By John P. Mackey and Walter E. Block

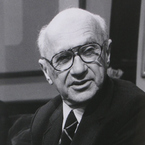

In his September 18, 2020 New York Times column, Binyamin Appelbaum appeared to be highly critical of Milton Friedman.

The former started out by calling the latter “a free-market ideologue,” and he did not mean this as a compliment. He ended on this note: “After 50 years of listening to Friedman, it’s time to do something about the flaws (in the views of this Nobel Prize winning economist).” In between, he maintained we should no longer wait for, or rely on, businessmen to renounce “selfishness portrayed as a principled stand,” as he purported Friedman would have it. It is now time- it is past time, in his view, to get the government involved in compelling the wealthy in effect to support social justice.

It would appear at the outset to be a 180 degree difference between these two writers. Not so, not so, at least not when it comes to goals. Both seek an end to poverty, favor prosperity, freedom and economic development. Appelbaum supports egalitarianism, Friedman did not, but even here it is possible to at least partially reconcile their differences. The journalist favors heavy taxation of the rich and financial support for the poor; the economist would go part way in that direction with his negative income tax (those at the bottom end of the income distribution pay a negative tax; e.g., receive a subsidy). Moreover, Friedman would attest that economic growth disproportionately helps the impoverished. 200 years ago, 94% of everyone alive on Planet Earth lived on less than $2.00 per day. Today it is only 10%. The average lifespan in 1820 was 30, today it is 72.6 (which is higher than in any country in 1950). In 1820, illiteracy rates were 88%, while today they have shrunk to only 14%.

No, the gigantic, stupendous, difference between the two scholars concerns means, not ends. And here we side completely with the University of Chicago professor who was the most prominent dismal scientist of the 20th century (many scholars would argue that Keynes was), and should continue that position in the present one.

What are the specifics?

Appelbaum wants to leave off “the public shaming of restaurants that refuse to give paid leave to sick employees” and have a law enacted compelling them to do just that. But what determines employee well-being is total wages, the monetary plus the non-monetary (health care, safety on the job, and other fringe benefits). The firm cares not one whit about the proportions; its eye is only on the cost of the total compensation package. It has every incentive to allocate remuneration in accord with worker preferences. Mr. Appelbaum does not realize that if paid family leave is given, and total compensation (based on productivity) does not change, then something else will be reduced, presumably take home pay. Most workers would rather have higher take home pay than paid family leave if this means to an agreed-upon end is implemented. This is basic economics 101, and there are few people who have contributed more to it than Milton Friedman.

Similarly, the New York Times editorialist avers: “Instead of pleading with McDonald’s to raise wages, raise the federal minimum wage.” But as Professor Friedman would explain, this legislative enactment does not raise compensation, certainly not in the long run; rather, it serves as a barrier over which an employee’s productivity must rise, if he is to obtain and keep a job. When compensation is legislatively raised above what the labor productivity of the low-skilled worker is contributing, the firm will either be forced to make an investment in new technology and/or take on more highly skilled employees, so as to substitute for the displaced workers. Keep raising it, and more and more less-skilled workers will be legislatively consigned to permanent unemployment. Again, neither man wants that. They disagree on means, not ends.

Also on Applebaum’s wish list is that our society “combat discrimination … reduce pollution (and) maintain community institutions.” Friedman was certainly a world class economist, and his legacy also includes many of his students. Gary Becker, Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams would be the first to reply to Appelbaum that different wage levels, whether between whites and blacks or men and women, do not necessarily indicate discrimination. Friedman would have no problem with a law reducing pollution (he supported his colleague Ronald Coase’s solution in this regard), but he would insist that if any one firm carried out this policy, it would court bankruptcy. He also had no problem with supporting charitable organizations; he only insisted that people do this with their own money, not that of others (such as CEOs on behalf of stockholders).

