Part 1: Which Experts Matter in a Pandemic?

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we might have thought that “the experts” knew best and could guide us. But there is more than one area of expertise. And the speed, scale, and scope of this pandemic mean that we don’t know which areas of expertise matter or how to balance competing considerations coming from those that do. It would be a mistake to try to find one person to blame for what might turn out to be a case of expert failure. The root problem is not faulty expertise or bad actors. The root problem is that we are asking experts and politicians to do more than is humanly possible.

There is a structural problem with experts that is rooted in the division of labor that feeds us all. Each of us specializes in one or a few tasks. We make more than we want of some things, not enough of others. We make too much of a few things we may not even want, and too little of the things we do want. That’s okay, however, because we can trade our respective surpluses. Because we trade, each of us gets more of the many things we ultimately desire than we could have hoped to make on our own in splendid isolation. It is the system of specialization and trade. Each of us occupies a more or less unique place in this division of labor. But because we are specialized, each of us will know some things, but not others. We are, all of us, in our separate silos. The barber knows about hair clippers, but not teeth. The dentist knows about teeth, but not hair clippers. The flip side of the division of labor is the division of knowledge.

Because of this division of knowledge, each of us has expertise that few others have. In this sense, we can say that the division of labor is a division of expertise. And that’s what creates trouble at a moment such as this when we are driven to seek out the experts’ advice when taking collective action. The world’s governments today are turning to the experts. But to which experts? Which silos of expertise matter?

We are struggling with the tradeoff between stopping the virus and stopping the economy. Epidemiologists warn us to maintain social distancing. They want to put much of the economy on hold. But economists warn us of unemployment and cascading bankruptcies. Psychologists warn us that unemployment and isolation promote substance abuse and suicide. And so on. Who can adjudicate their competing frameworks?

Unfortunately, no one can be a grand meta-expert rising above the many lesser experts. The meta-expert would have to know everything, in which case we would not have a division of knowledge at all. Every expert is a lesser expert with prefabricated problems and solutions that define their expertise and apply only to one thin slice of reality. Their disciplinary expertise makes certain problems relevant and prescribes certain solutions to those problems, and only those problems. But this means that when politicians take the collective action recommended by their experts, somebody else is deciding for us “what is and is not relevant to us.” And those prefabricated “relevancies” will reflect some areas of expertise and not others, some slices of reality and not others.

If the politicians listen only to the epidemiologists, then one set of relevancies matters, and the rest will be ignored. Just as the barber will recommend a haircut and ignore the toothache, the epidemiologist will recommend lockdown without considering what unemployment and idle resources may imply for our overall physical and psychological health. Does that mean that the politicians should consult both epidemiologists and economists? Perhaps. But how will they decide which set of prefabricated interpretations to apply where and how? How are they to balance the competing considerations coming from the experts’ separate silos? And how many such silos are they to balance? Shall they consider only epidemiologists and economists? What about psychologists? Sociologists? Ecologists? Anthropologists? Engineers?

We cannot avoid this impossible balancing act once we are in collective decision-making mode. Inevitably, the experts upon whom we rely are lodged firmly in their several silos. And there is no agreed-upon, rational, and proven technique for striking some sort of equilibrium among them. We’re flying blind. “The pandemic will pass,” Nobel economist Vernon Smith has wisely admonished us. And once it has, we should seek out ways to avoid the necessity of balancing competing areas of expertise. It is a fundamentally impossible task that requires arbitrary actions that are correspondingly impossible to justify to the satisfaction of all reasonable persons. Let’s try to avoid that in the future if we can.

Roger Koppl is Professor of Finance in the Whitman School of Management of Syracuse University and Associate Director of Whitman’s Institute for an Entrepreneurial Society (IES).

READER COMMENTS

Mark Brady

Mar 30 2020 at 4:59pm

And would you agree that the “experts” in one area of “expertise” don’t agree with each other?

See, for example, the perspective of Dr. Sucharit Bhakdi, Professor Emeritus of Medical Microbiology in Mainz, Germany, who wrote to Angela Merkel, calling for an urgent reassessment of the response to Covid-19 and asking her five crucial questions. You can find the text of his open letter and a great deal more here:

https://swprs.org/a-swiss-doctor-on-covid-19/#latest

MrLibertyFighter

Apr 1 2020 at 2:11pm

Oh man, thank you so much for this link, this is a massive treasure trove! I’ve been following Bhakdi for the last couple of weeks, as well as Dr. Wolfgang Wodarg, who basically says the same thing as Bhakdi.

