A recent FT article criticizes the view that we should try to eliminate the business cycle:

All this begs the question of whether longer really is better when it comes to business cycles. Recessions are a natural and normal part of capitalism, not something to be avoided at all costs. Indeed, the Deutsche Bank economists argue that productivity would be higher and American entrepreneurial zeal stronger if the US business cycle had not been artificially prolonged by monetary policy. . . .

Long periods of expansion invariably result in too much leverage, followed by a correction, and usually a recession. . . .

Maybe a tech productivity surge will eventually come along and turn this market-driven recovery cycle into something that spreads prosperity more widely. More likely there will be hell to pay for leaving the lights on too long.

I’m skeptical of this view. It’s not at all obvious why a period of too much borrowing needs to be followed by a period of high unemployment. If I borrowed too much I’d be inclined to work harder, not take a long vacation. A period of sharply rising unemployment is usually caused by sharp declines in NGDP growth, i.e. tight money, although bad supply-side policies may also cause unemployment.

The empirical studies I’ve seen suggest that long expansions do not store up trouble for the future, and indeed are no more likely to be followed by deep recessions than are short expansions.

Australia in now 28 years into their current expansion. Their central bank (the RBA) has a done a good job of maintaining adequate growth in NGDP. However, I do have some doubts about Philip Lowe, who has headed the RBA since 2016. Some of his remarks suggest that the RBA may be willing to tolerate a period of below target inflation as a way of preventing financial excesses. I view that as a mistake.

Australia has a 2% to 3% inflation target range, as part of a US-style dual mandate that also looks at employment. I certainly don’t favor slavishly targeting a given inflation figure, but I see no good reason for the recent undershoot of inflation in Australia.

Due to Lowe’s tight money policy, short-term interest rates have now fallen to 1.25% in Australia. As a result, the RBA may need to use unconventional monetary policy in the future. They were able to avoid using these policies during the Great Recession, and could have continued avoiding unconventional policies if they had kept inflation closer to 2.5%. The recent below target inflation is an unforced error in policy.

Stephen Kirchner has a paper that discusses how QE might be used in Australia if needed to prevent a recession. It is also one of the clearest explanations of market monetarist ideas that I have ever read. Here’s one example:

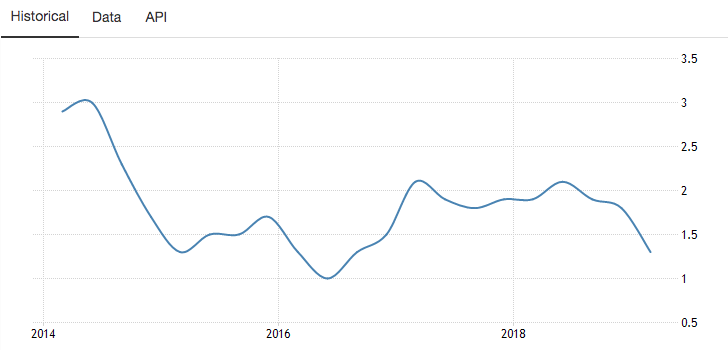

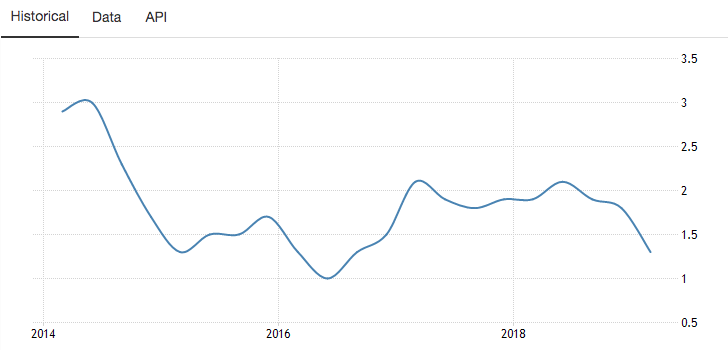

Confusion arises from the fact that long-term interest rates in the United States typically rose during QE episodes and declined during the intervening periods. Yields also rose in response to QE-related announcements.18 While QE is generally conceived to work through lowering long-term interest rates, that is only the static or liquidity effect. The dynamic effect is to raise expectations for long-term economic growth and inflation and this is also reflected in longer-term interest rates, which consistently rose during QE episodes and fell during the intervening periods (Figure 1).

