In a recent post, I expressed skepticism about the ability of anyone to meaningfully predict the outcome of military engagements. There are many factors that make accurately predicting this sort of thing all but impossible, but one factor that deserves to be kept in mind is the impossibility of military planners to have all the relevant information.

As one studies military history, one thing that jumps out is how major events turned on tiny details. In the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Trenton, while not a large engagement, was still a pivotal moment. The victory for the American forces was a major morale booster and encouraged more Americans to join in the war efforts. And a crucial component of this victory was that George Washington’s forces held the element of surprise, with the famous crossing of the Delaware River. They caught the Hessian forces completely off guard and were able to secure a quick victory with minimal losses. How differently might history have gone if, instead of holding the element of surprise, Washington and his forces had been spotted, and attempted to attack a garrison that was fully expecting them?

Except, Washington and his forces absolutely were spotted and seen coming. A British sympathizer saw their approach and promptly reported it. This report was carried to the garrison and given to the commander of the outpost who, engrossed in the card game he was playing, promptly put it in his pocket and forgot about it. Had the commander, in that one brief moment, decided to look at the report rather than put it in his pocket, Washington and his forces wouldn’t have been moving towards a successful surprise attack – they would have been walking straight into an ambush. And how differently might that battle have gone, and from there, the entire course of the Revolutionary War? One brief moment, one small decision, and the future of the world is forever changed.

These kinds of lynchpin moments can only be identified in hindsight – and even then, we have no idea just how many equally crucial moments have occurred but never made it into any history books. Others are simply unknowable by their nature. Imagine another world where the garrison commander was in a more professional mood that night and would have promptly opened the letter and been prepared for the attack – but the British sympathizer who sent out the initial warning had died of smallpox as a nine-year-old. That small child’s death would have equally been such a lynchpin moment, but there is no way for historians to know this and record “if this little boy had grown into an adult, he would have spotted the forces of the rebellion and alerted the nearby garrison, forever changing the direction of the war.”

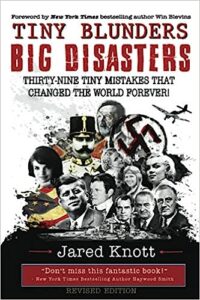

An entertaining book filled with these kinds of moments is Tiny Blunders/Big Disasters: Thirty-Nine Tiny Mistakes That Changed the World Forever. It chronicles a series of small, seemingly insignificant moments and decisions that ultimately led to massive consequences, such as when a “soldier accidentally kicks a helmet off of the top of a wall and causes an empire to collapse.” The more you study history and learn about how many major, world changing events turned on tiny details, the more you appreciate how utterly impossible it is for large-scale social planning to be carried out effectively. These aren’t cases where you can say “if only someone wiser had been in charge, if only the planners had been better informed, these circumstances would have been anticipated and the outcomes been kept under control.” History turns on events that nobody can and ever could anticipate or see coming, and nobody can possibly plan or control for.

This doesn’t just apply to large scale, society level planning. Even in our own lives, there are seemingly tiny moments where small, trivial decisions later turned out to be the moments where everything changed – and only in retrospect can we see what those moments were. And we’ll never, ever know how many such moments occurred that we can’t identify – or how our lives would look today if any of those moments went differently. I’ll give one personal example. I never would have met my wife, and thus my children would not exist today, if, six months before she and I met, and while she was thousands of miles away on a different continent, on one specific night, I hadn’t decided to stop at the smoke pit in front of the barracks briefly before heading off base to get something to eat.

There is no planner in the world who can identify and integrate these kinds of moments into their plan – and thus there is no planner in the world who can craft a plan that will turn out as they expect. As I once heard George Will quip, Elizabeth Warren’s favorite catchphrase is “I have a plan for that” for any and all social issues – but there is much wisdom in the old saying “If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans.”

