China’s economy has recently become a subject of widespread concern. The FT has an article with the following headline:

China’s consumers tighten belts even as prices fall

The term “even” caught my attention. Surely the FT editors don’t believe that falling prices would be expected to boost consumption? That would be an Econ101-level error. And yet, the article also contained this odd claim:

Weak price growth is not automatically encouraging people to spend.

“Theoretically low prices should increase purchasing power of consumers, but that hasn’t been the case,” said Louise Loo, lead economist at Oxford Economics. “We think the reason is because the deflationary mindset has been quite entrenched.” “I think this is the start of a pretty structural trend,” she added.

“People have become a lot more precautionary . . . They think a lot harder about how they want to spend an additional dollar of income.”

I have no idea what theory Louise Loo is referring to, as it’s one I’ve never seen. Indeed, this sounds a lot like reasoning from a price change.

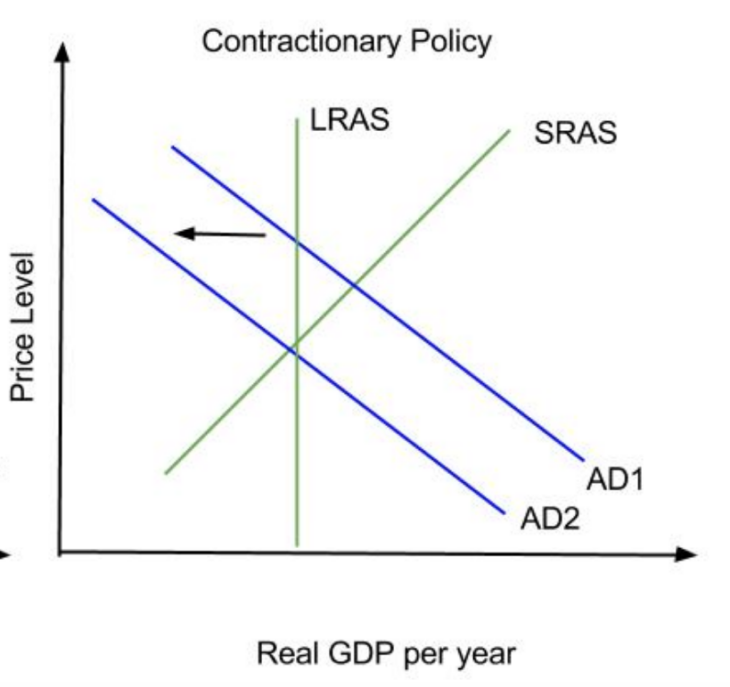

Here it might be useful to review the economy’s circular flow, which says that gross spending equals gross output equal gross income. Falling prices do not increase purchasing power, unless the fall in prices is caused by a rise in aggregate supply. But if the fall in prices was caused by a fall in aggregate demand, then you’d actually expect a fall in consumer purchasing power, as a decline in AD typically reduces real output and real income. Never reason from a price change.

In China’s case, the recent fall in prices is almost certainly due to a fall in AD (or more precisely a slowdown in the growth rate of AD). We know this because output growth is also fairly weak. This suggests that China’s monetary policy is too contractionary.

Milton Friedman once said that persistent inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. Here’s what I’d say:

Excessively tight monetary policy is always and everywhere misdiagnosed as some other problem.

This misdiagnosis occurs for several reasons. First, most people—even most economists—have no idea as to how to evaluate the stance of monetary policy. To put it bluntly, most economists wouldn’t recognize tight money if it were right in front of their nose. Second, most economies that suffer from tight money also suffer from other problems. Thus the falling prices and weak output are attributed to other aspects of the economy, not monetary policy. (Recall when the 2008-09 decline in AD was wrongly blamed on housing and banking problems.)

