In 2021, some economists predicted that high inflation would be transitory. When inflation soared much higher in 2022, those claims looked foolish. Now that headline inflation has fallen to just over 3%, some are asking whether inflation was transitory after all.

Macroeconomic data never “speaks for itself”. Data only has meaning in the context of a model. In order for transitory inflation to have a useful meaning, we need to consider how nominal and real variables interact.

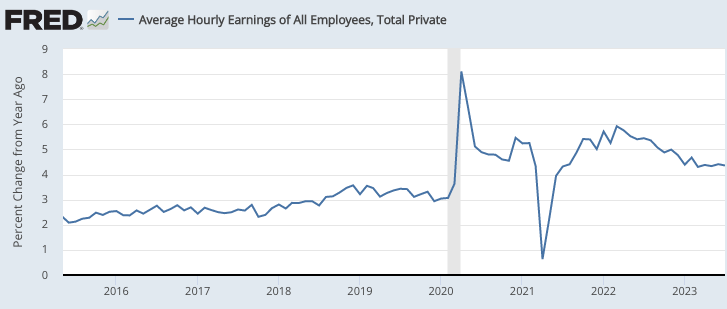

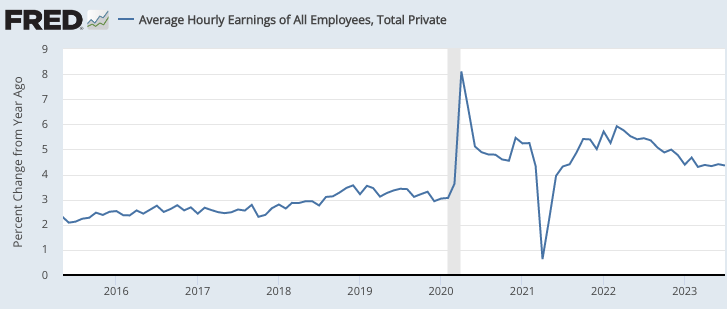

The average person probably views the concept of “transitory” in terms of a specific period of time—a few months, or perhaps a year. In my view, that’s not a useful way to define the term. Instead, it is more helpful to view transitory inflation as being associated with no change in the growth rate of nominal wages (allowing for composition effects.)

For example, suppose there is a terrorist attack that shuts down the Saudi oil industry for a couple of months. Oil prices would rise and the Fed would probably allow some increase in the overall CPI. When Saudi oil comes back onto the market, oil prices would fall and the CPI would fall back to trend. Nominal wages would be largely unaffected. This is roughly what people have in mind by the term ‘transitory’.

In my view, the most useful definition of transitory is not the period over which the higher inflation persists, rather whether or not it bleeds through to wage inflation. As long as nominal wage growth is stable, all excess inflation is likely to be transitory, whether lasting for 3 months or 3 years. In contrast, if nominal wages start accelerating, then inflation will remain elevated unless a contractionary monetary policy brings wage growth back to normal. Throughout history, that has usually required a period of elevated unemployment (although a “softish landing” is not inconceivable if the disinflation is gradual.)

From this perspective, there is no specific time frame that makes inflation transitory. Any significant amount of elevated wage inflation, no matter how short in duration, constitutes non-transitory inflation. Of course the term “significant” is open to interpretation . Macro data is noisy, and a single month’s data might reflect random shocks, not an overheated labor market. Nonetheless, the criterion here is not the duration of the labor market overheating; the existence of any significant excess nominal wage growth constitutes non-transitory inflation.

During the period of Covid shutdowns, the BLS wage data was thrown off by “composition effects”. Even if every single person got a completely normal wage boost during 2020 (say 3%), the average wage growth would have looked high because lower wage workers were disproportionately laid off.

In a case such as 2020, nominal GDP growth would be an alternative indicator of non-transitory inflation. By late 2021, NGDP was rising above the pre-Covid trend line, and hence by that time inflation was no longer merely transitory.

PS. I’m seeing some optimism that the labor market is normalizing, with pundits pointing to things like lower quit rates and fewer unfilled jobs. I hope these pundits are correct. But keep in mind that the real problem is nominal. We still need to bring nominal wage growth back down to 3%. Various real labor market indicators will eventually normalize (at their “natural rate”) even if nominal wage growth stays permanently elevated. That was Milton Friedman‘s great insight in the late 1960s. (Also Edmund Phelps.)

READER COMMENTS

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 10 2023 at 3:28pm

“In order for transitory inflation to have a useful meaning, we need to consider how nominal and real variables interact” Agree but I’d add “in the contest of Fed settings of its policy instruments.”

Focusing possible disequilibria in relative prices only on wages — a highly heterogeneous aggregated for which we have poor observations (usually unit value indices instead of wage indices) — seem odd.

Rajat

Sep 10 2023 at 7:08pm

I think this could use a bit of clarification. The ‘bleeds’ point in the first sentence suggests that you see wage inflation as a good proxy for the measure of nominal demand most relevant for macroeconomic stability (ie for a stable labour market). That’s how I understood your framework. But the following two sentences suggest that wage inflation somehow ’causes’ price inflation, which seems to be how some economists (including the departing RBA Governor!) and journalists view the Phillips Curve relationship. Would you mind commenting?

