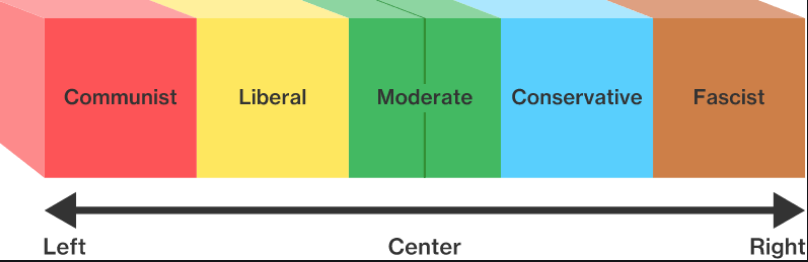

In recent years, the reporting at The Economist has moved somewhat to the left. Here’s a recent example:

But the assumption of rational self-interest constrains the welfare state significantly. Generous benefits, and the high taxes needed to fund them, will put rationally minded people off work, undermining economic growth and the government’s capacity to help people in need.

In practice, though, Mr Saez explained, the world works differently. . . .

Employment rates for prime-age men are remarkably similar across rich countries, Mr Saez pointed out, despite big differences in tax and welfare systems. Average tax rates in France are roughly 20 percentage points higher than those in America across the income distribution, yet about 80% of middle-aged men work in each country. (Americans do work more hours, but, as Mr Saez noted, this too reflects social choices, such as the shorter working week specified in French law.) There is strong social pressure for healthy men not to be seen as “freeloaders”, which pushes against the incentives created by higher taxes or bigger welfare cheques. Where social pressures to work are more ambiguous—as for the young or old or, in many places, women—generous benefits tend to have larger effects on employment decisions, Mr Saez noted. But this reinforces rather than undercuts the idea that social factors have important effects on economic decisions.

This isn’t exactly wrong, but it seems a bit misleading. The tone of the article is sort of dismissive of conservative arguments that the welfare state discourages work, but the actual empirical evidence suggests that it discourages work among the young, the old, women, and among men it leads to shorter work hours. This is one reason why per capita GDP (PPP) is far lower in Europe than in America. It’s not true that “the world works differently”; it works exactly the way that classical economic theory predicts. The European welfare state makes Europe a much poorer place. That may be fine (perhaps people prefer the extra leisure time), but it’s foolish to minimize the effect.

And to head off criticism, note that while some European welfare states have incomes well above the European average, so do some American states. Lots of things affect income, not just welfare and taxes.

Over the past quarter century, the center left has shifted a bit left on public policy issues:

1990s-style neoliberalism 2021 post-liberalism

1. Singapore style forced saving Expanded social insurance programs

2. Private infrastructure projects. Public infrastructure projects

3. Progressive consumption taxes Progressive income/wealth taxes

4. Fiscal responsibility Deficits don’t matter

5. Monetary stabilization policy Fiscal stabilization policy

6. Low wage subsidies Higher minimum wages

7. Privatization More aggressive antitrust

In 1996, Clinton ran for re-election on ideas such as “the era of big government is over” and “ending welfare as we know it.” Fiscal stabilization policy was a complete non-starter. We were moving toward budget surpluses, with an eye on the demographic time bomb created by lower birth rates and longer life expectancy.

Why the recent move toward a slightly more socialist approach to policy? (Yes, it’s far from outright socialism, but for the most part the list above is not a move toward the Nordic model, at least the post-1990 Nordic model.)

Some might quote Keynes’s famous remark about how to respond to new information, but I’m not convinced that this can explain the shift. I’m only an expert on one of the 7 areas above (stabilization policy), but in that one area I’ve seen a lots of bad arguments for the move toward fiscal policy, arguments that reflect a misunderstanding of macro theory and an ignorance of macroeconomic history. So I have little confidence that the other 6 examples are any better justified. Especially when I see dubious claims that a less effective policy (minimum wages) can be justified on the basis of being more politically acceptable than a more effective policy (low wage subsidies). We have an EITC program! And we have a new government where the Democrats have an easier time with new spending programs (requiring 50 senators) than regulatory changes (requiring 60 senators).

So what explains the shift? I suspect it’s a mix of various factors. Monetary policy failures like the Great Depression and the Great Recession are almost always misdiagnosed as a failure of capitalism. The move toward an information economy has made income less equal. The zero lower bound makes monetary policy seem less effective than it is.

