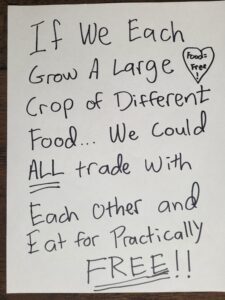

There is a photo of a restaurant whiteboard that has bumped around the interwebs for years. I first saw a version in April 2016, posted on Twitter by Scott Lincicome. Robert Tracinski offered some comments at the time, but the sentiment has now become a meme.

I have reproduced a version of the message here, written out in hippy-loopy longhand, the way this message should be written out. Here it is:

Those of us of a “certain age” remember the back-to-nature, self-sufficiency movement of the 1960s. There was a range of literature both celebrating and “how-to”-ing economic independence and moving “off the grid.” The most beloved source was probably “The Whole Earth Catalog,” which Steve Jobs famously compared to a paper version of “Google” in his 2005 Stanford commencement speech.

Now, being able to find information about how to do things on your own was, and is, a blessing. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the WEG ceased publication with the development of the internet. After all, the combination of Google and YouTube means that I can find a video that shows me how to do almost anything I could want to do. (Including “Grow Your Own Food!”)

That’s what makes the little whiteboard meme so interesting. Whoever first wrote it out recognizes that it makes no sense to “grow your own food.” Instead, what you need to do is grow a large quantity of a different crop, and trade for everything you don’t have. In other words, there are two states of world:

In State A I grow everything for myself, in small amounts. Say I have four acres, and I grow one acre of beans, one of corn, one of wheat, and one of tomatoes. The three other people in the world do the same thing. Overall, Person 1, Person 2, Person 3, and Person 4 each devote one acre each to each crop, so our little community has four acres of beans, four of corn, and the same for wheat and tomatoes. We are all self-sufficient! (If you remember the ‘Sixties, now is the time to hum “I am a Rock, I am an Island.”)

In State B I grow just one thing, on all of my four acres. Persons 2, 3, and 4 do the same. And then we exchange. You’ll immediately see that this means that the same total acreage is devoted to the same crops in both State A and State B: four acres of beans, of corn, of wheat, and of tomatoes. But whereas in State A each of us is self-sufficient, in State B we are mutually dependent.

So, there’s no difference, and we’d be better off in State A, where we don’t depend on anyone else, right? What’s so cool about the “free food” meme: the writer recognizes the error in this reasoning! We are actually better off in State B, perhaps by quite a bit, because of what Adam Smith taught us about Division of Labor.

But the memer doesn’t understand the principle that s/he was working with. Food is not free; it can’t be. If I grow one thing, the cost is whatever I didn’t grow. Further, if I eat something, it is not available for you to eat. So food always has a cost. The problem is how to get more, and better, and more various kinds of food, at lower prices, including costs to the environment.

The price of expecting others to give me food I lack is for me to give them food they lack, so that the exchange makes both of us, or all of us, better off. Famed George Mason University economist Walter Williams summarized Smith’s insight accurately: “The better I serve my fellow man…the greater my claim on the goods my fellow man produces. That’s the morality of the market.”

As Adam Smith put it:

So, the memer has a good idea: we’ll each grow a crop, and then trade. But it would be better still to have a commercial society, in which there is some commonly accepted measure of the value of the service we are providing one another in growing food to share.

Walter Williams extended Smith’s insight, in a way that makes clear why the system works so well:

Unsurprisingly, the system of money exchange that we have devised instead works better than the barter system of farming the romantic memer longs for. But that’s only because such people have never been near a barter system—or a farm, for that matter.

Michael Munger teaches at Duke University and is Director of the interdisciplinary program in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE) at Duke University. He is a frequent guest on EconTalk.

Read more of Michael Munger’s writing at Archive.

READER COMMENTS

Steve F.

Feb 20 2024 at 11:26am

Last summer, I had exactly this conversation with a bartender. I told her about a friend of mine who was a pediatric heart surgeon. I asked if she wanted him in the hospital, operating on babies, or home watering his corn. She said we could make an exception for people like him.

Then I asked about auto mechanics. Would she be OK hearing her car was going to be in the shop an extra day because the mechanic had to dig up his potatoes? No, that won’t be good.

Then I asked about her. Would I rather she was there, serving me beer, or trying to find someone who would take her peas in exchange for some beef?

The whole conversation lasted 5 – 10 minutes (I was the only one in the place). I hope she came away with a different viewpoint.

Dylan

Feb 20 2024 at 2:09pm

Is it a sign that I’ve hung out with free market folks too long that I thought that the sign writer was basically advocating for free markets? I mean, that’s what we basically do now except that not every single person has to grow food, some can design websites instead. And, we do eat for pretty darn close to free as the persistently declining share of household budget that goes to non-restaurant food shows.

Warren Platts

Feb 20 2024 at 5:06pm

Good article and a timely reminder that’s time to order seeds… Ugh.

Richard W. Fulmer

Feb 20 2024 at 6:12pm

In a free market system, someone with money in his pocket is someone who has served his fellow man but hasn’t yet received equal service in return.

Matthias

Feb 21 2024 at 11:00pm

Giving gifts, including gifting money is allowed.

You are right in spirit, though.

Btw even in an ‘impure’ system were some of the money is unearned, eg via government privilege, the whole system still works fairly well.

john hare

Feb 20 2024 at 6:52pm

I push back against the “practically free”. Growing things is work. And on small scale it is even more work.

MarkW

Feb 21 2024 at 5:48am

My response to the whiteboard would be something like — great idea! But what if I grow a lot of beans that I want to trade, but you don’t have any tomatoes that I want right now, but you still really need some of my beans? Maybe you could give me an IOU for tomatoes from the next harvest. But then imagine I find somebody else who has tomatoes ready earlier, so I trade some bean for those tomatoes and don’t need yours anymore. Is my IOU worthless? Maybe not — on my next barter deal, maybe I could give somebody your tomato IOU instead of beans! Oh, but wait, I just invented money and suddenly nothing is ‘free’ any more ;(

Matthias

Feb 21 2024 at 11:02pm

I agree with you in principle. And also see the white board as perhaps a stealth arguement in favour of free trade?

However, outside of a principled defense of the division of labour: some people just like tending to a small private garden and might get joy out of bartering with their neighbours.

Comments are closed.