Hofferth and Sandberg’s “How American Children Spend Their Time” (Journal of Marriage and the Family, 2001) doesn’t only estimate the effect of time usage on academic achievement. It also estimates how the way kids spend their days affects their behavior.

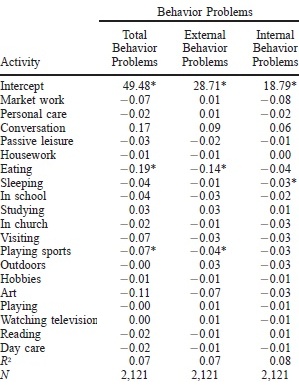

H&S have three measures of behavior problems. There’s a measure of total problems, plus subscales for external problems (acting badly) and internal problems (feeling badly). Higher scores indicate more problems; SDs are 8 for total problems, 5.4 for external problems, and 3.2 for internal problems. Results continue to control for child’s age, gender, race, ethnicity, head of household’s education and age, plus family structure, family employment, family income, and family size.

Results for behavior problems are even scarcer than for academic achievement. None of the nineteen kinds of time use predict behavior problems across the board. Only two – eating and playing sports – have statistically significant effects on total problems. How big are the effects? Ten extra weekly hours of eating time cut problems by .24 SDs. Ten extra weekly hours of sports cut total problems by .09 SDs.

Look at all the stuff that doesn’t matter: school time, study time, reading time, church time. Furthermore, contrary to pro-play psychologist Peter Gray, play time has near-zero effect on either external or internal behavior problems. Play may be intrinsically valuable for kids. I argue precisely this in The Case Against Education. But at least in this data set, the instrumental benefits of play are invisible.

While reverse causation remains a possibility, Hofferth and Sandberg do control for most of the obvious confounds. The large effect of eating time is at least consistent with preaching about the importance of shared family meals, though more plausibly long meals are a symptom of general family togetherness. Furthermore, even if we treat the effect of sports as entirely causal, it’s still miniscule – especially compared to the triumphal rhetoric of our national cult of sport.

The chief takeaway, though, is that adults – not just parents but educators – need to relax. At least within the observed range, setting kids’ daily agendas is almost fruitless. It’s not helpful, it’s not harmful, it’s just bossy.

HT: Sandra Hofferth for giving me the mean and SD of the behavior subscales.

READER COMMENTS

Eric Rall

May 18 2015 at 1:50am

Out of 19 activities, I’d expect about one of them to have a statistically significant effect at 95% confidence purely by chance, even if none of them actually had a causal link.

Andy

May 18 2015 at 10:58am

Rule of thumb for time use studies: Good when time is on the left hand side of the regression, but approach with extreme skepticism when time is on the right hand side.

The measures of time use in both the ATUS and PSID (and every other time diary dataset I’ve seen) are a) extremely noisy, b) imprecisely defined, and c) very likely to vary wildly based on the day the interviewer showed up. These factors combined lead to a very large attenuation bias when these measures are used as independent variables. The most remarkable things in this result and the previous one you discussed is that *any* measures were statistically significant. (Which in turn is less surprising when combined with Eric’s above point about random chance leading to significance).

Of course, the measures are still good as cross-sectional depictions of average behaviors and can be reliably put on the left-hand side where these measurement problems end up in the error term.

Brad

May 18 2015 at 2:07pm

Please don’t show this to my kids.

Willem

May 18 2015 at 4:18pm

Is the data out here? Because I would love plots, not (just) regressions. This data feels very non-linear in many aspects. They have very few interactions and one specfication (tobit).

Willem

May 21 2015 at 7:42am

To answer my own question:

data center at : http://simba.isr.umich.edu/VS/f.aspx

Comments are closed.