READER COMMENTS

steve

Jul 15 2023 at 9:47am

I think we call this luck. Bad luck, good luck can change outcomes, but only if people are prepared to act when it happens ie they had a plan and part fo that planning allowed them to adapt. Military history certainly shows that generals/kings who did not plan or prepare nearly all failed. They might have won a few battles due to overwhelming numbers, but they are the exceptions. The Romans didnt win so many battles for so long due to lack of planning. When faced with a military genius like Hannibal they changed tactics and planned differently.You can make a good case that the most important general for the US in WW2 was Marshall and his planned logistics, training and prep.

So good planning usually wins. That doesnt mean all plans work. Some dont. Could be bad luck, bad plan or other guy had a better plan. To that you should add Boyd’s theory that in war having the better moral cause/morale is also important. Almost, maybe more, as important is the ability and willingness to adapt plans. Rigidly adhering to plans has lost a lot of battles.

Steve

steve

Jul 16 2023 at 2:15pm

Shame on me, I forgot the details for Battle of Trenton. It is true that the Hessian commander received information but people forget that it had been arranged that Abraham Hunt would entertain the commander and his other senior officers that night. Hunt pretended to be a loyalist and his role was to keep them distracted. That plan worked. Your cited example is actually a very good case of successful planning.

So at least in the military, most plans also have contingency planning and back up preparations have been made. It’s why throughout history you find that some generals consistently won battles and others did not. There is good evidence that central planning isn’t a good idea broadly for government but the metaphor here doesnt hold very well.

Steve

Jon Murphy

Jul 16 2023 at 5:30pm

I wouldn’t. There’s no element of chance. The commander made a decision. That decision backfired monumentally.

David Seltzer

Jul 15 2023 at 3:21pm

Kevin: A history professor said to me, “I know that all times, history draws the highest consequence from remotest cause.” Mandelbrot informed us of sensitive dependance on initial conditions wherein a small change in one state of a nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state. Errors propagate nonlinearly.

Monte

Jul 15 2023 at 4:07pm

If only Longstreet had followed Lee’s orders to attack the Northern Army at sunrise on July 2, 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg would have been won and, with it, Southern independence.

If only Secretary of State Cordell Howe hadn’t ignored Ambassador Joseph Grew’s warning of Japan’s plans to attack Pearl Harbor, that attack would have been thwarted.

If only OceanGate CEO Stockton had listened to Liz Taylor, president of DOER Marine Operations, the Titan submersible tragedy could have been avoided.

Perhaps. Whether we choose to believe events unfold by chance or the guiding hand of Divine Providence, Robert Burn’s aphorism stands:

Robert EV

Jul 16 2023 at 11:12am

“the Battle of Gettysburg would have been won and, with it, Southern independence.”

Or it would have continued for another 5 years.

Or Sherman would have marched a year early.

Or the British and Canadians would have materially sided with the north to end slavery.

Who the hell knows.

“that attack would have been thwarted.”

…wouldn’t have been as bad. We know from our own history (US revolutionary war) that even mild subjugation of peoples by foreign powers will often lead to war. Yet we, the US, keep doing it!

“If only OceanGate CEO Stockton had listened to , the Titan submersible tragedy could have been avoided.”

They would have done better screaming it aloud to the potential customers. James Cameron, for one, could have absorbed the resulting lawsuit damages, presuming

Heaven’s GateOceanGate would have won their defamation claim.Robert EV

Jul 16 2023 at 11:18am

To your point, former general, then President Eisenhower thought overthrowing democratically elected governments was a good idea to stop the spread of communism, when just a little over 30 years later the main communist empire collapsed. And the second largest communist power basically became, in some part, the same sort of authoritarian-led, semi-capitalist society that replaced those democratic governments which were overthrown.

The best that knowledgeable people can predict, when it comes to the outcome of actions by other people, is how those people will psychologically respond to any particular outcome. As you say, we certainly can’t predict particular outcomes. Not over a long enough time, or when sufficient numbers of people are involved.

Comments are closed.