As an analogy, I recently had two consecutive illnesses. At first, I thought the second was my first illness getting worse. Only last Wednesday did I go to the doctor and discover I had diverticulitis (a condition I’d never even heard of.) I’ve also had colds that morphed into pneumonia. In those cases, I failed to initially see the problem, assuming it was just a “bad cold”.

This sort of error is excusable, as colds do actually make one more susceptible to pneumonia. Similarly, various “real problems” with an economy make it more likely that a central bank will adopt an excessively contractionary monetary policy. That’s partly because many central banks target interest rates, and real problems usually lower the natural or equilibrium rate of interest.

Mark Leonard recently interviewed a number of economists and other policy experts in China:

The critical question behind all this is how well the economy is actually doing. Among the Chinese economists I put this to, the most common answer was “very bad.” But they reject the Western analysis of peak China as a result of demographic issues, an absence of domestic reform and a negative international environment. Instead, they point to China’s structural advantages. Of its 1.4 billion citizens, only 400 million are middle and high income. The remaining billion are still low income — hundreds of millions of them in the countryside — and can still be brought into an urban industrial economy, boosting domestic demand as well as economic growth.

The key challenge for China is stimulating that demand. China has a lot of fiscal head room to do this.

At least they understand that the problem is aggregate demand, which the FT article doesn’t even discuss. But China needs monetary stimulus, not fiscal stimulus.

The Chinese economists understand that China has a lot of potential, if they can get the policy right:

The demographic situation is not the problem that Westerners think, they feel, at least in the short-term. China is not desperately short of workers: there is 20% unemployment for young people, and it is always possible to bring more workers in from the countryside. Economists are also positive about advances in new technologies. China is overtaking Japan as the world’s largest car exporter this year, and the Chinese company BYD is the world’s biggest manufacturer of electric vehicles, with sales that leave Tesla in the dust), and it is making progress in AI. Economists at Tsinghua and Peking University told me they have built models which show that China’s growth potential for the next decade is between 5 and 6% annually, through a combination of advanced industry upgrades and clean energy technology.

In short, Chinese experts feel the economic fundamentals are not as bad as Western debate suggests. Where they are really pessimistic is about the politics. “The United States can’t stop China’s growth,” one economist said, “only the stupidity of our leaders and the sycophancy of their advisers can do that.”

The entire article is excellent—well worth reading. It’s also one of the saddest articles that I’ve read in years.

HT: David Levey.

PS. The title and subtitle of Leonard’s article caught my eye:

Sunset of the Economists

Two decades ago, China’s reformist economists walked the halls of power and dictated policy. Now, they have been side-lined in favor of a new priority: national security. What happened?

Wouldn’t these headlines also be somewhat accurate:

Two decades ago, America’s reformist economists walked the halls of power and dictated policy. Now, they have been side-lined in favor of a new priority: national security. What happened?

Two decades ago, Russia’s reformist economists walked the halls of power and dictated policy. Now, they have been side-lined in favor of a new priority: national security. What happened?

Yes, what happened to the entire world?

PPS. Instead of an article with hundreds of ambiguous words, if only the FT had given us this graph:

READER COMMENTS

tpeach

Feb 12 2024 at 12:09am

Could the theory they have in mind be something like the Pigou (or real balances) effect?

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2024 at 7:56am

Yes, that might work in theory. But the Pigou effect is utterly insignificant unless the deflation is really extreme.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Feb 12 2024 at 7:01am

Except for a pretty brief period in the Clinton administration, reformers never walked the halls of power in the US and they failed to use the (temporary) fiscal surpluses to reform taxes structurally: taxation of net CO2 emissions, elimination of business taxes, VAT for wage taxation, progressive consumption taxes for income taxation.

Scott H

Feb 13 2024 at 7:25pm

Because they’re beholden to an electorate that absolutely doesn’t believe in those things — thank you education system.

Rajat

Feb 12 2024 at 7:11am

Stephen Kirchner has an excellent recent Substack post on China, in which he comments that “the managed exchange rate is a constraint on monetary policy”. More specifically, he suggested that “China toyed with a more flexible exchange rate in 2015, but walked that effort back very quickly at the first signs of exchange rate volatility.”

