally. No one claims that the experts are always right, but there are cases where the market is clearly overvalued.

Alien: So you are saying that there is a class of experts who are smarter than the markets, who are able to avoid irrational exuberance. They cannot predict perfectly, but they can do better than the market consensus.

Human: That’s right.

Alien: OK, so would I be correct in assuming that these very smart experts were not invested in stocks during 2000, when the market was clearly overvalued?

Human: Well . . .

Alien: And did these experts encourage people to buy stocks in 2002 and in 2009, when prices were at very low levels?

Human: Actually, most experts recommend that people try to avoid “market timing” and just invest for the long run.

Alien: I’m still confused by all this, so I searched the internet and found an example of Robert Shiller offering investment advice in June, 2015:

Still, Shiller says, people are right to invest in U.S. stocks. “I’ve been talking down US stocks because of their high valuation, but I would invest something in US stocks,” says Shiller. “It’s been an amazing run and looks like something that can’t keep going indefinitely, but it might continue for several more years,” he says, adding that no one knows when it will end and it “might end very badly.”

Human: See, Shiller turned out to be pretty smart.

Alien: Yes, although he suggested that stocks were overvalued in January, 2011, so there is evidence both ways. But I’m more interested in his reasoning process. Isn’t Shiller saying that his model predicts that stocks are overvalued, but he recommends buying them anyway because, well, maybe this crazy rally has even a bit more room to run?

Human: Well, he was right, wasn’t he?

Alien. Yes, but he was right in 2015 because he engaged in exactly the sort of “irrational exuberance” that experts are supposed to avoid, whereas he was wrong in 2011 because he adhered to his “rational” model. So I’m still a bit confused by these “experts”. Are they really any more rational than the average investor? Are they any more successful?

Human: Warren Buffett has been very successful.

Alien: (Frantically searches the internet). Ok, here’s what I found out about Warren Buffett.

1. He doesn’t seem to believe in market timing. He often held lots of stocks at points in time that experts later called bubbles. He lost lots of money when prices subsequently fell.

2. He bet a famous investor that experts such as hedge fund managers could not consistently beat the market.

3. He easily won the bet.

Here’s what we noticed when we first visited Earth. Your financial market media was full of graphs of asset prices. We did not understand your economy, but noticed that these graphs look a lot like what we call a “random walk”. We know that when a random walk goes up, it is not true that it “must” come down. But we also know that when a time series follows a random walk, there will almost inevitably be periods of upward trending prices, followed by periods of downward trending prices, merely by chance.

We first assumed that your asset prices followed a random walk, but the “what goes up must come down” commentary suggested that we were wrong. I have to say that after discussing this with you I’m inclined to go back to my original assumption—asset prices follow random walk.

Do you have a volunteer to undergo a brain scan? One of our scientists speculates that evolution on Earth may have favored people with a strong tendency to engage in pattern recognition, and that humans might have evolved to the point where they see patterns that are not really there. She thinks this is because pattern recognition would have been extremely useful to humans in the era before there were asset prices following random walks.

Human: I’ll look for a volunteer.

READER COMMENTS

Joe B

Sep 5 2018 at 5:03am

This is great. L

Alan Goldhammer

Sep 5 2018 at 8:13am

Scott – Well Done!!! Time to go back and watch the great movie with David Bowie.

Philo

Sep 5 2018 at 9:22am

What goes up *to a peak* must come down (by the definition of ‘peak’).

Robert EV

Sep 5 2018 at 11:00am

The alien knows crap about physics.

“Up” and “Down” only having meaning in relation to the local gravity well. Go ‘out’ past Earth enough and you are in the Sun’s gravity well, not the Earth’s. Go out fast enough and you aren’t going “up”, you’re going ‘out’. The surface of the earth and the space probe become the equivalent of a coastline and a ship.

Eventually it will “come down”. The universe is not infinite in time (or reachable space), after all. There’s just a lot of room for wiggling until it gets there.

Dennis

Sep 5 2018 at 2:39pm

I like this, but I think you are conflating a number of ideas here. Prices are correct in the sense that Prices = fundamental values necessarily implies that you cannot make excess profits in the market. But the reverse is not true. Just because you cannot make money in the market does not mean that prices are correct. Transaction costs, hedging risk, short restrictions, noise trader risk can all eliminate excess profits. We have seen clear examples of market irrationality like the spinoffs during the 90’s.

Also prices = fundamental values have nothing to do with prices being predictable. We would expect P/E ratios to predict returns in a perfectly rational world. If risk-aversion increases, a basic pricing model (P=E(1+g)/(1+r)) tells us that expected returns will go up and P/E will predict returns.

Scott Sumner

Sep 5 2018 at 4:18pm

Alan, Yes, a fine movie.

Dennis, This post is not about fundamental values, it’s about “what goes up must come down.”

Michael w

Sep 5 2018 at 9:04pm

This is also about the concept of heuristics; the alien can save his research for another time and just read Thinking Fast and Slow; though alternatively he might find that Kahnemann would make an excellent research partner in this endeavor.

Comments are closed.