There’s a debate about whether LLMs such as GPT-4 have some sort of consciousness. That is, are they able to think, analyze, understand, etc., in a way that is somewhat analogous to how the human mind works? Back in 2022, Gwern argued that LLMs have agency:

Powerful generative models like GPT-3 learn to imitate agents and thus become agents when prompted appropriately. This is an inevitable consequence of training on huge amounts of human-generated data. This can be a problem.

Is human data (or moral equivalents like DRL agents) necessary, and other kinds of data, such as physics data, free of this problem? (And so a safety strategy of filtering data could reduce or eliminate hidden agency.)

I argue no: agency is not discrete or immaterial, but an ordinary continuum of capability, useful to a generative model in many contexts beyond those narrowly defined as ‘agents’, such as in the “intentional stance” or variational approaches to solving physics problems.

Thus, a very wide range of problems, at scale, may surprisingly induce emergent agency.

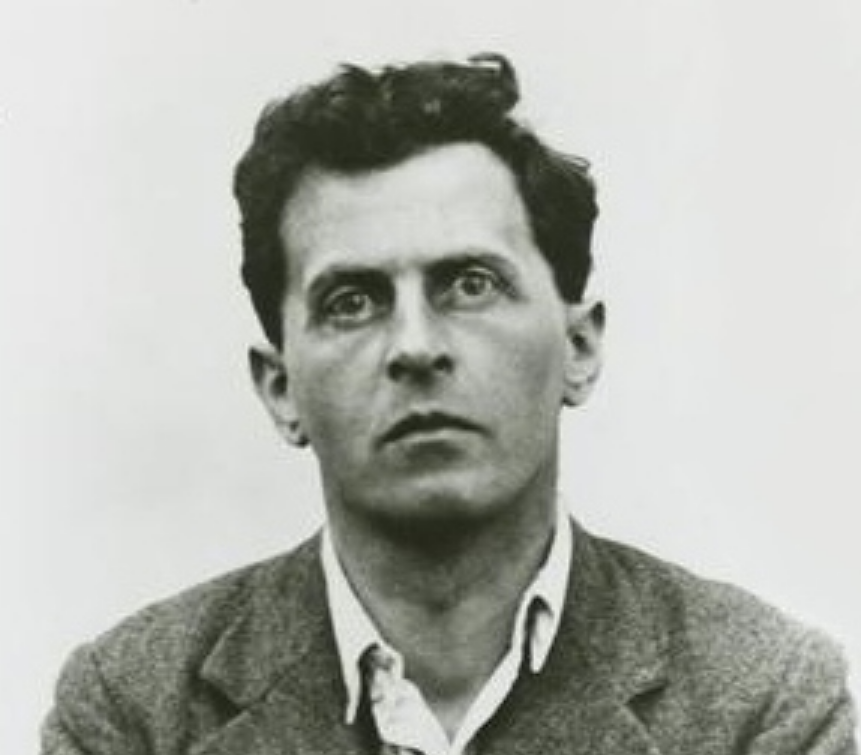

At one point he referred a famous anecdote attributed to Ludwig Wittgenstein:

He once greeted me with the question: ‘Why do people say that it was natural to think that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth turned on its axis? I replied: ’I suppose, because it looked as if the sun went round the earth.’ ‘Well,’ he asked, ‘what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the earth turned on its axis?’

He is asking those who are skeptical of LLMs having agency to consider what their behavior would look like if they did have agency.

When I first discovered the Wittgenstein quotation, I immediately recognized that it almost perfectly illustrated the point I was trying to make about the crisis of 2008 being produced by tight money. Indeed I used the quote as an epigraph for my book entitled The Money Illusion.

It occurs to me that Wittgenstein’s insight has many applications in economics. Consider the following examples:

1. Economists often argue that the US current account deficit is caused by low rates of domestic saving. In contrast, for many people it looks like the deficit is caused by US firms being unable to compete with cheaper foreign rivals. One response to those with this common sense view might be: What would it look like if it looked as if a lack of domestic saving caused the exchange rate for the dollar to appreciate strongly enough to where many US firms were no longer competitive with foreign rivals?

2. Economists often argue that the US benefits from importing foreign goods. In contrast, to many people it looks like imports hurt the US economy by negatively impacting domestic firms that compete against imports. One response to those with this common sense view might be: What would it look like if it had looked as if international trade caused the US economy to reorient production toward goods in which we have a comparative advantage, boosting total output?

3. Economists often argue that inflation is caused by the effect of monetary policy on aggregate demand. In contrast, to many people it looks like inflation is caused by greedy firms raising prices and boosting profits. One response to those with this common sense view might be: What would profits look like if it had looked as if monetary policy caused aggregate demand to rise sharply at a time when nominal hourly wages were sticky?