The way I have been thinking about the transitory question is that if inflation appears to be slowing back towards the target – but not undershooting for any length of time – and this has coincided with significant increases in policy interest rates, then the obvious inference is that the inflation was not transitory. It required monetary policy action, noting that higher rates per se do not imply tighter policy. One-off real shocks (assuming these were not accompanied by money demand shocks) would only cause short run increases in annual CPI inflation even with a constant policy interest rate. Would you agree?

Scott Sumner

Sep 10 2023 at 11:26pm

No, I don’t view it as wage inflation causing price inflation, rather both are caused by monetary policy (and other factors.) My point is that the sort of monetary policy that causes wage inflation will also make price inflation almost inevitable.

You may well be right about interest rates, but I’d hate to generalize given how unreliable they are as a policy indicator.

Matthias

Sep 10 2023 at 8:06pm

The compositional effects during COVID only come up because you are looking at something like the wage for the average employed worker or so?

What if you took the total nominal wages without dividing by the number of worked hours? (Or if you divided them by the number of working age adults?)

Or do these alternative measures have other problems?

Scott Sumner

Sep 10 2023 at 11:27pm

Total wages are another good monetary policy indicator, although this was also affected by Covid.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 11 2023 at 11:48am

I don’t get “indicator of policy.” important datum to be used to set policy instrument values? But why focus on any one datum?

Rafael

Sep 11 2023 at 2:41pm

Professor, in the past I asked a similar question about why you focus on hourly earnings rather than total payrolls and you very politely answered on your preference.

Since then I’ve done a bit more work on the subject and believe that total payrolls are a less noisy indicator. I believe AHE are quite noisy as they tend to be moved more by the denominator (hours worked) rather than the numerator.

If you look at the correlation of YoY change in hours worked during the post-GFC ‘stable growth’ period (2013-2019) there’s a large negative correlation between total payrolls and AHE which I think provides evidence for the above hypothesis.

I think this is pretty important from an analytical point of view as there is currently a large difference between AHE (~4,3%) and Total Payroll growth (~2%) suggesting very different paths for policy.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 12 2023 at 8:19am

The more fundamental problem is that hourly earnings is not a wage index. It does not compare the wage (or wage plus benefits) a representative sample of jobs. Like other unit value indexes, it is affected by the composition of jobs that varies from period to period.

Scott Sumner

Sep 12 2023 at 11:17am

This is not my area of expertise, but the 4.3% figure seems much more accurate than the 2% figure, given the current condition of the economy.

Brandon Berg

Sep 11 2023 at 3:08am

To elaborate a bit on this, I think that different people are using “transitory inflation” to refer to different phenomena.

One definition of transitory inflation is a brief period of elevated inflation, after which inflation returns to the desired level. We’re at 2% inflation, then over a period of a year or so it spikes to 10% and returns to 2%. In this scenario, while high inflation is transitory, the price level’s upward deviation from the earlier trend is permanent.

Another definition, the one you’re using in this post, is a brief elevation in the average price level, after which prices return to the trend they had been following earlier. In this scenario, the price increases themselves are transitory, and the period of high inflation is followed by a short period of benign, supply-side deflation, bringing the price level back to trend.

Of course, it’s possible for the central bank to induce deflation with contractionary monetary policy in an attempt to compensate for excessively expansionary monetary policy in the past, but this would be an unforced error, so as a rule demand-side inflation follows the first pattern and supply-side inflation follows the second pattern.

Andrew_FL

Sep 11 2023 at 9:38am

Returning to trend does not require deflation. It simply requires a period of below 2% inflation. It is only that the further from trend you get the longer such a period needs to be. How much below 2% you have to go depends both on how far from trend you are and how quickly you are comfortable getting back to the 2% trend line. Any below 2% rate, the 2% trend line will catch up to eventually.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 12 2023 at 8:27am

This takes Flexible Average Inflation Targeting too literally. The “average” here means that if the Fed has the instruments set for 2% it does not panic if one month comes in a little above or below. But if it allows inflation to get seriously above or below target it will adjust instrument settings as necessary to again get onto a 2% trajectory. It should not be backward looking to compensate with below/above target inflation.

Andrew_FL

Sep 12 2023 at 10:14am

I didn’t say anything about FAIT. But yes, under your and the Fed’s “Flexible Average Inflation Targeting”, the price level is allowed to permanently drift upwards or downwards whenever the Fed makes a serious policy mistake.

Scott Sumner

Sep 11 2023 at 12:35pm

As long as wage inflation doesn’t accelerate, prices should return pretty close to the original trend line.

John Hall

Sep 11 2023 at 8:24am

“During the period of Covid shutdowns, the BLS wage data was thrown off by “composition effects”. ”

The employment cost index is less susceptible to these issues. You can also look at the total wage bill.

Kevin Erdmann

Sep 13 2023 at 2:31am

Hey Scott. I posted some notes on current policy that included some comments about your post. Here’s the link, in case you might be interested in reading it. It looks like the FT has linked to it this morning.

https://kevinerdmann.substack.com/p/inflation-everyone-is-right

Scott Sumner

Sep 13 2023 at 2:42pm

Thanks. Very good post. My only quibble is that the Fed seems to be determined to stick to 2% as its inflation target. If so, we’ll need no more than 4% NGDP growth. A 5% target would deliver 3% inflation.

Comments are closed.