More speculatively, the center right might feel increasingly comfortable viewing the center left as their “tribe”. The days of P.J. O’Rourke’s “Republican Party Reptile” is long gone. It’s no longer cool to be associated with an ideology that has become increasingly nationalistic and anti-intellectual. Meanwhile, the demise of communism has removed some of the taint from the left. Media outlets such as The Economist and the Financial Times, and think tanks like the Niskanen Center, seem increasingly at home in the center left.

PS. I used the term “post-liberal”, as its relationship to liberalism is analogous to the relationship of post-Keynesian to Keynesianism. Similarly, modernism was followed by postmodernism. In any case, neoliberalism is already taken, and neo-neoliberalism just sounds stupid.

READER COMMENTS

Mark Z

Jan 24 2021 at 4:24pm

Doesn’t the very existence of the income inequality Saez et al. want higher taxes to combat kind of belie their position that ‘social factors’ matter more than financial ones? For that to be true, either workers care more about pre-tax than post-tax income (they care how big of a number their employers put on their paychecks but not so much how much the state lets them keep) or most employers are cluelessly paying their most skilled employees way more than necessary, but it somehow hasn’t occurred to them that they could dramatically cut their engineers’ and lawyers’ salaries without them leaving to other firms.

Thomas Hutcheson

Jan 24 2021 at 4:38pm

True, but I think what’s behind that is the increasingly farther Right prevented the realization of any of the left column aspirations and led the center right to move left in an attempt to achieve “second best” results.

How much time do most people on this site spend arguing for carbon taxes, shifting health insurance from firm “provided” to subsidized individual purchase, progressive consumption taxes, a higher EITC, multilateral trade liberalization, or for the Fed to actually hit its targets?

Jose Pablo

Jan 24 2021 at 6:08pm

You hit the nail on the head!!

I was actually unable to finish reading this article in The Economist. And being unable to finish an article at The Economist, or feeling a strong disagreement after finishing it, is, actually, happening to me at an increasing rate lately (last 3-4 months, maybe more).

Since I suffer from a very strong confirmation bias, I think this clearly proves your point that the Economist is moving to the left.

Are you aware of any change behind this shifting?

Scott Sumner

Jan 24 2021 at 11:13pm

I think the FT has also moved a bit leftward. Probably many other media outlets as well. I believe that polls show the economics profession also moving a bit to the left.

Mark Z

Jan 25 2021 at 4:17pm

I agree. When I was in college (not an incredibly long time ago) the FT was seen as a quintessentially neoliberal paper. Sometime last year I read a news article – not an oped – in the FT on healthcare in the US that seemed almost overtly supportive of socializing healthcare, using if I remember correctly people in the Sanders presidential campaign as its main ‘objective source.’ I sort of chalked it up the it being a British newspaper and socialized healthcare being more or less a valence issue there, but there does seem to be a shift there, or maybe it’s just I’ve moved rightward since college.

Dylan

Jan 25 2021 at 5:38pm

Is that really that new? One of my first recollections of reading The Economist was around ’92 when they were fairly supportive of Paul Tsongas’ healthcare plan. And in my reading in later years that didn’t seem like a one off. Thought they’ve been consistently in favor of some form of universal coverage with market based mechanisms built in?

I don’t have nearly as long of a history with the FT, only been reading it regularly for a couple of years, but they too seem to be in that center-left category for the U.S., which means center-right in Europe?

Scott Sumner

Jan 25 2021 at 6:02pm

Of course Mitt Romney produced the first version of Obamacare.

Rajat

Jan 24 2021 at 6:26pm

This resonates with me. Not that I’m an intellectual in any meaningful sense, but thinking of myself a classical liberal, I wouldn’t say I “feel increasingly comfortable viewing the center left as [my] tribe”. I find it exceedingly uncomfortable, but at least there’s something of rational debate to be had there on certain issues.

Obviously, this means – as always – one should read a variety of opinions. But given the diminishing presence and status of classical liberal public intellectuals (at least on the internet), can you recommend contemporary classical liberals who write on the above policy areas? I’m pretty familiar those who write on antritrust (eg Geoff Manne and others at ICLE, and Josh Wright and others at George Mason’s GAI), but what about in other areas?

Rajat

Jan 25 2021 at 12:30am

Oops, I don’t know what happened, but my comment disappeared. I don’t think it breached any policies. I was asking if you could recommend any classical liberal writers covering the above policy topics (apart from antitrust, where I follow quite a few).

Scott Sumner

Jan 25 2021 at 12:34pm

Someone with a better memory for names can answer this, but Mercatus, Cato, Hoover and other similar institutions produce good research on classical liberalism.

