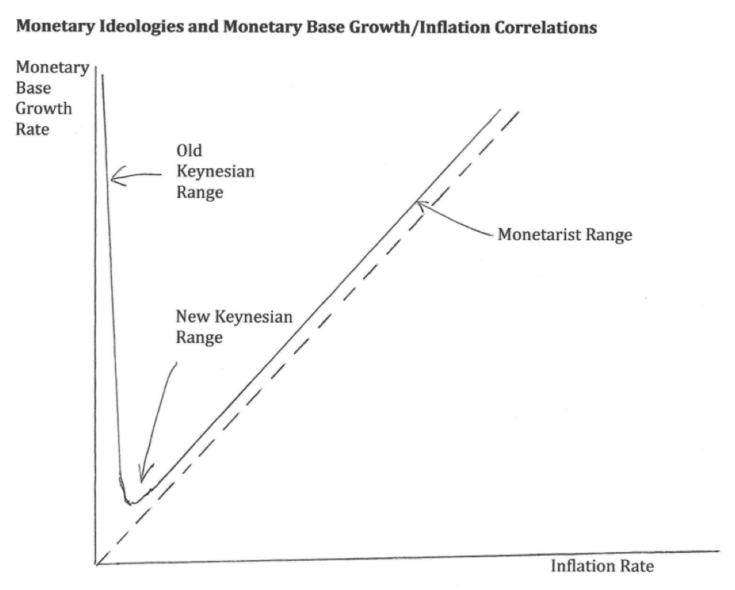

I have a new article in Economic Affairs, which discusses the prospects for monetarism in the 21st century. Unfortunately, the journal was not able to use my graphs, therefore I’d like to discuss one omitted graph that illustrates an interesting trait of macroeconomics—it’s lack of fixed principles. There is a tendency of macroeconomists to shift with the intellectual fashions of the day.

In the paper, I discussed three general approaches to monetary economics.

1. Old Keynesianism: Money supply data uninformative and monetary policy is often ineffective.

2. New Keynesian: Money supply data is uninformative and monetary policy is highly effective.

3. Monetarism: Money supply data is informative and monetary policy is highly effective.

Old Keynesianism is popular when inflation is so low that nominal interest rates fall close to zero. In that environment, one often sees large increases in the monetary base coinciding with very low inflation (left portion of the graph). This leads many to assume that monetary policy is ineffective at the zero lower bound. Monetarism is least popular during these periods. Keynes’s General Theory was actually a special theory for an economy with near zero inflation expectations.

New Keynesianism is most popular when inflation is at moderate levels and fairly stable, say from 1983 to 2007. During these periods, there is little correlation between money growth and inflation, mostly because inflation is quite stable. It’s not that money doesn’t matter, rather it’s an example of what Milton Friedman called the thermostat problem. If you skillfully adjust a thermostat to keep the temperature at a constant 72 degrees, it looks like the thermostat is not influencing the temperature. New Keynesians do regard monetary policy as still being highly effective, but they focus on interest rates, not the money supply.

Monetarism is most popular during periods of high and unstable inflation, such as the 1970s. During those periods, there is usually a close correlation between long run money growth rates and inflation (right portion of the graph). In contrast, interest rates become an unreliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy due to the Fisher effect.

Personally, I view it as a major embarrassment that macroeconomists shift between these models according to the inflation trends of the moment—like teenagers changing their style of dress each fall. We need a monetary model that fits any macroeconomic environment. My preference is market monetarism, where NGDP futures are both the indicator and instrument of monetary policy. Where monetary policy is always effective and fiscal stabilization policy is never needed.

I am currently working on a book that will make the case for a truly “general theory”, a monetary theory that explains monetary policy in both Japan and Zimbabwe.

READER COMMENTS

John Hall

Jul 11 2022 at 3:30pm

“Personably, I view it as a major embarrassment that macroeconomists shift between these models according to the inflation trends of the moment—like teenagers changing their style of dress each fall. We need a monetary model that fits any macroeconomic environment. My preference is market monetarism, where NGDP futures are both the indicator and instrument of monetary policy. Where monetary policy is always effective and fiscal stabilization policy is never needed.”

A macroeconomic model with NGDP futures as an instrument of monetary is a special theory as well. A general theory would allow incorporating any number of the popular monetary policy instruments and then show what the resulting key economic variables would do in a way that more-or-less matches with reality.

Jose Pablo

Jul 11 2022 at 5:00pm

“Personably, I view it as a major embarrassment that macroeconomists shift between these models according to the inflation trends of the moment”

That’s an understatement. Particularly if we pretend to claim that macroeconomy is a science

“a monetary theory that explains monetary policy in both Japan and Zimbabwe.”

I can’t way!!

This very interesting monetary theory of yours, would also allow to predict the future?

Jose Pablo

Jul 11 2022 at 5:01pm

‘* I can’t wait!!

Scott Sumner

Jul 12 2022 at 12:36pm

“would also allow to predict the future?”

See my reply to James.

James

Jul 12 2022 at 1:06am

Scott,

I see many economists talk about their models as if they can be used to predict the consequences of central bank actions. I also see basically none of these economists use their models to make public predictions about the variables people care about (output, unemployment, inflation) based on variables the central bank controls (fed funds target, money supply, whatever else is in the model).

