Arnold Kling replied to me recent post discussing a 4% inflation target (a policy I oppose, by the way.) I strongly disagree with all 6 of his points. He is responding to this claim I made:

The simplest solution is to commit to buy T-bonds (and, if needed, Treasury-backed MBSs) until TIPS spreads show 4% expected inflation. At that high an inflation rate you don’t need much QE, because the public and banks don’t want to hold much base money.

Arnold responds:

1. Central banks have tried many times to commit to pegging exchange rates, which in principle seems easier to do than pegging an inflation rate. These attempts have often failed, as the central bank finds itself overwhelmed by private speculators. This suggests to me that one should be skeptical of the effectiveness of open-mouth operations.

I know of no examples where a central bank tried to prevent a currency from appreciating and had to give up the peg due to the actions of private speculators. (And no, the recent Swiss case was certainly not one of those examples. Denmark held on, and the Swiss could have also done so.) As far as I know the cases where currency pegs are overcome by speculators are those where a country is trying to prevent depreciation. Those cases have no implications for the claim that the Fed can raise inflation to 4%.

2. Suppose that the Fed backed up its commitment to 4 percent inflation with a lot of action. My belief is that it would take a great deal of action-an order of magnitude more than what we have seen.

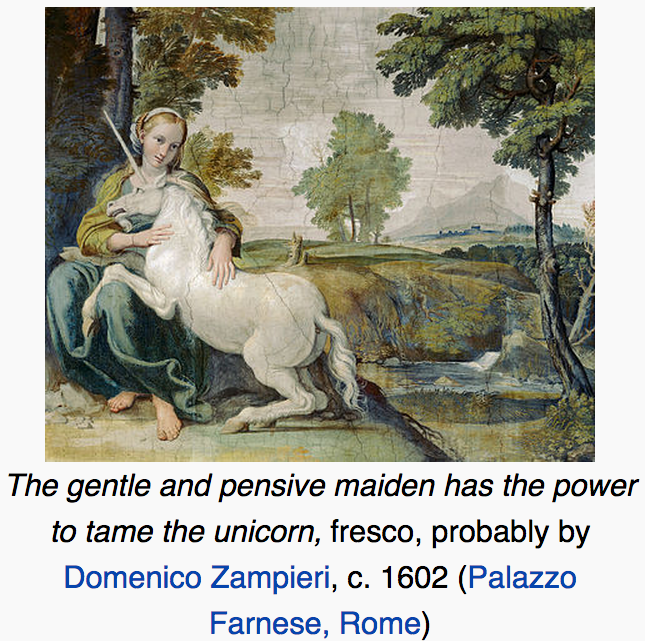

In fact, no action would be needed, as the demand for base money at 4% TIPS spreads (i.e. 4% expected inflation) and zero interest on reserves, is almost certainly far lower than the current stock of base money. The Fed could raise the inflation target and do “negative action”, reducing the base. In all of human history I know of no example where there is 4% expected inflation and a substantial demand fore non-interest bearing base money. Arnold’s claim is sort of like, “assume a unicorn”. He’s postulating a 4% expected inflation rate and a high demand for base money. How is that even possible?

And even if it did take an order of magnitude more action—so what? I can’t think of any outcome better than foreigners financing America’s entire national debt at 0% interest at a time of 4% inflation. Sweet!!

3. By the time inflation reached its 4 percent target, there would be a great deal of “inflation consciousness” among investors and in the general public. We would get into a regime of high and variable inflation. You do not know whether inflation would tend toward 4 percent, 8 percent, or 12 percent.

The Fed implicitly targeted inflation at roughly 4% from 1982 to 1989, and these problems did not arise. By targeting the TIPS spreads we’d let the market direct monetary policy, not the Fed. I’d expect the outcome to be even better than during the Volcker years. If we’ve learned anything about monetary policy in recent decades, it’s that central banks using the Taylor Principle can easily keep inflation close to target, except at the zero bound. (And even then it hasn’t been all that far below 2%)

4. In this regime of high and variable inflation, prices would lose some of their informational value, as people find it harder to sort out relative price changes from general inflation. This would be detrimental to economic activity. Scott and I both remember the 1970s, and from a macroeconomic perspective, they were not pretty.

The 1970s were ugly precisely because we were not targeting inflation (or NGDP). A 4% inflation target would look nothing like the 1970s; it would be similar to the Volcker years (after 1982).

5. So fairly soon, you would see a reversal of policy, with Scott complaining about the stupidity of the Fed overshooting its inflation target. The Fed would take dramatic action to undo what it did before.