The Money Illusion is basically a long examination of why I believe the Great Recession was caused by tight money, rather than housing and banking problems. Step by step, I show that the facts fit the tight money explanation far better than the conventional view. I show that all of the stylized facts that are typically viewed as causal factors are actually better viewed as the consequence of tight money. I also showed that the conventional view is inconsistent with most stylized facts, such as the fact that the sharp economic slump began several months before Lehman failed and the fact that the Great Recession was worse in Europe, despite the subprime crisis being in America. (Europe had tighter money.) And before you try to come up with an ad hoc explanation for those anomalies, recall that (in 2008) conventional economists almost universally expected the Great Recession to be worse in America, because they were working with the wrong model of the economy.

A geocentric model of the solar system with epicycles may work for a while, but with a close enough examination of the data you’ll eventually find anomalies. And I found dozens of inconvenient anomalies. Read the whole thing:

READER COMMENTS

Matthias

Nov 28 2023 at 9:12pm

Nice seeing you engage with Gwern’s body of work, Scott!

As for the very geocentric example:

On a small, human scale, you get dizzy when you twirl yourself around and you clearly notice centrifugal/centripetal forces as such.

If we noticed these on earth with our unaided senses, we would definitely have thought of a rotating earth as more ‘natural’.

In this case, naively extrapolating from everyday experience leads us astray. And perhaps a similar thing is happening with ‘greedflation’.

Especially because many transactions are like an iterated prisoner’s dilemma or ultimatum game: if I’m already at the supermarket, I’m gonna buy some milk and eggs, even if they are 100% more expensive than the prevailing price. But I’m gonna bad mouth the supermarket afterwards to my friends and perhaps in online reviews.

The human psyche has evolved strong strategies and precommitments to these kinds of situations. So we can’t shut those off, even if intellectually you could make an argument that greedflation is nonsense.

Have a look at the experiments done with the ultimatum game: even if it’s not repeated, people are still likely to reject anything but (something close to) a 50:50 split.

That tendency is so strong, that it can count as a credible precommitment, thus making sure most people get a better offer in the first place.

Henri Hein

Nov 29 2023 at 12:18am

I am fascinated with the Google Pirates problem, so I looked into the Ultimatum Game myself, as it is the closest equivalent experiment. One thing about it is that it is culture dependent. Americans are more likely to both offer and accept a lop-sided proposal. Offers are less lop-sided in Europe. In China, even a 55:45 offer is rare and almost never accepted.

One experiment tried to buck the trend. A problem with most of the experiments is that the sums are often trivial, or at least not substantial. That makes spite cheap. To get around this, someone ran an Ultimatum Game in an area in rural India with low wages. The offered sum were several months worth of wages for the median earner in the locale. In addition, they added verbiage to point out that a lop-sided offer is likely to increase the payout for the proposer. The result was that lop-sided offers were the norm, and they saw more extreme lop-sided offers like 90-10. Lop-sided offers were also more likely to be accepted. What is interesting to me is that the median successful offer was still something like 70-30 or maybe even 65-35 (don’t remember the exact number off the top of my head). A substantial portion of the 90-10 offers were still rejected, and you didn’t see the 99-1 offers at all, like the Google Pirates problem predicts.

Scott Sumner

Nov 29 2023 at 11:51am

Good points.

Henri Hein

Nov 29 2023 at 12:42am

I bought The Money Illusion a while ago, but it disappeared in a move. I’m looking forward to a treat when I come across it in a box or the back of a shelf sometime.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Nov 29 2023 at 10:58am

I think it is confusing to contrast monetary policy and poor financial sector regulation as “causes” of the Great Recession. I don’t dispute that “better” monetary policy might have avoided the financial crisis in 2008, but surely THAT error pales in comparison to allowing inflation expectations to go NEGATIVE in late 2008-09 and STAY below target for most of the decade, never to have announced a “whatever it takes” policy to get inflation temporarily above target to adjust to the shock of the crisis and then keep it on target.

I find the refutation of the “commonsense” fallacies more confusing than the straightforward explanation of the correct position.

Warren Platts

Nov 29 2023 at 3:38pm

Didn’t Bernanke once say that the root cause Great Recession was the global savings glut? (Excess savings, by definition, exceed productive investment opportunities, and are thus forced into non-productive assets like home loans to people who can’t repay them, thus eventually causing a banking crisis.)

Warren Platts

Nov 29 2023 at 3:34pm

Wait a sec. These both can’t be true. If it’s the case that we have a trade deficit because US firms are not “competitive”, then, clearly, the free trade caused reorientation of production toward “comparative advantage” that is supposed to boost total output is not working out as advertised. And vice versa.

However, both can be false. It could be the case: (1) that the trade deficit is caused by a foreign savings glut among the mercantilist states; and (2) free trade has not boosted total output.