Alan Goldhammer

Mar 30 2020 at 5:01pm

Along with other blog posts here, this one misses the trees in the forest. Those of us who come from a health science background know exactly what has gone wrong and why we are at this state. Had nothing been done, the economy would have suffered though increased fatalities, lost work time from a very large number of workers over a prolonged period of time, and a virtual shut down of hospital systems because of critical pneumonia brought about by SARS-CoV-2 (this latter problem may still affect some particularly hard hit areas). There is enough epidemiology to predict how much the economy would suffer if nothing had been done (this was initially the approach the UK was going to take until the projected health impact came from the Imperial College group).

As far as I can tell, no nation is willing to become the control or “do nothing” group in this clinical trial. None of what is happening falls into the ‘rocket science’ category. Those of us who have worked in this area over the years are surprised only by the ineptness of the early steps when there was an opportunity to put in place a smaller ‘social distancing’ plan.

I hope Part 2 is more informative and constructive in terms of solutions.

Mark Z

Mar 30 2020 at 8:00pm

I don’t think it does, and I think the general point is pretty solid; a better critique would be that Koppl, being an economist, comes across as a bit more reticent to caution against, say, only listening to the economists, than against only listening to the epidemiologists.

My interpretation of the point is: each expert approaches public policy with his own target variable, largely to the exclusion of others. The epidemiologist is eyeing infection and mortality rates and coming up with policy recommendations to minimize those, but ignoring economic costs; the economist is eyeing GDP and coming up with policy recommendations to maximize that, while ignoring infection rates; the psychologist is eyeing suicide and depression rates, and trying to minimize those. I don’t see Koppl criticizing epidemiologists for failing at their own profession, e.g., understanding the outbreak or even challenging their understanding of how to minimize their target. Rather, it’s that they the expertise is within the context of their field doesn’t help them (or economists, or psychologists) know what the appropriate weight is to give each field’s primary targets.

The interaction between fields also obscures experts’ comprehension of the ultimate consequences even of the things they understand directly. For example, an epidemiologist may understand that shutting down nonessential production or quarantining a highly infected area is good epidemiological policy; but he may not grasp that the social and economic fallout have epidemiological consequences of their own: perhaps the the shutdown leads to expected shortages and mass panic shopping, leading to an increase in the virus’s spread; or the local quarantine causes people in the afflicted area to flee before it takes effect, exacerbating the spread to other areas. Or an economist may see a lockdown as bad for production levels without appreciating that the epidemiological consequences of ordinary economic activity may lead to recurrent future outbreaks that will reduce output by a greater amount in the longer run.

Jon Murphy

Mar 30 2020 at 10:04pm

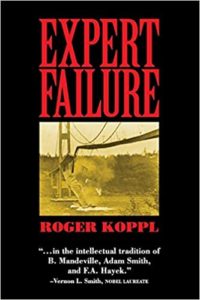

Right Mark. “Expert Failure” here should be read in the same way as “market failure,” which is a failure of the experts to adequately take into account all relevancies. It doesn’t imply any incompetence on the part of the experts.

Thaomas

Apr 2 2020 at 8:42am

“Economist is eyeing GDP and coming up with policy recommendations to maximize that, while ignoring infection rates”

I don’t think you can find many economists’ models that maximize GDP in ignorance of the public health effects of alternative polices.

robc

Mar 31 2020 at 10:04am

Sweden is the control group.

robc

Mar 31 2020 at 2:42pm

also Iceland and Belarus.

Phil H

Mar 31 2020 at 2:40am

The US has twice as many people infected as China. As many people have died. And economists are still calling for “balance” between infections and the economy. What this means is that those US economists making this call value American lives lower than the Chinese government values Chinese lives.

That’s a really bad look.

(I’m always cautious about Chinese statistics, but I don’t see any sign that the covid death figures have been manipulated.)

Mark Z

Mar 31 2020 at 3:18am

Newsweek and Bloomberg are reporting that the number of cremations occurring recently in Wuhan is much much higher than the reported death rate (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-27/stacks-of-urns-in-wuhan-prompt-new-questions-of-virus-s-toll). There may be other explanations, but I think it’s a real enough possibility that China is concealing a considerable number of cases and deaths. In fact, I find it pretty much incredible (not in the sense of ‘really’ though it is really good if true, but in the sense that I don’t believe it) that they’ve completely stopped new infections in Wuhan, as is now being claimed. I think comparisons with China should perhaps come with asterisk for the time being.