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2024 at 7:57am

Yes, that could be the problem.

Todd R Ramsey

Feb 12 2024 at 10:03am

Is the slowdown actually caused by many bad micro policies, rather than macro policy?

Leonard: “Xi thinks China succeeded because of Marxism-Leninism, and is doubling down on it.”

In this line of thinking, Deng’s reforms freed millions to deploy resources according to the particular circumstance of time and place. Growth ensued. Now Xi is constricting that freedom through policies like the (now ended) Covid lockdowns and jailing of entrepreneurs who are amassing resources outside of state control. By centralizing control, Xi is reducing the production possibilities frontier.

Does anyone have thoughts about this theory?

Scott Sumner

Feb 13 2024 at 11:10am

“Is the slowdown actually caused by many bad micro policies, rather than macro policy?”

I think both are major factors.

spencer

Feb 12 2024 at 11:48am

Low R-gDp is due to the Keynesian macro-economic persuasion that maintains a commercial bank is a financial intermediary. It’s a confusion of stock vs. flow.

spencer

Feb 12 2024 at 12:28pm

As Leonard Da Vinci explained:

“Before you make a general rule of this case, test it two or three times and observe whether the tests produce the same effects”.

Dr. Philip George hasn’t even yet attempted to construct his “corrected money supply”.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Feb 12 2024 at 1:20pm

Maybe he meant that consumers had come to expect that the monetary authority was setting too low a target, one that was likely to result in recession and that precautionary savings were in order?

Lizard Man

Feb 12 2024 at 11:28pm

What seems to have happened to the US is that its elites realized that China wasn’t going to liberalize its political system, its economy was going to keep on growing, its leadership would use military force to conquer Taiwan if they felt the odds were in favor of their victory, and that China’s military has something like a 50/50 chance of becoming capable of conquering Taiwan in the near future.

David S

Feb 13 2024 at 10:32am

It’s almost like Xi is an upside down version of Erdogan when it comes to an understanding of the economy. I can imagine him making this pronouncement:

“Prices will fall until everyone is wealthy!”

Although, he doesn’t seem to have much concern for wealth as long as people have sufficient nationalist enthusiasm.

Sorry about the diverticulitis. I recommend psylium—and not the crappy version that Metamucil sells–go for the whole husks with no fillers.

Scott H.

Feb 13 2024 at 7:43pm

My understanding of the Sumner monetary policy definition is that it defines a RESULT and not any particular set of actions.

With respect to achieving an expansionary monetary policy, the logical conceit is that it should be relatively straight forward for properly educated central bankers to devalue their own damn currency.

Jim Glass

Feb 13 2024 at 11:52pm

Isn’t that something? Nobody can stop China except its own stupid sycophantic Leninist regime. Nobody can stop America except its own idiotically self-riven democratic regime. Nobody can threaten the security of the Western Europeans except… There’s a lot of this going around these days.

Yes, but too bad about that regime they have….

This is Leninist economics 101. It’s why the Soviet Union put Gagarin in space in 1961 but didn’t have toilet paper until 1969. Xi’s learned the lessons of his heroes well and is doubling down on them throughout the Party and economy. Don’t expect it to change.

That said, “there’s a lot of ruin” in such a big economy. China and the world can be OK with this. I’m far more concerned about the ideologically aggressive Leninist doubling down of ‘stupidity and sycophancy’ that, unsurprisingly, simultaneously appears to taking place in its nuclear weapons policy. “This piece is incredibly candid considering it is coming from a Chinese commentator…”

Listening to that, monetary policy is maybe not my first concern.

Jim Glass

Feb 16 2024 at 10:17pm

David Rennie, Beijing bureau chief for the Economist, talks about a wide range of issues as seen from inside China today.

Comments are closed.