Again, inflation would stay close to 4%, so this problem would not occur.

6. After several painful years, we would be back to the regime of low and stable inflation.

A policy of 4% inflation is a relatively low inflation policy. So there’s nothing to go back to.

Again, I don’t support a 4% inflation target; it’s not a sensible policy. But it’s one of the easiest policies for any central bank to undertake, even easier than a 2% inflation target (as there is no zero bound problem.) It’s not optimal because NGDP targeting is better, but it is certainly feasible, indeed it’s hard to think of any macro aggregate targeting policy that is more feasible.

In much the same way, a gentle and persuasive central bank can convince base money holders to disgouge their hoards of cash through 4% expected inflation.

HT: TravisV

READER COMMENTS

Njnnja

Oct 19 2015 at 2:02pm

As far as I know the cases where currency pegs are overcome by speculators are those where a country is trying to prevent depreciation. Those cases have no implications for the claim that the Fed can raise inflation to 4%.

Maybe the fact that central banks have power in one direction but not the other is what people don’t get. We know that central banks can fail (spectacularly) when trying to defend against currency depreciation because it can run out of currency reserves. But obviously it can never run out of its own currency to defend against a currency appreciation.

Does inflation work the same way? A central bank can put as much currency into circulation as it wants by buying assets (QE style). Therefore, a central bank can hit its inflation target regardless of whether or not speculators show up with tons of transactions because the central bank can fill them *all* if it has to. But thinking about the opposite case, where the central bank wants to decrease inflation, is commensurate with trying to defend against a currency depreciation. They act as a demand for their own currency by supplying other assets in exchange, but just as the central bank can run out of foreign currency reserves to sell, they could run out of assets to sell and therefore end up with inflation that is higher than they want it to be.

For example, if the Fed says tomorrow that it wants to hit a deflation target by selling its securities at a 20% yield (and thereby suck out a ton of currency), every investor and their brother is going to try to take them up on the offer. And just as speculators can break a currency by selling currency at the too strong rate, speculators could “break” the deflation peg by actually showing up and demanding all those 20% yielding bonds. When the central bank can’t meet the number of transactions that are demanded of it, it will not be sucking as much currency out of the system as it wanted to.

This actually is kind of comforting because the idea of an omnipotent central bank does not sit well with many people. And the difficulty of keeping inflation sufficiently low because of, say, an unsustainable level of asset (gold) outflows, seems to fit with historical experience too.

But it also depends on people believing that hiking rates to 20% would not be inflationary, and since we can’t even get agreement on that I think the nuance of asymmetrical central bank power might be a bridge too far.

(I guess technically the limiting case is that the central bank can only buy all of the foreign assets in the world to prevent appreciation of its currency, which is similar to a central bank “limited” to buying all domestic assets in order to reach an inflation target. But that reductio ad absurdium kind of proves the point that inflation is always possible)

Kevin Erdmann

Oct 19 2015 at 2:06pm

Scott, couldn’t the Fed get part of the way toward your proposal by keeping their inflation target, but using your forward market mechanism to manage it? Couldn’t they buy and sell 5 year TIPS to peg breakeven inflation at 2%?

Glenn

Oct 19 2015 at 3:42pm

Njnnja,

With respect, I think it may be you that has missed the point, rather than Scott’s critics. In either direction, the Fed is constrained by the requirement that it be able to find willing partners to its transactions. The Board cannot force a third party to sell it non-cash assets at a price it is willing/able to pay any more than it could force a third party to buy its foreign cash reserves at a price it is wiling/able to offer.

The collapse in exchange rate pegs isn’t precipitated by central banks running out of foreign money; it is precipitated by central banks running out of willing buyers at prices it is willing/able to offer.

Similarly, there is no guarantee that a central bank could command prices for its newly printed cash at a level consistent with 4% inflation. It is likely that the public would be wary of this new regime, and respond accordingly. Consider taking it to its logical extreme, and suppose (as you said) the Fed intends to buy every non-dollar asset in the world, and pay for them in newly printed dollars.

You suppose the Fed could achieve this goal, because these assets can today be priced in dollars, and the central bank could reasonably be expected to print the dollars required to satisfy its demand.

Do you really think this wouldn’t change in response to the new fed policy?