Phil H

Mar 31 2020 at 5:06am

Yeah, that’s definitely fair. That said, I’ve been waiting for the other shoe to drop for a while. I have no insight into what’s going on in Wuhan (many miles away), but elsewhere in China, we can drive up to and look at the hospitals, and the WeChat grapevine is still working its magic. In my town, there is not yet a second-wave outbreak, and I haven’t heard of any in other towns, either.

So, provisionally, I’m believing what I see. We sometimes talk about bets and skin in the game on this blog: my children’s skin is in the game. Last week I was very worried about second wave transmission, and I literally kept them inside 24*7. This week, I am relaxing a little, and have let them out to play.

Jon Murphy

Mar 31 2020 at 7:15am

That assumes no relationship between economic activity and medical care, a highly dubious assumption.

Phil H

Mar 31 2020 at 8:19am

No, I really don’t. I assume that the virus can be stopped – and that assumption might be wrong. My assumptions are that the Chinese model has worked: by hitting the brakes hard on economic and social activity, for one quarter they (we!) have broken the chain of transmission. They are now free to resume economic activity, with a test and trace program to prevent further outbreaks.

One quarter of extremely depressed economic activity is not going to harm the ability of China or America’s hospitals to deliver healthcare. And if no more people in China die, that’s a lot of human value saved. Beating the virus is the big win.

If I’m wrong about the effectiveness of the Chinese strategy, then my argument falls down.

Jon Murphy

Mar 31 2020 at 8:48am

The assumption is implicit; I don’t think you realize you’re making it, which is why I called it out.

An economy is not about money or profit/loss. It’s an organic system that coordinates human activity and helps achieve collective and individual goals. By arguing that the Chinese shutting down their economy to prevent the transmission of the virus versus President Trump’s (but not the states’) unwillingness to do the same means that the Chinese value human lives higher than Americans necessarily implies no connection between economic activity and health care. Now, obviously that is false. Plus, there’s tentative evidence coming out of Sweden and Korea, both of whom avoided draconian shutdowns, that indicate the shutdowns may actually cost lives (it should be stressed this evidence is tentative).

Part of Koppl’s point is that these tradeoffs exist, that shutting down the economy costs real lives and can hinder medical recovery. This is something many people don’t understand (indeed, we often see similar denial of tradeoffs in climate change discussions).

Phil H

Mar 31 2020 at 9:11am

“Part of Koppl’s point is that these tradeoffs exist”

I know. He’s wrong.

As I explained above: “One quarter of extremely depressed economic activity is not going to harm the ability of China or America’s hospitals to deliver healthcare.”

Over the long term, of course economic activity and healthcare will be related. My argument is that they are not related in the short term. And this crisis could be resolved in the short term. Not resolving it is a choice.

Jon Murphy

Mar 31 2020 at 9:58am

No, it’s a fact of life that tradeoffs exist. Goods and services are indeed scarce. For every resource devoted to making masks, for example, there are fewer resources to making respirators.

Ironically, your comment is a brilliant demonstration of Koppl’s point of expert failure.

Jon Murphy

Mar 31 2020 at 10:04am

If you truly believe trade-offs do not exist, the explain the following:

-Why, based on the logic of shutting things down and “flattening the curve,” Milan ordered their subway hours cut, only to rescind that order when it was discovered such efforts facilitated the transmission of the disease?

-Why, based on the logic of shutting things down and “flattening the curve,” the governor of Pennsylvania ordered rest stops along the highway closed, only to rescind that order when it was discovered such efforts hindered the transportation industry’s ability to get goods (food, medical supplies, toilet paper, etc) where they are needed?

-Why, based on the logic of shutting things down and “flattening the curve,” did the same governor order all “non-essential” companies shut down, only to reopen some of them when it turns out those “non-essential” companies actually make essential (or parts of essential) equipment?

–Why there are exceptions at all to stay-at-home orders?

Phil H

Mar 31 2020 at 10:05pm

Because people have to eat.

Wow, writing it in bold really does make me seem smarter.

Jon, can you not see how your argument has changed? Koppl referred to a balancing act between economists and epidemiologists. I.e. economy vs. healthcare. You have changed the terms of the argument to which services are necessary as part of the healthcare supply chain. They do indeed include unexpected things like truck rest stops.

Understanding that healthcare is complex is different from balancing healthcare against the economy.