Do you believe you have a model that makes it possible to predict the consequences of central bank actions? Are your forecast errors smaller than some sort of baseline such as simple exponential smoothing? If so, you really ought to start publishing the forecasts of your models on a regular basis.

Please do not say that you do not publish forecasts because you prefer market forecasts. We all know futures prices are better forecasts than economists’ estimates. If you are in the business of building models, you would only increase your credibility by showing that your models generate better forecasts than the alternative models that other economists favor.

Scott Sumner

Jul 12 2022 at 12:34pm

“Please do not say that you do not publish forecasts because you prefer market forecasts. We all know futures prices are better forecasts than economists’ estimates. If you are in the business of building models, you would only increase your credibility by showing that your models generate better forecasts than the alternative models that other economists favor.”

I don’t believe you understand the purpose of macroeconomic models. The purpose is not to forecast macro variables (futures markets already do that better than economists can), it’s to prevent monetary shocks from destabilizing the economy.

If you want a conditional prediction, here it is: Stabilizing expected growth in NGDP would reduce the volatility of the business cycle. That’s the prediction of my model.

Just as what a child wants to eat is not always what’s best for them, what the public wants from economists is not what the public needs from economists.

“I also see basically none of these economists use their models to make public predictions about the variables people care about (output, unemployment, inflation) based on variables the central bank controls (fed funds target, money supply, whatever else is in the model).”

Take another look at my graph. Do you see the point? What prediction would you make if told the money supply will grow rapidly? Is that what the graph says?

James

Jul 13 2022 at 5:16pm

Say I am a central banker and I am considering a change in the fed funds target rate change of either 0 or 25 or -25 bps. I need to estimate forward unemployment and inflation under all scenarios in order to make the decision.

Futures markets give very good unconditional expectations but I need forecasts conditional on my decision.

How can your model help me if it does not offer conditional forecasts?

As it renders on my screen, your graph has no numbered tick marks on the axes.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2022 at 8:38pm

The graph has nothing to do with determining where to set interest rates. My point is that the money supply (and by implication interest rates) do not provide a reliable indication of the stance of monetary policy.

I have a Mercatus paper discussing how to use futures markets to make conditional forecasts. When the market forecast is on target, then the market has implicitly forecast the instrument setting that leads to an on-target level of aggregate demand.

Think about the Bretton Woods regime. The market basically forecast the interest rate setting (and money supply) that would lead to the exchange rate being equal to the official pegged rate. We know that countries are able to maintain fixed exchange rates for decades on end if they choose to, so the instrument setting issue is obviously solvable.

Michael Rulle

Jul 12 2022 at 9:04am

Jackson Browne on Macroeconomics (from “Cocaine”)

“Gotta take either more of it or less of it. I can’t quite figure out which one. Well, I tell ya what it does take. It takes a clear mind is what it takes. You mean it takes a clear mind to take it or a clear mind not to take it?It takes a clear mind to make it. ”

Spencer Bradley Hall

Jul 12 2022 at 9:12am

You can’t model an economy without metrics. And the metrics the FED uses are contaminated and keep changing (getting worse). The FED desperately needs audited.

The Fed – Understanding Bank Deposit Growth during the COVID-19 Pandemic (federalreserve.gov)

“Whether deposits stay in the banking system depends on the behavior of the firms and households who received those deposits. Newly created deposits might stay within the banking system if they are used to purchase something else—either a consumption good, an investment good, or a security—which ultimately results in the deposits being sent to the bank accounts of households, businesses, or nonbank financial institutions at the other side of the purchase transaction. On the other hand, the deposits may leave the banking system if the holder of the deposits exchanges them for a different bank liability, such as longer-term bank debt, or if the deposits are used either to buy shares in a money market mutual fund, which then uses those deposits to buy alternative bank liabilities or Treasury securities directly from the U.S. Treasury department, or to invest them in the Federal Reserve’s Overnight Reverse Repurchase (ON RRP) facility.”

But the FED doesn’t separate and record bank vs. nonbank purchases from the FRB-NY’s trading desk. Thus, the money stock is greatly distorted.

marcus nunes

Jul 12 2022 at 3:25pm

“It’s not that money doesn’t matter, rather it’s an example of what Milton Friedman called the thermostat problem.”

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/misleading-monetarist-views

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jul 12 2022 at 4:22pm

Please include in the book how the optimal NGDP target is to be chosen (or at least the arguments of the function) and under what circumstances the Fed would deviate from it?

James

Jul 13 2022 at 5:28pm

Scott, I think I do not understand your view of financial markets. Forget NGDP futures for a moment. Say I am an executive at a car company and I am considering a change in the number of cars we manufacture each year, but I have not announced anything yet. In your view, can I look at the share price of my company to determine whether profit will be higher or lower after this change?

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2022 at 8:31pm

No.

Edwin Alvarenga

Jul 25 2022 at 4:00pm

You would think monetarism would be popular in today’s environment, but it’s still being completely ignored. Krugman didn’t even mention monetary policy once in his new “I Was Wrong About Inflation” article.

Comments are closed.