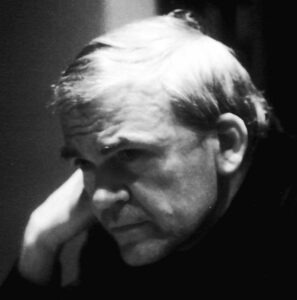

When the dust will settle, I am sure that Milan Kundera will have a place among the greatest novelists of the last century. His prose was magnificent, his stories well built, his sensibility unique. Kundera defended the novel as the cornerstone of European culture but was quite alert to a vice practiced by most literati: their tendency to take sides, to use culture as a Trojan horse for some “view” or “opinion”, their eagerness to celebrate political power, even in its cruelest moments.

Kundera claimed the novel as a way to make present justice, since as human beings we have difficulties in living the present: we look forward to the future, we long for the past, we play with our memories. This meant that the novel for him was the quintessential space of freedom: it should not be twisted into propaganda, of any kind, nor be appreciated because of the views it conveys.

This may explain one of the features of Kundera’s work that I find more attractive. His characters may be voluptuous, or crazy, or weak, or stupidly bold, or mad. They may be lying, betraying, running away. Yet he described all their imperfections with a light touch, a true sign of appreciation for humanity as it is. He didn’t like labels, and insisted not to be attached any. But, in this sense, he had a sensibility which I think should be particularly attractive to classical liberals – or at least it is to this classical liberal.

I read a few tributes to Kundera, who died on July 12 at 94 years old. The best one is this truly excellent piece by David Samuels for Unherd.com. Here’s a bit:

Kundera was never particularly interested in or engaged by politics. Instead, his work was a passionate defence of the right to pursue one’s own individual desires and lusts against bureaucratic maniacs of whatever stripe who wished to colonise individual experience on behalf of the state. To his critics on both the Right and the Left, Kundera’s stance was borderline immoral, not to mention hopelessly bourgeois. While the Left preferred Che and the Right preferred Solzhenitsyn, Kundera insisted on the human right to be left alone.

As alienating as Cold War ideologues found Kundera’s bourgeois anti-politics, there were also plenty of writers and critics who objected to the qualities of his prose. The intense musicality of his sentences could seem like an artefact of a romantic moment that had passed. His world-class talent for aphorisms could seem similarly dated, a parlour trick that impressed college students on their junior year abroad: “there is no perfection only life” (The Unbearable Lightness of Being); “to laugh is to live profoundly” (The Book of Laughter and Forgetting). He objectified women, in a way that grew increasingly detached from dominant Anglo-Saxon sensibilities. Surely the world had better things to do with its time than to vicariously wallow in the lusts of yet another ageing male writer.

Kundera never saw himself as a political man, as a moralist, a liberal, a conservative, or as an author of texts whose highest destiny was to become movie scripts. He was, quite simply, a novelist. For him, the novel was the highest form of aesthetic endeavour, a kind of anti-scripture representing the sensibility of the individual, containing “an outlook, a wisdom, a position; a position that would rule out identification with any politics, any religion, any ideology, any moral doctrine, any group”. The faith he placed in the novel as a compass that can be used to negotiate life’s big questions can seem hopelessly antiquated. Yet if you don’t believe that, why bother to write one?

Read the whole thing, it’s worth it.

READER COMMENTS

Scott Sumner

Jul 14 2023 at 11:25am

Very nice comments. In addition to writing great novels, he was also a very talented essayist. In the following quotation, you could replace “Europeans” with “liberals”:

“Suspending moral judgment is not the immorality of the novel; it is its morality. The morality that stands against the ineradicable human habit of judging instantly, ceaselessly, and everyone; of judging before, and in the absence of, understanding. From the viewpoint of the novel’s wisdom, that fervid readiness to judge is the most detestable stupidity, the most pernicious evil. Not that the novelist utterly denies that moral judgment is legitimate, but that he refuses it a place in the novel. If you like, you can accuse Panurge of cowardice; accuse Emma Bovary, accuse Rastignac—that’s your business; the novelist has nothing to do with it. Creating the imaginary terrain where moral judgment is suspended was a move of enormous significance: only there could novelistic characters develop—that is, individuals conceived not as a function of some preexistent truth, as examples of good or evil, or as representations of objective laws in conflict, but as autonomous beings grounded in their own morality, in their own laws. Western society habitually presents itself as the society of the rights of man, but before a man could have rights, he had to constitute himself as an individual, to consider himself such and to be considered such; that could not happen without the long experience of the European arts and particularly of the art of the novel, which teaches the reader to be curious about others and to try to comprehend truths that differ from his own. In this sense E. M. Cioran is right to call European society “the society of the novel” and to speak of Europeans as “the children of the novel.””

MarkW

Jul 17 2023 at 1:36pm

Another nice Kundera piece can be found at Reason. In light of the feud with Havel, the idea that “Suspending moral judgment is not the immorality of the novel; it is its morality”, to some extent seems strongly related to the essence of the dispute (and something of a convenient belief for Kundera).

As for thinking of liberals as ‘children of the novel’, it seems that literary fiction may be going (or is well already on its way) to follow poetry and painting into declining cultural relevance. When was the last best-seller that was widely read, influential, praised by critics, and given a cinematic treatment? Atonement? No Country for Old Men? The eulogies for Kundera feel a little bit to me like eulogies for the novel’s important role in our modern culture)

Comments are closed.