Roger Koppl

Apr 1 2020 at 9:36am

FWIW, Phil H, Jon Murphy is interpreting me correctly and I don’t think that he was in any changing his position. I tried to carefully avoid taking a policy stand, so shame on me if I allowed readers to think I was somehow pushing for jobs against death or something like that. It’s just that, as Jon seems to be saying, “the economy,” too, is a matter of life and death. The trouble is that we don’t know how to somehow balance, or perhaps I should have said integrate, the different areas of expertise. And the why of it has very much to do with complexity, as Jon notes.

Jon Murphy

Apr 2 2020 at 10:59am

Thanks, Roger. That’s a more elegant way of stating what I was going for.

Thaomas

Mar 31 2020 at 8:46am

“And once it has, we should seek out ways to avoid the necessity of balancing competing areas of expertise.”

And if there were a way to do this, why wait? Why shouldn’t “we” have done so already.

In a way the lesson is exactly the opposite. We should seek ways for experts to incorporate some of the balancing or at least recognize the need for balancing competing objectives in their recommendations.

Tom DeMeo

Mar 31 2020 at 1:01pm

Unfortunately, no one can be a grand meta-expert rising above the many lesser experts. The meta-expert would have to know everything…

Wrong.

How ridiculous this post is. Do you drive a car? Use a computer, or a mobile phone? Well, I can pretty much guarantee you that any of the CEO’s of the companies that manufactured those products knew considerably less than 1% of the technical knowledge required to build those products. And yet, magically, these products exist and are ubiquitous.

The ability of human beings to create complex hierarchies and do difficult things beyond any one person’s capacity may be imperfect, but it is also self-evident.

The meta-expert has to determine what meta-data they will need that will inform their larger decisions and where to find it, nothing more. The “experts” would be responsible and accountable for providing accurate meta-data in their field of expertise. Where we get into trouble is when we ask an “expert” to make decisions that require information and judgement outside of their expertise.

That isn’t expert failure, that’s leadership failure

Peter Prior

Apr 21 2020 at 3:11am

Tom, you are spot on correct. I think you could describe the weighting of expert advice in decision making as common sense. The politicians have been too strong on taking expert advice and weak on weighting it correctly. It was obvious to me before the impositions of lock downs, that it was the common sense civic duty of that part of our population that was especially vulnerable to the the impact of this disease, ( including me) to keep the hell out of its way, if they possibly could, until the less vulnerable part of society had developed some herd immunity or a vaccine had been developed or better treatments for the disease had been found. This could have included the government providing for grandparents, living with extended families, separate accommodation, until the first peak of the epidemic had passed. Its common sense to keep the vulnerable as well as possible, rather than treat them expensively in hospital when they get sick. Require social distancing, reduced capacity of public transport and an interruption to social events, but not a substantial close down of commerce.

A well educated, free thinking, society would instinctively have understood this, but our education system does not encourage people to think for themselves. It encourages people to effectively tick the box which the currently fashionable expert thinks is the correct box. And it encourages people to believe what experts say without questioning it. In my experience, experts are often wrong and they are mainly motivated by patronage.

Joseph E Munson

Mar 31 2020 at 8:23pm

I mean I think this can be solved by using economic estimations of the value of a life, and than balancing that with the death estimates of not social distancing by epidemiologists (minus the deaths caused by the worse economy).

Balancing the expert opinion of different subject matter experts does not like an impossible task at all to me.

Experts conferencing with one another can rapidly create “meta experts”, expert opinion is imperfect, but seems like the best tool we have.

Mark Bahner

Mar 31 2020 at 10:02pm

Don’t listen to epidemiologists. 😉 Listen to engineers. 🙂 Especially this engineer. 🙂

Think of what the ultimate in social distancing would be. What would it be? It would be everyone walking around in space suits. There would be no way for viruses to get in or out. You could stand 1 foot from someone, you could hug them, you could even touch space helmets and breath on the inside of your visor, and there would be no viral transmission.

Rather than the “social distance” that the epidemiologists want, we should simply all be wearing filter masks and gloves. (But no hugging, unless we switch to space suits.)

Mark Bahner

Mar 31 2020 at 10:06pm

Oops, I missed the reference to engineers. Yes, listen to engineers!

Matthias Görgens

Mar 31 2020 at 10:46pm

You can simplify the problem slightly.

If you can come up with a goal that you can objectively measure performance against after the fact, you can use prediction markets to guide you actions.

The goal doesn’t have to be perfect nor perfectly measured. Eg you could try to minimise quality adjusted life years lost. And make sure your quality adjustments take unemployment into account.

Agreeing on that goal mean agreeing on the ratios of tradeoffs. Not easy, but still a smaller task than agreeing on all policy actions.

Thaomas

Apr 2 2020 at 8:49am

Comments are closed.