Of the former, it is just a matter of logic: in a closed economy S = I, and Planet Earth is a closed economy. Thus if in one country S > I, then, by definition, it must be the case that S < I in another country. And since the foreign savings gluts are caused by deliberate, foreign governmental policy, whereas in the United States, being the chumps that we are, since we want free trade of goods and services, we also want free trade in capital (money). Therefore, a trade deficit is bound to happen. (Moreover, the trade deficit is not a proof that the USA does not also save too much.)

Of the latter, I always like to say that the quickest way to stump a free trade economist is to ask them what a continental-sized economy like the USA ought to specialize in; but just judging by our top exports, our comparative advantage is in things like petrochemicals, soybeans, nonferrous metals, and weapons. With the exception of weaponry (the only sector where the U.S. makes a serious effort to protect its IP), these are mostly hyperproductive (non-labor intensive) raw materials producing industries. However, adding value to raw materials through manufacturing tends to be comparatively labor intensive. Thus the process of labor arbitrage in tradable industries tends to force American workers out of relatively productive, tradable, labor-intensive industries into nontradable, less productive, labor-intensive service sectors. The result is a net loss in labor productivity compared to what it otherwise would be, thus causing a strong headwind for economic growth. (I’ll note that the average real GDP growth rate for the USA is about a third less than it was prior to the era of hyper-globalization.)

Scott Sumner

Nov 29 2023 at 9:35pm

You’ve certainly packed a lot of fallacies into one post. Here are just a few:

“And since the foreign savings gluts are caused by deliberate, foreign governmental policy,”

It’s not that foreigners save too much, it’s that we save too little.

“the United States, being the chumps that we are, since we want free trade of goods and services, we also want free trade in capital (money).”

We are one of the most protectionist economies in the world, at least among developed countries.

“However, adding value to raw materials through manufacturing tends to be comparatively labor intensive.”

That was once true, now it’s capital intensive.

“The result is a net loss in labor productivity compared to what it otherwise would be, thus causing a strong headwind for economic growth.”

The exact opposite is true. Your “chumps” have a higher per capita output than most countries with surpluses.

Bob

Nov 29 2023 at 9:58pm

The general public is often a buyer, but rarely a seller of goods that are a part of a bidding war. The idea that production is limited, and therefore raising prices allocates goods to those that want them the most is just weird to them.

It even happens for people that should know better, like someone renting apartments over the summer. I’ve had trouble convincing someone that yes, instead of dealing with people building bots to be able to rent the best apartments in town the moment they are offered for the seasont, that he should instead raise prices.

Greg G

Nov 30 2023 at 5:43am

Great post Scott. I’m not always sure that I agree with you but I never doubt that you are one of the most original thinkers and best teachers in economics today.

Scott Sumner

Nov 30 2023 at 6:40pm

Thanks Greg, I appreciate it.

spencer

Nov 30 2023 at 8:43am

Yeah, the pundits suffered from the lag effects of retrocausality.

mira

Nov 30 2023 at 10:02am

Good news this morning re: rate cut signaling – looks like the Fed is waking up to the fact that the last little bit of inflation might be more difficult to stamp out.

Are you with Wittigenstein-cum-Gwern on LLMs?

rafael

Nov 30 2023 at 2:39pm

This got me thinking in that it applies perfectly to the whole “inflation was supply chain related” theory.

Well, if it had been due to easy money and too much spending it would look like factories were not able to meet demand as they had more orders than they were able to fill and obtain raw materials for.

In other words money related inflation looks *just* like “supply chain issues” related inflation. Its just the ‘issues’ were caused from too many orders rather than covid related “disruptions”

Scott Sumner

Nov 30 2023 at 6:39pm

Yes, those West Coast port “bottlenecks” were not caused by supply problems, they were caused by record imports related to stimulus spending.

Lizard Man

Nov 30 2023 at 7:06pm

At least in the early part of the pandemic it was a case of output falling while nominal spending didn’t fall. Granted that one of the reasons that nominal spending kept growing even while output fell was monetary policy. If it is strictly monetary policy causing the inflation you shouldn’t see real output fall. The pandemic was definitely a negative supply shock.

Rafael

Dec 2 2023 at 7:33pm

There definitely was an immediate negative supply shock in the initial lock down phase. But that was basically over and reversed in a quarter or two. From late 2020 on there was no longer a negative supply shock

Knut P. Heen

Dec 1 2023 at 9:43am

I use the Wittgenstein quote on my first slide in a business economics class I teach (before I go on to explain the benefits to society of profit maximization).

MarkW

Dec 1 2023 at 11:33am

BTW, no LLMs aren’t sentient. They have no ‘inner monologue’. No qualia. No daydreams. No hopes. They do no ruminate. They are never bored, frustrated, fatigued, or confused. They incorporate information about everything — including information about what agents do. So they can mimic agents by producing outputs that actual agents might. But they have no agency. LLMs are effectively ‘P-Zombies’ brought ‘to life’.

Comments are closed.