Exactly. The purpose of QE is NOT to lower long-term interest rates. Rather the goal is to reduce interest rates relative to the equilibrium, or “natural” rate of interest. The main effect of QE is to raise the equilibrium rate of interest, not lower market rates.

Read the whole thing.

READER COMMENTS

JP

Jul 10 2019 at 6:41pm

QE’s aim is to raise future economic activity, which will raise interest rates via the income, inflation, and expected-inflation effects. As you always argue, interest rates are not the goal of monetary policy.

Benjamin Cole

Jul 10 2019 at 7:11pm

The FT article is another paean to tight money and the need for recessions. Oh, PU.

There is the germ of a good idea inside the FT article. I do think Western macroeconomistS need to figure out why leverage rises in business and economic expansions. The debt to GDP ratios get higher.

Is this because central banks must rely upon commercial banks to extend loans, to stimulate the economy? That is, central banks rely upon the commercial bank endogenous creation of money?

Would prudent, actually conservative, measure be to sidestep the commercial bank system, and for central banks to create money which they inject into the economy directly through money financed fiscal programs?

John Hall

Jul 11 2019 at 6:46am

That paper from Stephen Kirchner is really good. Thanks for sharing.

You also wrote: “It’s not at all obvious why a period of too much borrowing needs to be followed by a period of high unemployment. If I borrowed too much I’d be inclined to work harder, not take a long vacation. A period of sharply rising unemployment is usually caused by sharp declines in NGDP growth, i.e. tight money, although bad supply-side policies may also cause unemployment.”

My current thinking is that more leverage makes economies more susceptible to NGDP shocks, particularly negative ones. All else equal, the more highly levered a firm is, the riskier its equity and debt. If an economy is hit by an NGDP shock, then the highly levered firms will respond more to the shock. If the shock is bad enough, it could cause the equity to get wiped out and potentially cause losses to credit holders. If these highly levered firms are banks, then they will reduce or stop lending, which will make it more difficult for the central bank to implement monetary policy. This can exacerbate the previous NGDP shock.

Scott Sumner

Jul 11 2019 at 11:42am

John, It would certainly be wise to remove the tax bias, which favors debt over equity. This should be done even if debt is not destabilizing.

Mark

Jul 11 2019 at 8:04am

One thing that stands out about Australia is its very high rate of population growth—higher than virtually every developed country and even higher than many developing countries like India and Mexico: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_population_growth_rate.

Does this population growth make it easier to avoid recessions which are defined based on overall rather than per capita growth becoming negative, and/or warrant a lower inflation target to hit the same NGDP?

Scott Sumner

Jul 11 2019 at 11:44am

Yes, in the very indirect sense of making it less likely they’ll hit the zero bound.

It’s also possible that faster pop. growth reduces measured recessions, without reducing actual recessions. BTW, America had lots of recessions from 1948-61, and had fast pop. growth.

Alan Goldhammer

Jul 11 2019 at 8:11am

At times such as this one, it’s always good to go back and read Minsky’s classic book. While housing is not in the precarious state that it was back in 2005-06, there are a lot of dodgy loans to corporations with very weak balance sheets. The increasing tariff war(s) are leading to impacts on the economy that are not good. We have a Central Bank that seems more out of Eliot’s Prufrock poem than one grounded in economics.

“Stability leads to instability. The more stable things become and the longer things are stable, the more unstable they will be when the crisis hits.”

Keenan

Jul 11 2019 at 9:49am

I think an important point in regards to “too much borrowing” is that it is ok for persons/firms to die from too much borrowing. No recessions/sustaining expansions doesn’t mean that everything will be good for everyone forever.

Scott Sumner

Jul 11 2019 at 7:27pm

Yup. Too much borrowing may definitely be a problem. But the price should be buckling down and working harder, not unemployment.

LK Beland

Jul 12 2019 at 11:43am

Is leverage a problem for the US economy, compared to 2010? It really doesn’t look like it.

The US economy is (very) slightly less leveraged now than in 2010.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=ontn

Basically, households and financial corporations deleveraged, while nonfinancial corporations and the government increased their leverage. These effects almost perfectly balance out.

Also, the nonfinancial corporation leveraging was partly done to finance dividends and share buybacks without repatriating profits from tax heavens. It seems that they have reversed course in the past year, probably because of tax incentives to repatriate these profits, as well as interest rate increases.

robc

Jul 18 2019 at 11:39am

tax heavens

Nice typo.

Comments are closed.