I lost a good friend last March, Harry Watson, whom I had met at the University of Western Ontario in September 1971 and with whom I went to graduate school at UCLA, starting in September 1972. I’ve hesitated to write about him on EconLog because I’ve wanted to follow the overall rule to write about economics. But yesterday I was talking with a fellow UCLA graduate student, Tom Nagle, who had also been friends with Harry, and the stories that came up were all about economics.

So here goes.

At UWO, Harry and I were in a class taught by a Keynesian professor. I won’t name him because a few years ago I emailed him to ask if he remembered having said what Harry and I clearly remembered him saying, and he said he hadn’t. So I’ll call him Bob. Bob was a nice man. At the same time, he was totally sold on the Keynesian model. Harry Watson and I would often criticize the Keynesian model and propose Milton Friedman’s monetarism as an alternative. We were never nasty; hey, we were Canadian. But we were persistent. One time, Bob, frustrated at our objections, pointed to us and said to the class, “These guys are dangerous.” If you ever wanted to persuade people not to be outspoken, this was not the way to do it. I was 21 at the time and I suddenly felt taken seriously. Harry was 23 and I’m guessing he thought the same.

Every time Harry and I got together after that–and it was literally dozens of times–and there were other people around, he would tell that story and we would laugh uproariously. That’s one reason I remember it so well. It happened in the spring of 1972 and Harry started telling the story regularly from about 1976 on.

I also remember one area in which we disagreed with “Bob” a lot: Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis (PIH). It just made sense to us that people would base their consumption on some conception of their “permanent income” rather than on whatever their income happened to be at the time. But Bob presented empirical studies that purported to find evidence against the PIH. They were typically of cases where people got a windfall. If Friedman’s PIH was right, they would spend about 1/3 of it in the year they got the windfall. If Keynes was right, they would spend well over half of it. My recollection of some of the studies is, understandably, vague here because this happened over 51 years ago. But one study stands out. And it stands out because Harry Watson always made it part of his “routine” when he talked about our discussions in Bob’s class.

The study was about conscripts in Israel’s army getting out and being given a lump sum of about $200 (in early 1960s dollars, and it might have been less: it wasn’t more.) That’s not a small sum but it’s not a large amount either. Inflation adjusted by the CPI, it’s about $2,000 today.

Bob showed that the conscripts had spent almost all of it the first year. Harry challenged him, not on the data, but on the interpretation. “You’ve got guys getting out of the Israeli military, where they have been subject to a lot of discipline. They’re going to want to go out and drink and spend it on women,” said Harry. “This is not strong evidence against the PIH.”

That gets to something I noticed about Harry within 2 weeks of being in the same class with him: the perspective he brought to each issue, which seemed to be of someone way older than 23. I later learned why. His dad had married late in life and when Harry was born, his dad was 56. His dad, a successful businessman in Brantford, Ontario, had a number of male friends of approximately the same age. Many of them became Harry’s friends. I remember Harry telling me that at age 14 and 15, he had been a pallbearer at a number of their funerals. So he brought a wisdom to things that I had not seen in someone so young. It was from him, for example, that I first learned that there was an alternative view to the view I had adopted that population growth was bad. Harry pointed out that in poor countries, people needed to have a lot of kids because that was their version of Social Security. I had literally never thought of that.

I shared some of these reminiscences, plus others that didn’t have much to do with economics, at his memorial service in New Hampshire last month.

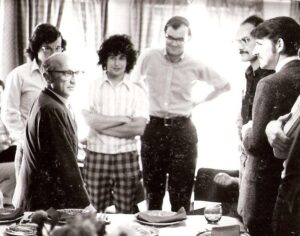

Note: In the above pic, taken at the first Austrian economics conference in South Royalton, Vermont, in June 1974, we were standing around talking to Milton Friedman in a polite but intense discussion. We had our intellectual differences with Milton too, but I don’t remember the issue. Behind Milton is Harry Watson. Then to our right with his arms crossed, his hair long, and a beautifully coordinated outfit is me, then Jerry O’Driscoll, then Jack High, and then Richard Ebeling.

READER COMMENTS

TMC

Aug 9 2023 at 8:47am

I’d also think the soldiers spending most of the money follows PIH as they expect their incomes to increase going into civilian life. They were expecting a pretty good pay increase, so started spending early. Also, this transition wasn’t cheap either. New clothing, places to live and furnish, etc. Transition from military life isn’t cheap – probably the very reason for the lump sum on the way out.

Comments are closed.