No – as Arnold says, this is a policy prescription fraught with peril. No one knows what kind of policy action would be required to achieve 4% inflation (especially when the market wants a quarter that, despite good central bank intention otherwise). Any action would require the cooperation of a willing buyer on the other side, eager to trade interest-bearing assets with (the Fed hopes) rapidly depreciating currency. I suspect the Fed

Central bankers are not gods, but men. If there were easy solutions to the problems facing the US economy and its monetary policy guides today, they would have taken them. Be wary anyone who tells you dollars are just lying on the kitchen floor.

Kevin I

Oct 19 2015 at 4:44pm

Glenn,

Your comment is totally removed from not only basic economic theory, but from reality itself.

You describe a scenario where asset holders acknowledge the Fed’s commitment to its inflation target by raising prices today. Thus far, all is working as it should.

“The collapse in exchange rate pegs isn’t precipitated by central banks running out of foreign money; it is precipitated by central banks running out of willing buyers at prices it is willing/able to offer.”

This is called inflation. The same amount of dollars cannot buy the same amount of goods. If the Fed is satisfied with this level of inflation, it can stop buying bonds.

However, you seem to imply that the presence of a committed inflation target means the market will at some point declare the dollar worthless and refuse to sell the Fed assets for any price? Where does this massive and unexpected inflation come from? As long as the Fed is clear and honest about its target, the market has nothing to gain by overvaluing assets. If Janet Yellen handed me a $10 and I tried the buy a sandwich, do you think the store owner would look at me suspiciously and refuse to sell at any price, knowing the money came from the Fed?

“No one knows what kind of policy action would be required to achieve 4% inflation (especially when the market wants a quarter that, despite good central bank intention otherwise). ”

What does it mean for a market to “want” a certain level of inflation? How do you justify removing the price of money from its supply and demand?

CMA

Oct 19 2015 at 6:35pm

“As far as I know the cases where currency pegs are overcome by speculators are those where a country is trying to prevent depreciation.”

Are you saying the central bank can run out of ammo?

TravisV

Oct 19 2015 at 6:59pm

I wonder if Arnold Kling, Bob Murphy or any other big names will attempt a rebuttal to this…..

Scott Sumner

Oct 19 2015 at 7:59pm

Njnnja, Good points.

Kevin, You don’t want them directly trying to impact TIPS prices, by buying TIPS, as that might distort the risk premium. The goal is to indirectly impact TIPS spreads by adjusting the quantity of money.

Glenn, You said:

“No one knows what kind of policy action would be required to achieve 4% inflation (especially when the market wants a quarter that, despite good central bank intention otherwise).”

There are several problems with your comment. You seem to suggest that the Fed wants 4% inflation but can’t seem to get it. In fact, they don’t want 4% inflation. Nor does the market want 1% inflation, rather they expect 1% inflation (or 1.5%).

And we do know the kind of action that central banks would have to do to achieve 4% inflation, as the Volcker and Greenspan Fed did those actions during 1982-90, and could have done them for much longer if they had chosen to. Instead they opted for 2% inflation.

Central banks buy assets at current market prices, in order to adjust the size of the monetary base. We know from experience that at 4% inflation the central bank only has to buy a very small quantity of assets, presumably Treasury bonds, purchased at the going market price.

You said:

“Central bankers are not gods, but men. If there were easy solutions to the problems facing the US economy and its monetary policy guides today, they would have taken them.”

Why would they want to take those actions when they believe their current policies are successful?

CMA, When trying to reduce inflation, yes, it can run out of ammo.

Travis, I presume Bob agrees with this, he thinks monetary policy causes inflation. Arnold is the heterodox economist on that point.

CMA

Oct 19 2015 at 8:10pm

“4. A fiat money central bank never runs out of ammunition.”

“When trying to reduce inflation, yes, it can run out of ammo.”

Seems contradictory. Maybe in the first point you implied ammo to stimulate.

Its ammo can be ineffective too. The effects (NGDP) it wishes to generate may not occur if the tools are innefective. Trying to shoot someone 2km away with 9mm handguns may never work. You need sniper rifles.

ThomasH

Oct 20 2015 at 7:58am

Kling’s first comment is really embarrassing. The difference between a central bank trying to prevent a devaluation of it’s currency and to engineer one is fundamental. Multiple, frequent failures to prevent devaluations has almost no bearing on the ability to engineer a devaluation. Does anyone doubt the ability of China to devalue its currency? Zimbabwe?

Of course I am speaking of nominal devaluations, perhaps that is where some of the confusion among the commentators is.

Scott Sumner

Oct 20 2015 at 12:38pm

CMA, Yes, I meant ammo to stimulate, which is also what most other people are referring to when they discuss the possibility of the Fed running out of ammo.

I should have been clearer.

Comments are closed.