BC

Jan 25 2021 at 4:13am

It would be interesting to compare “2021 post-liberalism” with 1970s style liberalism (or pre-neoliberalism). I don’t get the impression that they are very much different. If the proponents of 2021 post-liberalism won’t clearly differentiate themselves from failed and discredited 1970s-era liberalism, then why should we believe that repeating the same policies won’t lead to the same failures this time around? More apropos than Keynes’s remark about new information would be Santayana’s admonition about forgetting the mistakes of the past and Einstein’s definition* of insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

*Apparently, it’s disputed as to whether the insanity quote should be attributed to Einstein.

Scott Sumner

Jan 25 2021 at 12:30pm

BC, One difference is that 1970s liberals favored price controls and “incomes policies” (i.e. maximum wages.) Now they want minimum wages.

Procrustes

Jan 25 2021 at 6:22am

I quite agree on the Economist’s leftward drift. For example their articles on minimum wages over the last five or so years extol the findings of pro minimum wage research while downplaying both simple logic (when the price of something rises people tend to want less of it) and the lack of reality of the fancy pants economics that seems to find monopsony everywhere especially in the restaurant trade that means businesses can magick up transfers of super profits.

Scott Sumner

Jan 25 2021 at 12:32pm

Good point.

Pierre Lemieux

Jan 25 2021 at 10:48am

Interesting questions, Scott. There is something off, though, in your parenthetical and partly rhetorical question: “perhaps people prefer the extra leisure time.” Adding rational ignorance and agenda control (and a few other bits and pieces) to Arrow’s theorem, I suggest this should be reformulated as “perhaps some incoherent majority or minority votes or pushes for more leisure time for some people.”

Scott Sumner

Jan 25 2021 at 12:32pm

That’s closer to my view, but I made the comment to emphasize that I was making a positive point, not a normative one.

Craig

Jan 25 2021 at 8:48pm

I’ve worked in many contexts with European colleagues where the work/leisure indifference curve between individuals becomes very visible. My anecdotal experience is Americans will blow out the clock and the Europeans just have some kind of mental limit on it. The Europeans were always on time and not lazy so I don’t think its a straight up preference for leisure. I think there must be side hustles and DIY/meal prep, etc involved.

I’ll trade work $ for meals any day. Pre-pandemic, leave the office, pick something up, eat it at home. My working hypothesis here is that the Europeans sense when they are in Europe that they are being jammed into marginally higher brakcets and so, they’d rather just get food from the grocery store and make it at home. And then I wonder how many are putting in the ‘minimum required’ at work just to get the hell out of there because their side hustle, which might not sustain them full time, is better on the margin than working 40+

Kind’ve sort’ve like the Soviet farm where the Soviet farmers would have to put some time into the collective farm but would really spend alot of their time on their private plot.

Henri Hein

Jan 25 2021 at 12:54pm

I had also noticed a left-ward shift at some of my favorite magazines, including The Economist. At a personal level, it can be hard to tell whether the source in question is really moving left, or I myself am changing my views, so it helps to see someone like you pointing it out with specifics.

About disincentives generated by high income tax levels, I read that though men tend to work similar hours even with a high tax rate, they also tend to start work later in life and retire earlier. So measured over a lifetime, there is a disincentive effect. I can’t find it right now, but here is an interesting list of retirement ages in different countries.

sean

Jan 25 2021 at 3:10pm

Some of the change in rational. Carville is famous for saying when he comes back in another life he wants to be a bond trader – they intimidate everyone. Back in Clinton’s days the bond market was a real limiting factor on increased spending. Its not today.

I attribute a lot of the weak bond market influence on policy to wealth inequality itself. Surplus financial savings and the rich getting rich thru lower taxes has led to surplus savings. I have a feeling in a world of higher taxes the bond market wouldn’t be as friendly. The truth is the rich of today can’t consume close to their wealth so it ends up in financial assets.

You should check out reddit’s neoliberalism. They are probably what you refer to as post-liberalism but instead claim old neoliberalism as their own. Redefining the word.

nobody.really

Jan 28 2021 at 11:48am

I don’t know that Boutros Boutros-Ghali would agree.

Thomas Strenge

Jan 28 2021 at 1:10pm

It’s kind of you to say that The Economist shifted leftward recently. I think the shift became obvious when The Economist endorsed Obama. The Left, claiming to be the party of science, has abandoned economics, history, and biology all in the name of power. I have no doubt that Chemistry and Physics will be next if they prove politically inconvenient.

Comments are closed.