States Mr. Appelbaum: “Friedman’s negative vision of government has helped to obscure the ways the public sector can help the private sector, for example by investing in education, infrastructure and research.” But a careful perusal of his famous book, Capitalism and Freedom will demonstrate that Friedman’s concept of “neighborhood effects” supported precisely these three policies. He saw a market failure in what most economists would call positive externalities: we all benefit from the education of others, infrastructure that we need not use directly and general research. Therefore, the government should subsidize these efforts, lest resources be misallocated.

One last example. The editorialist wants “to convince banks to steal less money from customers.” This is presumably a misprint. Obviously, he wants savings institutions to engage in no robbery at all. Does anyone doubt that the economist would enthusiastically support this?

There are deep dark chasms between Freidman and Appelbaum concerning means to an end, but less so, far less so, regarding goals they both share.

John P. Mackey is Co-Founder and CEO of Whole Foods Market

Walter E. Block is Harold E. Wirth Eminent Scholar Endowed Chair and Professor of Economics at Loyola University New Orleans

READER COMMENTS

Alan Goldhammer

Oct 25 2020 at 10:48am

It would have meant more to me had the co-authors compared what Applebaum said in his book, ‘The Economists’ Hour’ as that goes into the argument in far more detail than the column in the Times.

Jon Murphy

Oct 25 2020 at 11:09am

How does what he writes in the book rebut what Block and Mackey write here?

Alan Goldhammer

Oct 25 2020 at 1:43pm

I guess you will just have to read the book. As I recall, there was a whole chapter on Friedman and it was not entirely critical.

Jon Murphy

Oct 25 2020 at 1:58pm

What will reading the book tell me that their NYT article didn’t? Did Applebaum fail to properly summarize his argument in his article?

David Henderson

Oct 25 2020 at 10:58am

Nicely done, John and Walter. And Walter, what a coup getting Mackey to co-author with you.

Anders

Oct 26 2020 at 10:31am

First of all, to my mind, the main contribution of Friedman has been to bring economic thinking into the public realm – quite a feat for anyone who has tried to explain to an incredulous audience why people working in their self-interest helps all on the aggregate and in the long term (as long as there is competition).

Second, what strikes me is this thought experiment: imagine we would shut Friedman together with a leading adversary, such as Chomsky, into a room and not let them out until they have agreed on a set of basic suggestions. What would they come up with?

Based on my readings of both, SEVERAL things come to mind:

Some kind of universal basic income, replacing the entire welfare system;

Decoupling education funding from land taxes (in the US) and allowing for competition among schools, whether private or public, with government guarantees that education will be funded;

A system where government finances higher education and recoups the investment through subsequent higher taxes on income, removing the risk of unsustainable debt by tying repayment to wages, radically cutting the need for federal investment into higher education, and making higher education accessible and affordable to anyone who qualifies;

A system of federal backstop financing of high-cost health care, such as exceeding 20% of annual income (less for those making under, say, 80 k) – leaving about 80% of health care spending to operate under relatively free market conditions and empowering consumers to shop around (the gall bladder operation that is listed at over 20 k at the Mayo clinic can be had for 10% of that amount in several places).

None would come out fully satisfied, but much more satisfied than with the current situation where not only public spending is high – Americans also do not get much bang for their public buck.

Just a thought.

Monte

Oct 27 2020 at 4:23pm

Steven Pinker (Noam Chomsky colleague) has said that Chomsky “portrays people who disagree with him as stupid or evil, using withering scorn in his rhetoric.” So any suggestion that the two, in person, would arrive at some consensus regarding public policy puts me in mind of the first two lines of Kipling’s famous poem, “The Ballad of East and West.” I suspect it would more closely resemble Biden-Trump Debate I.

Hanoch

Oct 27 2020 at 6:51pm

I am not entirely convinced about this. I don’t know much about Applebaum, but if he is anything like your typical leftist, he would likely gladly consent to a reduction in “prosperity, freedom and economic development” if it furthered the much-sought egalitarian Utopia.

Comments are closed.